David Goldblatt, the South African Photographer Who Documented Life Under Apartheid, Has Died at 87

He did not rush to the frontlines of violent events, but instead photographed everyday scenes of racial discrimination

David Goldblatt, the renowned South African photographer who captured evocative, often heartbreaking scenes from his native country’s apartheid regime, has died at the age of 87.

Neil Genzlinger of the New York Times reports that the cause of death was cancer.

“A legend, a teacher, a national icon, and a man of absolute integrity has passed,” Liza Essers, director of South Africa’s Goodman Gallery, which represented the photographer for many years and will now represent his estate, said in a statement.

Goldblatt was born in a small mining town near Johannesburg in 1930. As M. Neelika Jayawardane explains in Al Jazeera, Goldblatt came of age during the rise of the National Party; when it came to power in 1948, the party began implementing apartheid policies that systematically marginalized non-white South Africans.

Against this tumultuous political backdrop, the young Goldblatt developed an interest in photography-focused magazines like Life, Look, and Picture Post. “In the early 1950s, I tried to become a magazine photographer,” he told the British Journal of Photography in 2013. “I sent my pictures to Picture Post and got rejected. Then, when the African National Congress became active in their struggle against apartheid, Tom Hopkinson, the editor of Picture Post, contacted me and asked if I could make something. So I went to an ANC meeting and photographed everything I saw.”

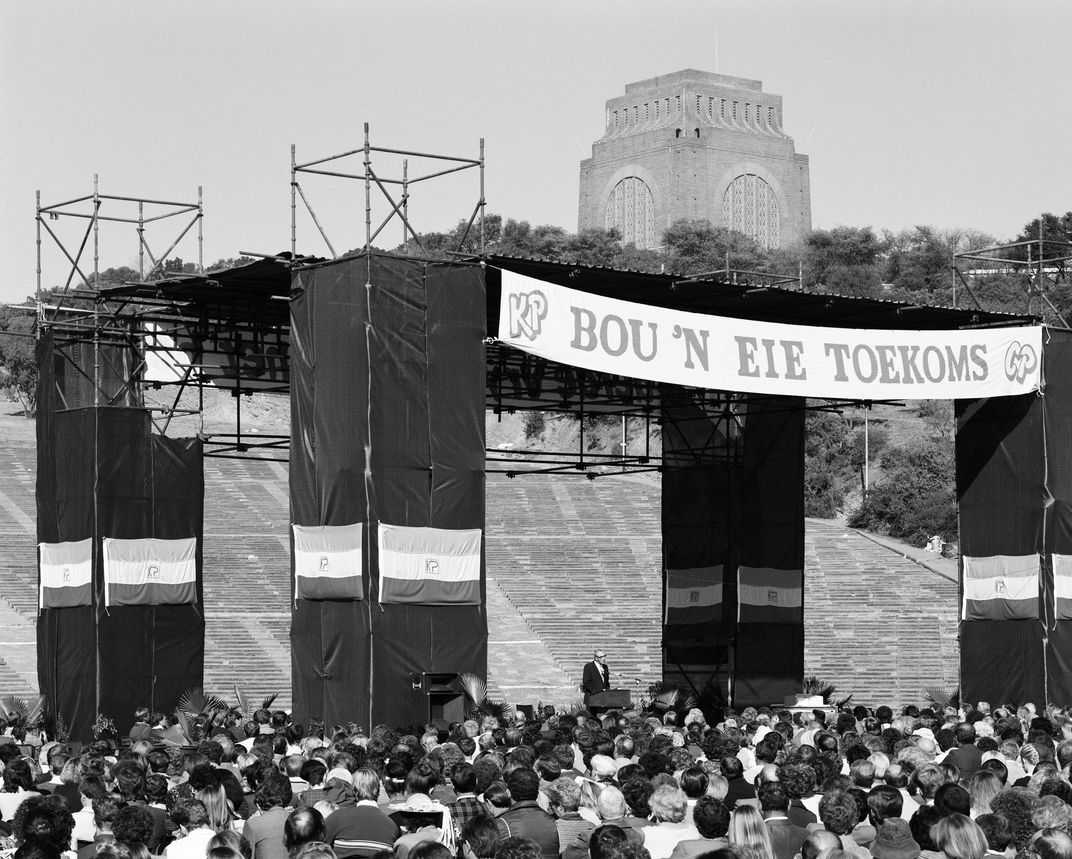

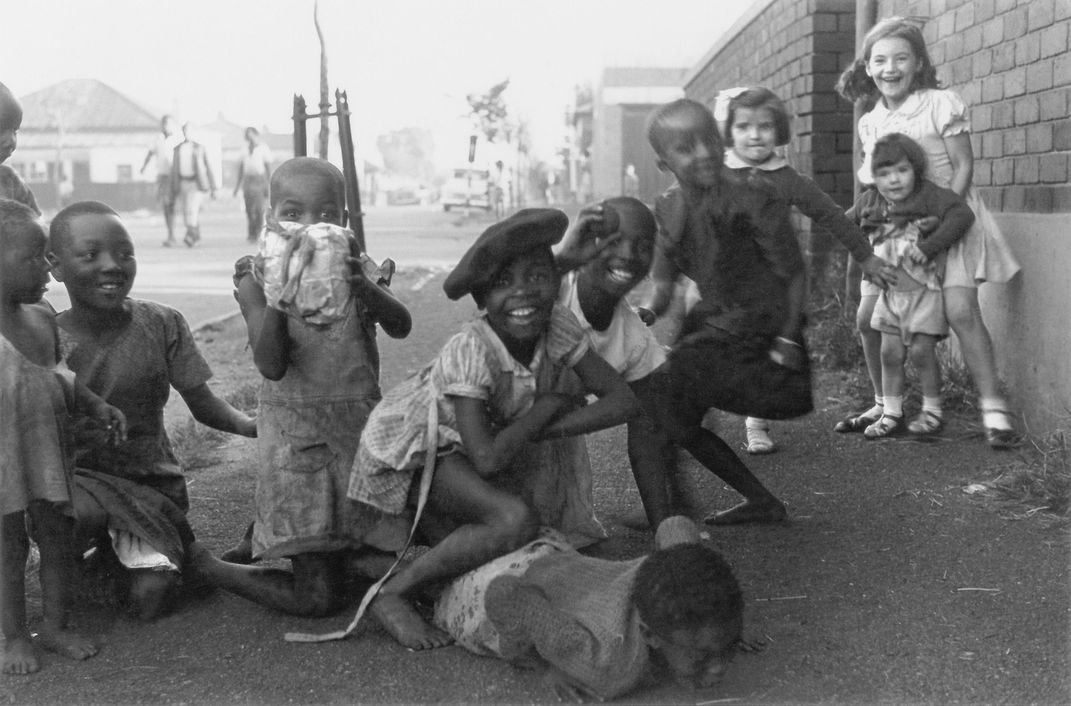

When Goldblatt first embarked on his career as a photographer, he wanted to show the world the injustices of the apartheid regime. But he did not rush to the frontlines of rallies or violent events. “I’m a coward, I run away from violence,” Goldblatt told ASX in 2013. “And I’m not interested in events as such as a photographer, as a citizen of the country yes of course I am. But as a photographer, I am interested in the causes of events.”

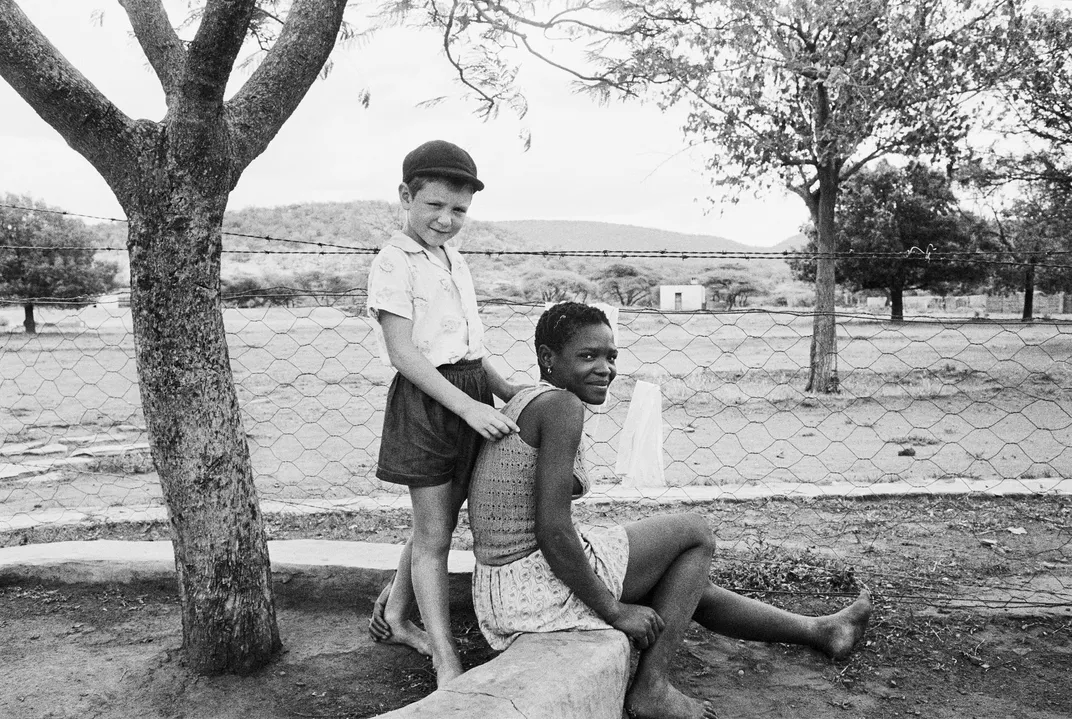

Goldblatt focused on the complex realities of daily life under an apartheid regime. In one photograph he shot in 1965, a white boy stands next to his black nursemaid, Heimweeberg, his hands resting delicately on her shoulders. Behind them stands a barbed wire fence.

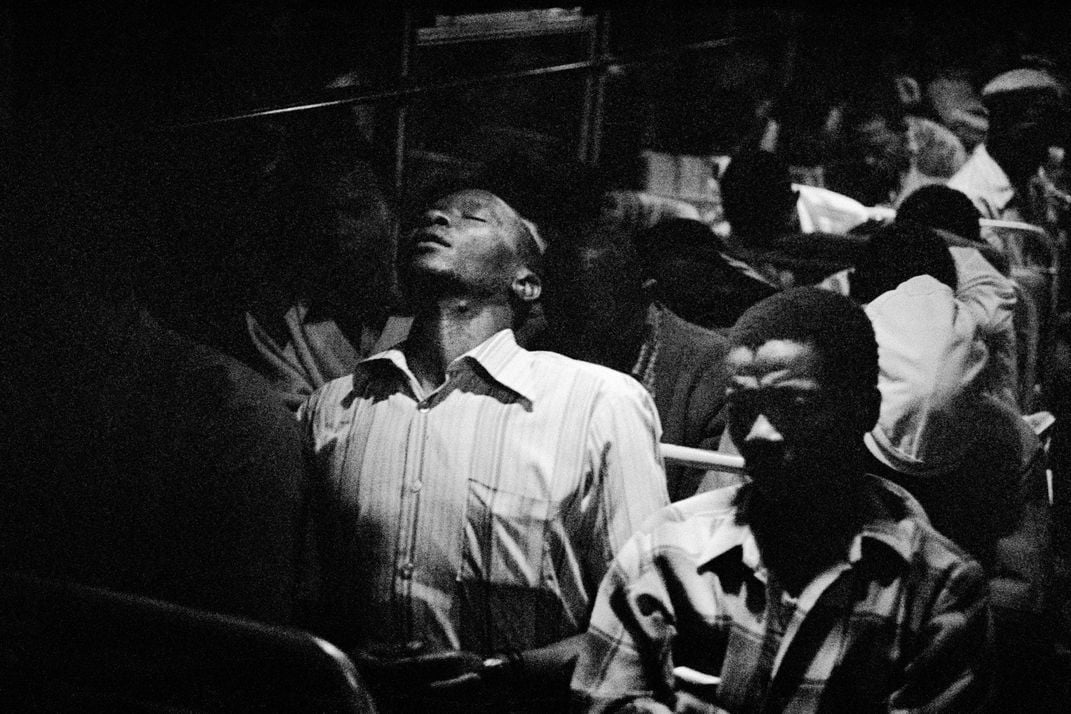

Goldblatt’s 1989 book, The Transported of KwaNdebele documents the hours-long commute to city centers that black South Africans made from the segregated areas where they were forced to live. In one iconic photograph, commuters can be seen on a bus, slumped over in exhaustion.

Goldblatt’s work was exhibited in museums throughout the world. In 1998, he became the first South African artist to be honored with a solo show at the MOMA in New York. This year, his photographs were showcased in a retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in Paris that closed in May.

Before he died, Goldblatt bequeathed his archive of negatives to Yale University. It was a controversial move; he had previously promised the trove to the University of Cape Town, but withdrew his collection after student protestors began burning campus artworks that they deemed to be "colonial symbols."

“Differences are settled by talk," Goldblatt told Natalie Pertsovsky of GroundUp in 2017. "You don’t threaten with guns. You don’t threaten with fists. You don’t burn. You don’t destroy. You talk. These actions of the students are the antithesis of democratic action."

For much of his career, Goldblatt worked in black-and-white; “color seemed too sweet a medium to express the anger, disgust and fear that apartheid inspired,” he once said, according to Genzlinger of the Times. In the 1990s, he began experimenting with color, but his mission to photograph South Africa through a lens of integrity and morality remained the same.

“I’m a plodder,” Goldblatt once told the British Journal of Photography. “If you look back at my work, it’s a straight-line graph with a few bumps. I’ve been doing the same thing for 60 years. Today I’m doing exactly what I was doing in the years of apartheid. I’m looking critically at the processes taking place in my country.”