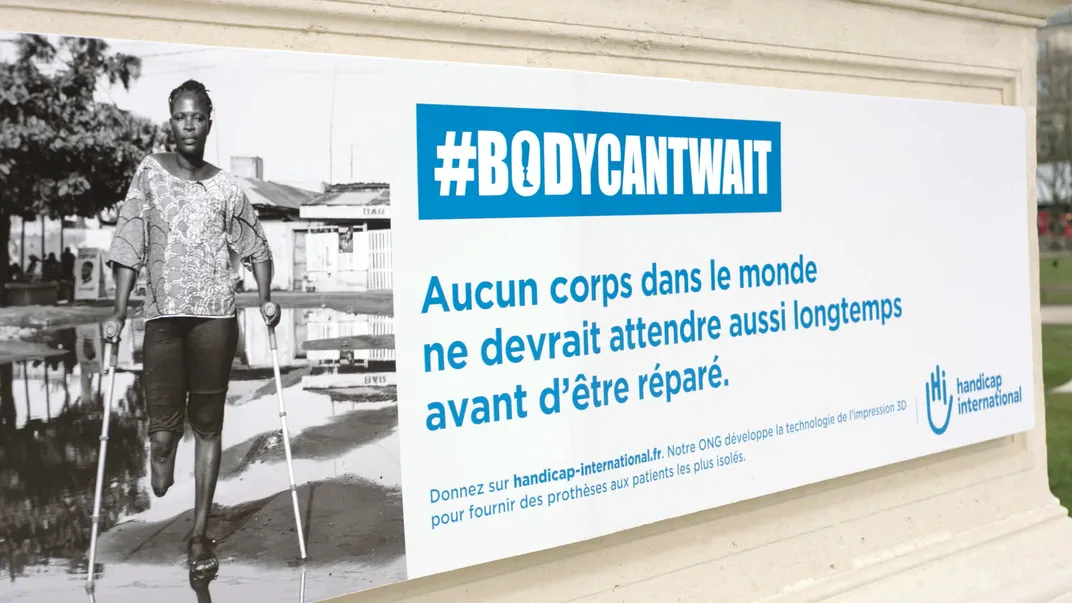

See Classic Sculptures Reimagined With Prosthetic Limbs

The aid organization Handicap International outfitted statues in France with prosthetic limbs to raise awareness about the global need for prostheses

Whether the Venus de Milo’s arms were lost when a fight over the possession of the work broke out upon the Hellenistic sculpture’s discovery in 1820 or they had previously broken off remains a question for the history books. Recently, though, residents of Paris were able to get a sense of how the famed sculpture might have once appeared to ancient viewers. As Claire Voon of Hyperallergic reports, the French chapter of the aid organization Handicap International outfitted original and replica classic sculptures with 3D-printed artificial limbs.

As part of a campaign to draw attention to the global need for prosthetics, earlier this month, a detailed replica of the Venus de Milo was temporarily erected at the Louvre-Rivoli metro station, which is located just outside the Louvre museum, where the original statue currently resides. Attached to the replica’s shoulders were two prosthetic limbs: one rested on the statue’s thigh, the other stretched outwards, clutching an apple in the palm of its hand. (The detail is based on the claim that one of the statue’s hands once held an apple.)

Handicap International also gave temporary prostheses to original statues in other locations in Paris, including the Jardin des Tuileries. The 18th-century sculpture “Alexandre Combattant” by Charles-Francois Leboeuf was fitted with a right forearm and a sword. Advocates placed another prosthetic arm on a statue depicting the abduction of Deianira, Hercules’ wife, by the centaur Nessus; Deianira could be seen flinging her new limb upward in despair.

The initiative is part of Handicap International’s #BodyCantWait campaign, which seeks to raise awareness about the 100 million people around the world who need prosthetic limbs. The organization also hoped to highlight the effectiveness of 3D prosthetics, which are relatively easy to produce.

“Before 3D printing, you had to make a plaster cast of the stump, adjust it four or five times, encase it in resin, things that required trained professionals and lots of equipment,” Xavier de Crest, head of Handicap International France, tells the AFP, according to RFI. Now, a small scanner can do the job of taking measurements and sending them to modeling software, and, ultimately, a 3D printer for production.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/87/ac/87acfa1c-ab5d-4278-9ad8-fee4a82ff221/2.jpg)