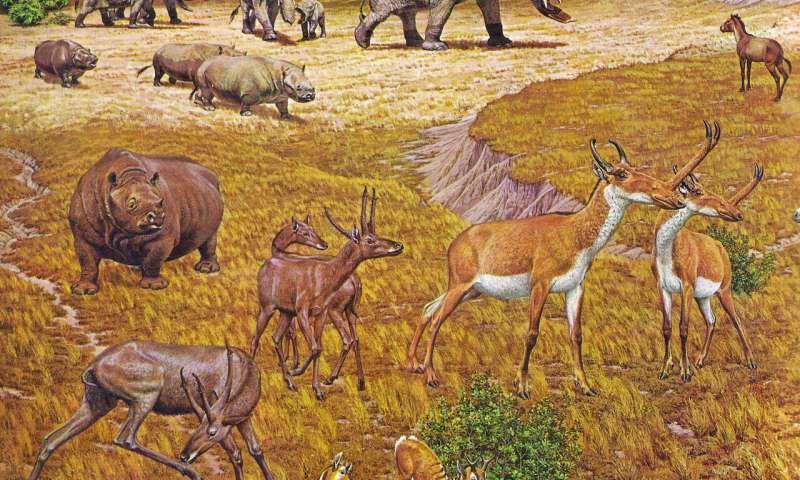

New Analysis of Depression-Era Fossil Hunt Shows Texas Coast Was Once a ‘Serengeti’

Over 11 million years ago, the area was full of animals

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/87/49/8749a403-8cba-4c87-992d-a6af2f242eb3/texas_bone.jpg)

Between 1939 and 1941, amateur paleontologists collected thousands of 11 to 12 million-year-old fossils from the Texas Coastal Plain. The project was part of the State-Wide Paleontologic-Mineralogic Survey funded by the Works Progress Administration, a government agency that created employment for roughly 8.5 million people nationwide, including turning some everyday Texans into bone hunters.

Now, their hard work is aiding modern researchers, who used the collection, stored at the University of Texas at Austin, to show that part of the Gulf Coast was the ancient equivalent of the Serengeti.

While other studies have looked at the survey bones before, George Dvorsky at Gizmodo reports that new research led by Steven May, research associate at UT Austin’s Jackson School of Geosciences, focused specifically on bones collected at four sites around Beeville, Texas.

For the study, the first to assess the entire Depression-era collection from the region, he and his team looked at roughly 4,000 specimens from 50 different species that lived along the ancient oceanfront. They found that 11 million to 12 million years ago, the area was full of animals: Rhinoceros, antelope and camels were common along with 12 species of horse-like animals and four rodents. They also found two bird species, seven reptiles, and five types of fish. The collection even included a new genus of an elephant-like animal called a gomphothere, an extinct relative of modern dogs, as well as the oldest alligator fossil unearthed in North America. The research appears in the journal Palaeontologia Electronica.

“It’s the most representative collection of life from this time period of Earth history along the Texas Coastal Plain,” May says in a press release.

There were, of course, problems with hiring untrained people to dig up fossils that the team had to account for. Naturally, the WPA workers tended to focus on large bones from large vertebrates. “They collected the big, obvious stuff,” May says. Because that didn’t offer the team a complete picture of the environment, they decided to supplement the Great Depression-era work by searching aerial photos and archival material in an effort to determine the original dig sites.

They pinpointed one on Buckner Ranch and returned to the area, looking for things unskilled fossil hunters may have overlooked, including rodent teeth and tiny bones. The effort added many new species to the original list.

According to the paper, there are still 86 large fossils encased in plaster from the area that need to be studied. The researchers also plan to conduct isotope analysis to understand the various diets and habitats found near the Beeville dig sites.

Texas wasn’t the only state to employ WPA workers to dig up fossils. In Oklahoma, work crews of the “Fossil Bones Project” dug up about 30,000 specimens. Crews working in Nebraska also unearthed thousands of bones and the University of California supervised WPA paleontology programs across that state.