Copy of Declaration of Independence, Hidden Behind Wall Paper During the Civil War, Resurfaces in Texas

The document, which belonged to James Madison, is one of 200 facsimiles commissioned in the 19th century

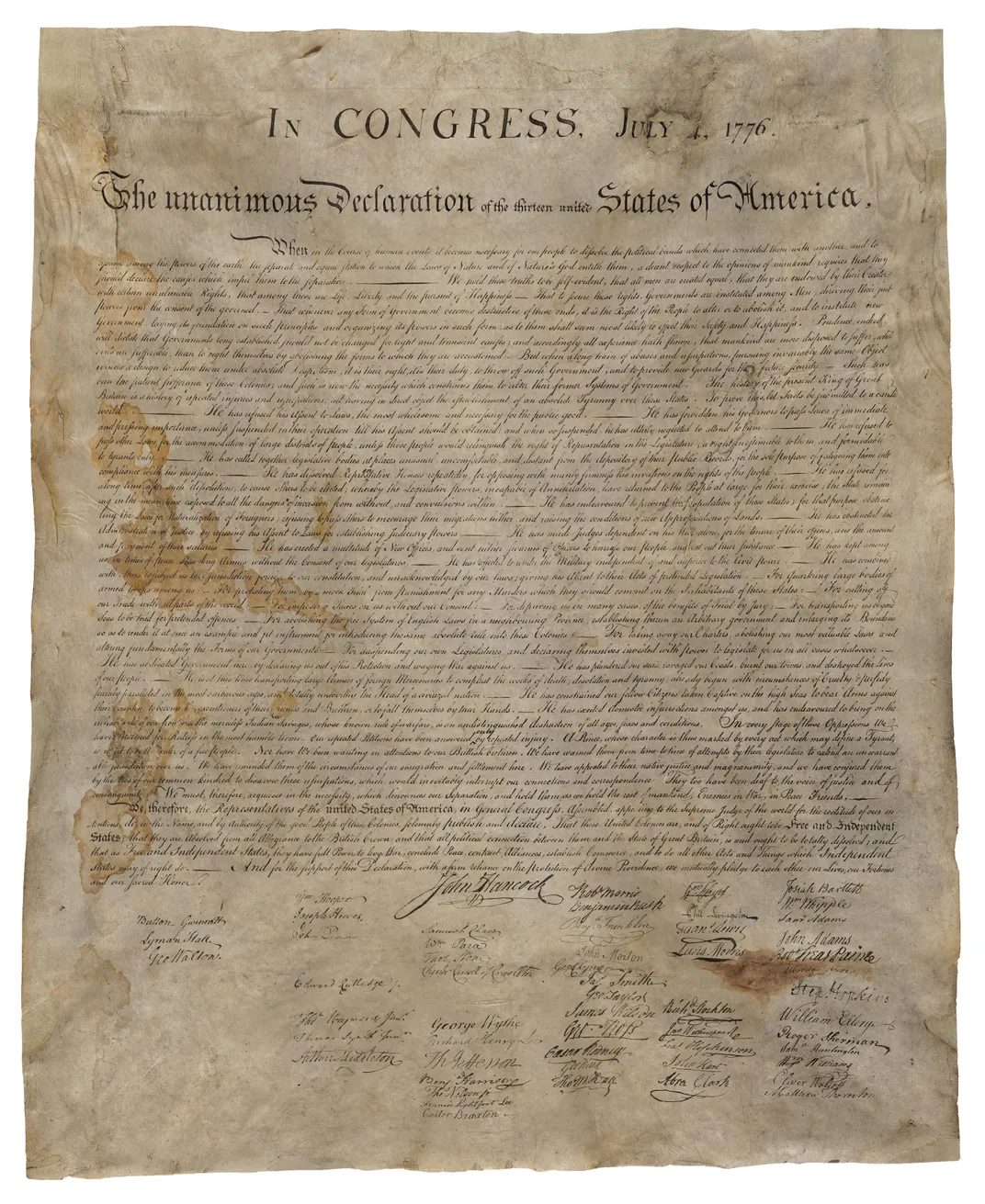

Within 40 years of its signing in 1776, the Declaration of Independence was starting to show signs of aging and wear. So in 1820, John Quincy Adams commissioned printer William Stone to make 200 facsimiles of the precious document. As Michael E. Ruane reports for the Washington Post, one of these meticulous copies, long believed to have been lost, recently resurfaced in Texas.

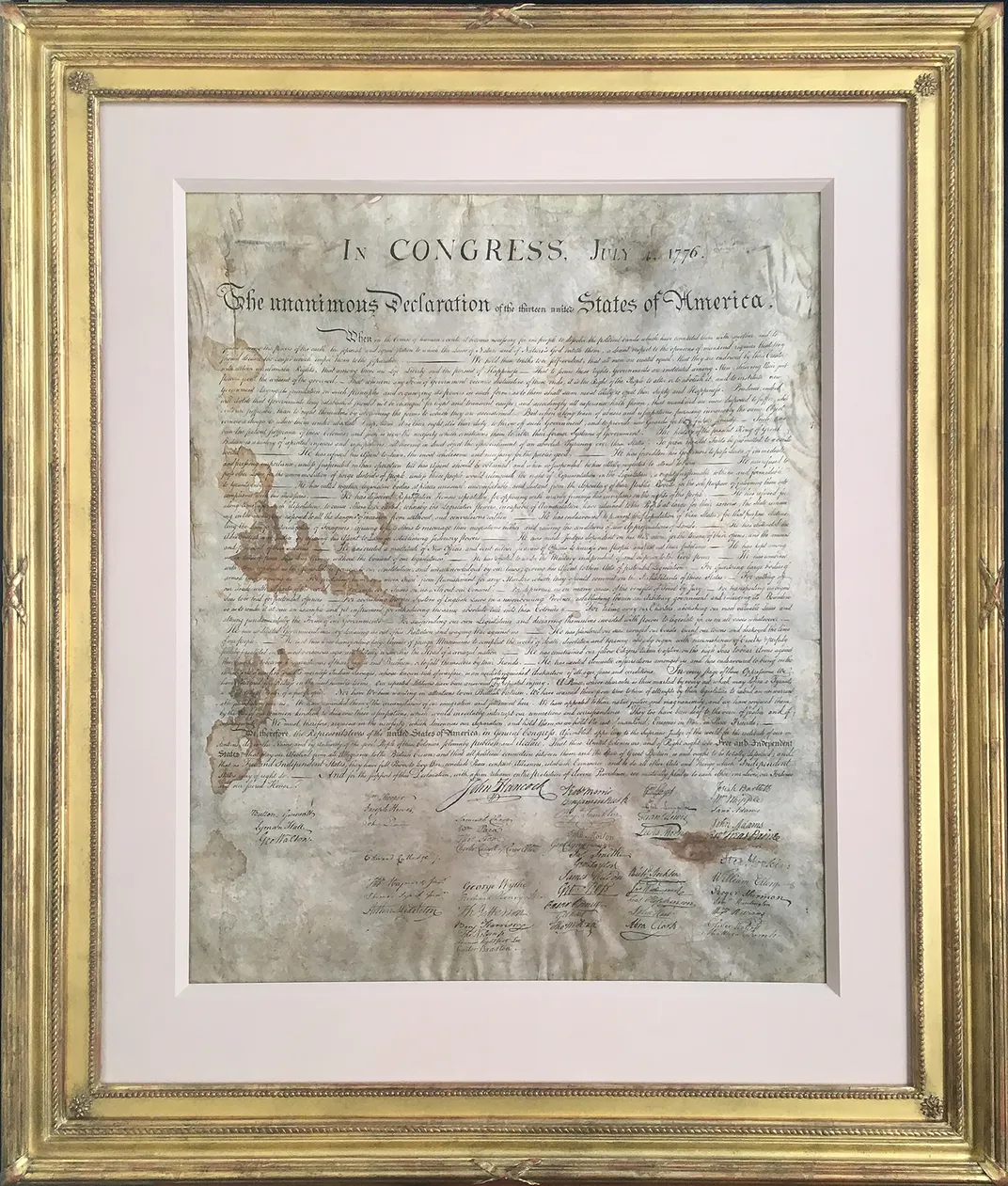

Over the past two centuries, the document had been owned by James Madison, hidden behind wallpaper during the Civil War, and ultimately stored in a bedroom closet. The copy was recently purchased by the philanthropist David M. Rubenstein.

The original copy of the Declaration, which is stored at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., was etched into calfskin and signed by 56 delegates. According to the website of Seth Kaller, the rare document appraiser who facilitated the recent sale, the Declaration “was frequently unrolled for display to visitors, and the signatures, especially, began to fade after nearly fifty years of handling.” Worried about the posterity of the document, Adams turned to Stone.

To make his replica, Stone spent three years engraving an exacting copy of the original document onto a copper plate. Once the 200 facsimiles were printed, they were distributed to Congress, the White House and various political figures. Former president James Madison received two copies.

For many years, Kaller tells Ruane, experts had “no idea that [this copy] had survived.” But it had, in fact, been held for generations by the family of one Michael O’Mara of Houston, Texas, who rediscovered the document while going through family papers after his mother’s death in 2014. His family had once displayed Madison’s copy on their mantelpiece, but came to believe that the document was “worthless” and transferred it to a bedroom closet, O’Mara tells Ruane.

The Declaration copy had been given to O’Mara’s mother, who is a descendant of Robert Lewis Madison, James Madison’s favorite nephew. It is believed that Robert Madison received the copy from his uncle. The document subsequently passed into the hands of Robert Madison’s son, Col. Robert Lewis Madison Jr., who served as a doctor for the Confederate army during the Civil War.

According to a 1913 newspaper article that O’Mara found amid his family’s papers, Madison Jr.’s wife decided to hide the Declaration copy behind the wallpaper of the family’s home during the heat of the conflict, fearing that it might fall into the hands of Union soldiers.

O’Mara's research brought him to Rubenstein, who owns four other William Stone facsimiles. Stone’s work is particularly prized because, as Kaller’s website notes, his engraving “is the best representation of the Declaration as the manuscript looked prior to its nearly complete deterioration.”

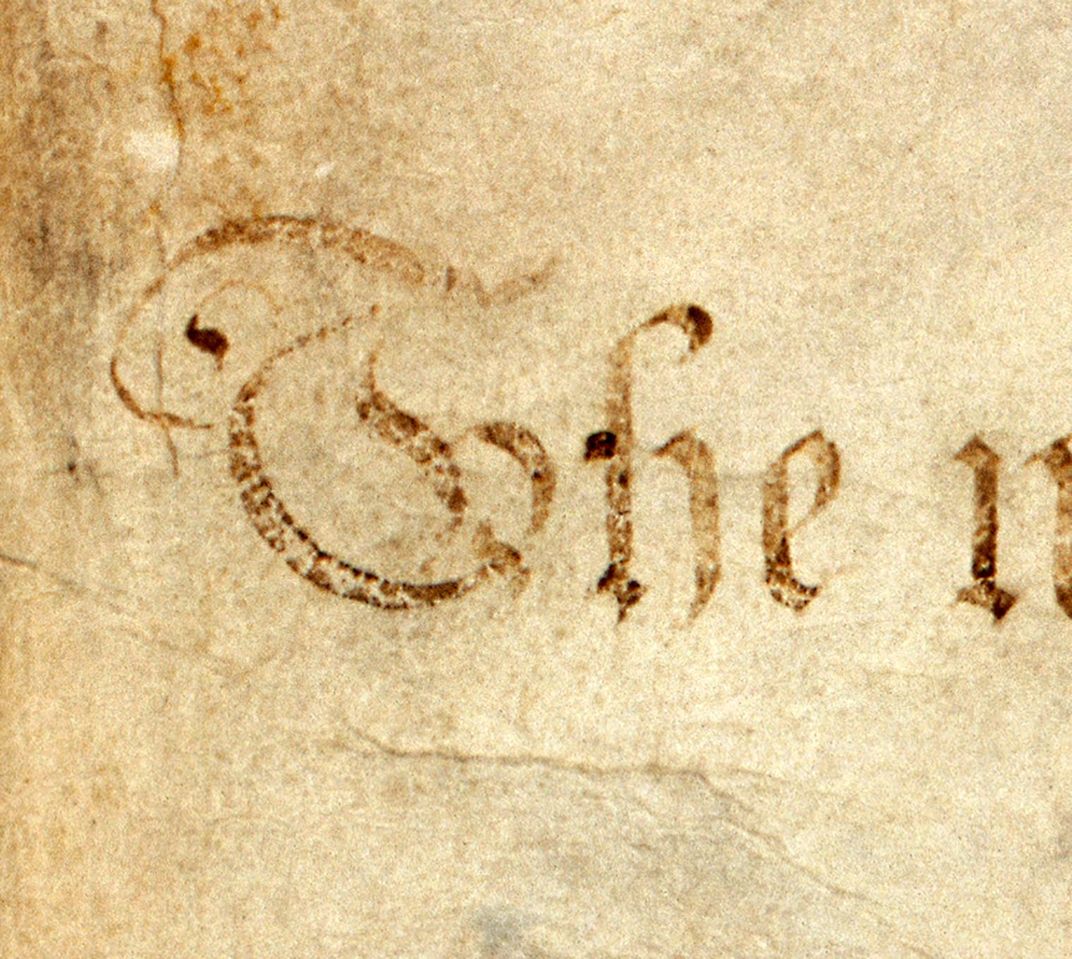

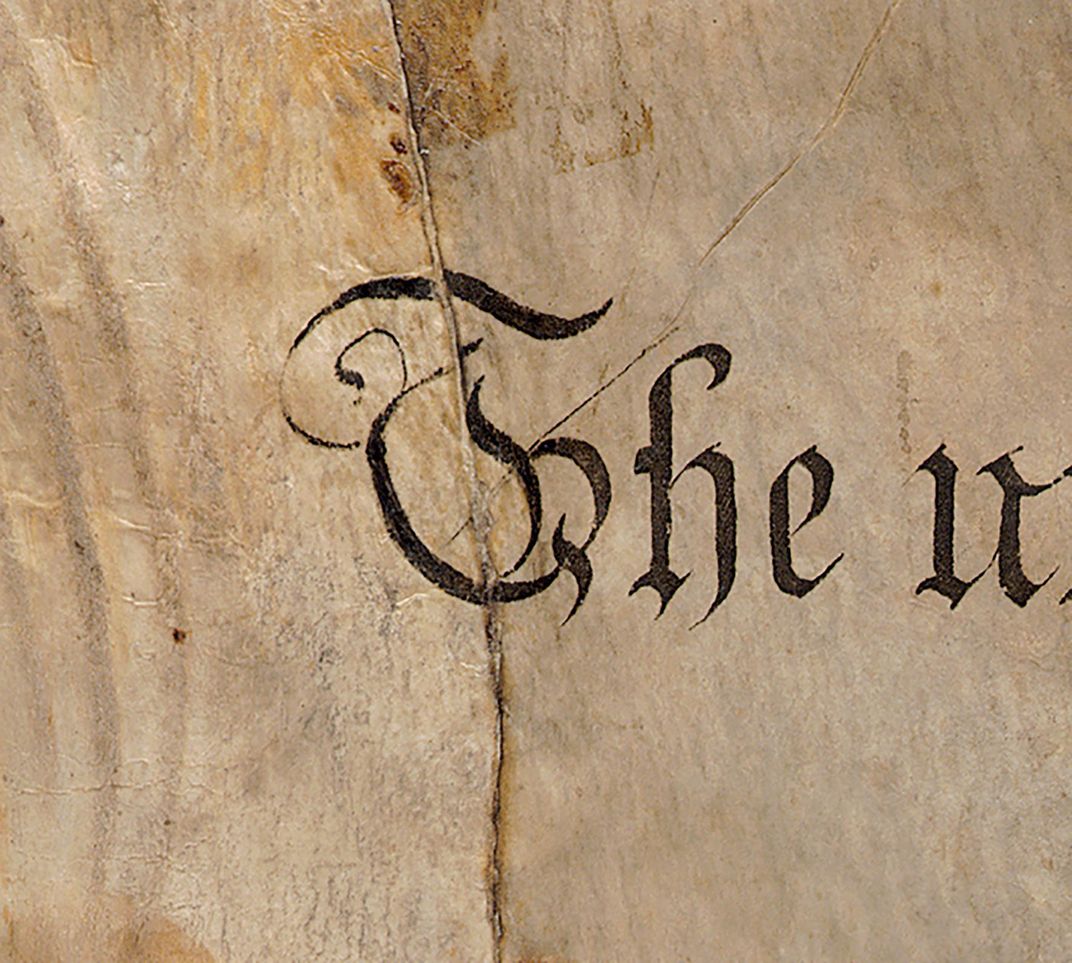

The newly discovered copy is, however, notable for the way that its first letter is embelleshed. The document's "T," which begins "The unanimous Declaration ..." slightly deviates from the original Declaration's flourished "T," and includes a decorative diagonal line running through it.

After the Stone copy was authenticated, conservationists spent about ten months stabilizing the document, which had suffered moisture damage due to its less-than-conventional storing methods. Rubenstein, who agreed to purchase it for an undisclosed price, tells Ruane that he plans to lend out the newly discovered copy for display; the first institution to receive it will be the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

"These relics were produced with the idea that they would be cherished as iconic images, but it's funny because for more than a century they really weren't recognized as such," Kaller tells Smithsonian.com. "There was no market for them and no easy way to display them, and so they largely got forgotten. It's amazing that this was preserved and now discovered."