Five Things to Know About China’s Falling Space Station

For one, it’s exceedingly unlikely to cause you harm

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ae/01/ae01d7c0-2e40-46cf-9144-7d64081196af/china-tiangong-1-credit-cmsa.jpg)

Sometime around April 3—give or take about a week—China’s 9.5-ton Tiangong-1 space station will fall out of orbit and enter Earth’s atmosphere. While media reports for the last few months have hyped the “uncontrolled” de-orbit as a potential threat, you probably don’t have to worry.

As Laura Geggel at LiveScience reports, though scientists aren’t sure exactly where the space station would impact, the most recent analysis suggests that the majority of the craft will likely burn up in orbit. And the chances of getting struck by any debris that makes is through are beyond miniscule. Here are five things to know about the station and its descent before its final act.

Tiangong-1 was never intended to be a permanent space base

Launched in 2011, Tiangong-1 was China's first space station, and was intended as a training platform for a much larger space station scheduled to launch in the 2020's. (For political reasons, the Chinese have not been allowed to participate in the International Space Station.) It was never intended as a permanent fixture, having only a two-year planned operational lifespan, according to a 2011 press release. The space station allowed China to practice docking procedures, and according to the Aerospace Corporation, they conducted an unmanned mission to the station in 2011 along with two manned missions in 2012 and 2013. Though its imminent re-entry wasn't necessarily planned, the station already had exceeded its expected lifespan when China announced its descent to Earth in 2016.

The “fall” was officially announced two years ago

In March, 2016, China announced it had lost control of the craft, and international agencies and amateur astronomers have been tracking it ever since. “It’s a Chinese satellite so we don't totally know what's going on, but as far as we can tell, 2015 was the last time the Chinese government ever sent a control to it,” Cambridge astronomer Matt Bothwell tells Phoebe Braithwaite at Wired. “It’s been monitored by amateur satellite trackers, this community of people that study what's in space, and its behavior is totally consistent with something that’s not being powered.”

Where will it land?

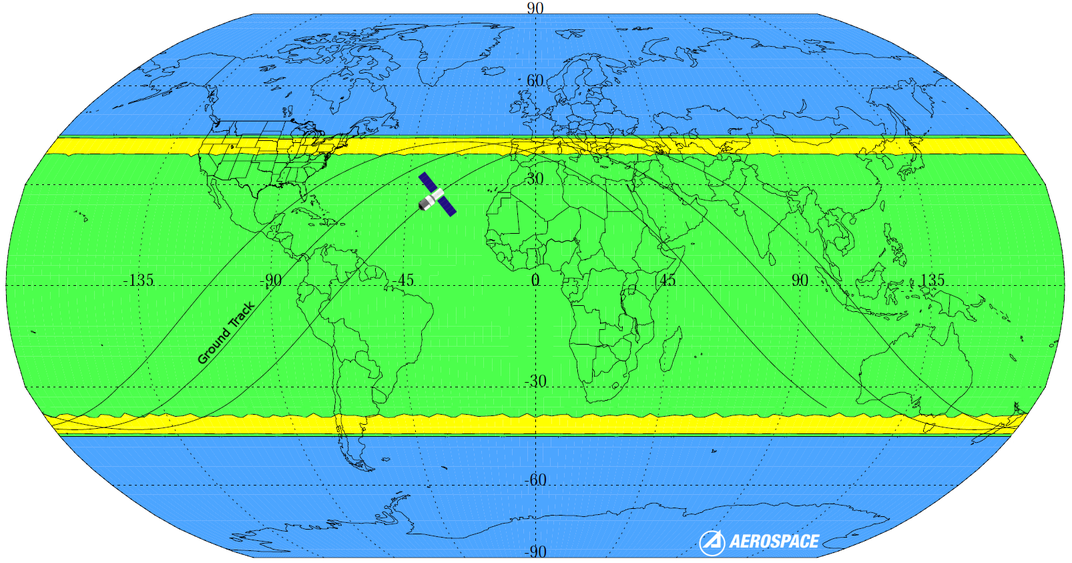

According to Aerospace Corporation's latest prediction, the craft is likely to re-enter along two narrow bands at 43 degrees north and 43 degrees south latitude, putting parts of China, southern Europe, the northern U.S., as well as parts of South America, Tasmania and New Zealand in its likely path. The agency says there is zero probability of impact for about a third of Earth’s surface.

It’s exceedingly unlikely debris will hit anyone

Once it enters Earth’s atmosphere, the vast majority of the craft will vaporize, causing it to light up skies like a shooting star on steroids. As Braithwaite reports, denser parts of the station—like engines or batteries—may survive with chunks as large as 220 pounds making it to the surface.

But don’t go ducking for cover. As Geggel reports, the odds of someone getting smacked with a chunk of the space station is a million times smaller than the odds of winning the Powerball, which is roughly one in 292 million. In fact, according to the Aerospace Corporation, despite about 5,900 tons of space debris raining down over Earth in the past half century, there only has been one reported person struck with these scraps. Lottie Williams of Tulsa Oklahoma was hit with a six-inch piece of metal from a Delta II rocket falling out of orbit in 1996. She was not injured.

Similar re-entries are actually pretty common

“In the history of the Space Age, uncontrolled re-entries have been common," Jonathan McDowell of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics told Smithsonian.com in 2016 when panicked reports started surfacing about Tiangong-1's descent.

For example, in 1978, the United States’ first manned space station, SkyLab, began de-orbiting after eight years in space. Elizabeth Hanes at History.com reports that in order to save money, engineers did not give it a way to reorient or navigate on the way down. Fearful that the 77-ton space torpedo would fall on a populated area, NASA came up with a plan for the newly created space shuttle to bump the lab into higher orbit where it would remain indefinitely. But that plan never came to pass and in July 1979 NASA ignited the craft’s booster rockets, hoping it would push SkyLab into the Indian Ocean. It only partly worked. Though chunks did enter the ocean, the station broke up on entry and littered a swath of unpopulated land in Western Australia.