Descendant’s DNA Helps Identify Remains of Doomed Franklin Expedition Engineer

New research marks the first time scholars have confirmed the identity of bones associated with the fateful Arctic voyage

:focal(470x252:471x253)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d8/a7/d8a7bb9b-df9f-4c87-be8a-d8a40777a4a4/2021050414058-04c6f93bdb89c8ce4c03198565795de99d35d57db3ff7990ce949962cb4f408c-jpg.jpeg)

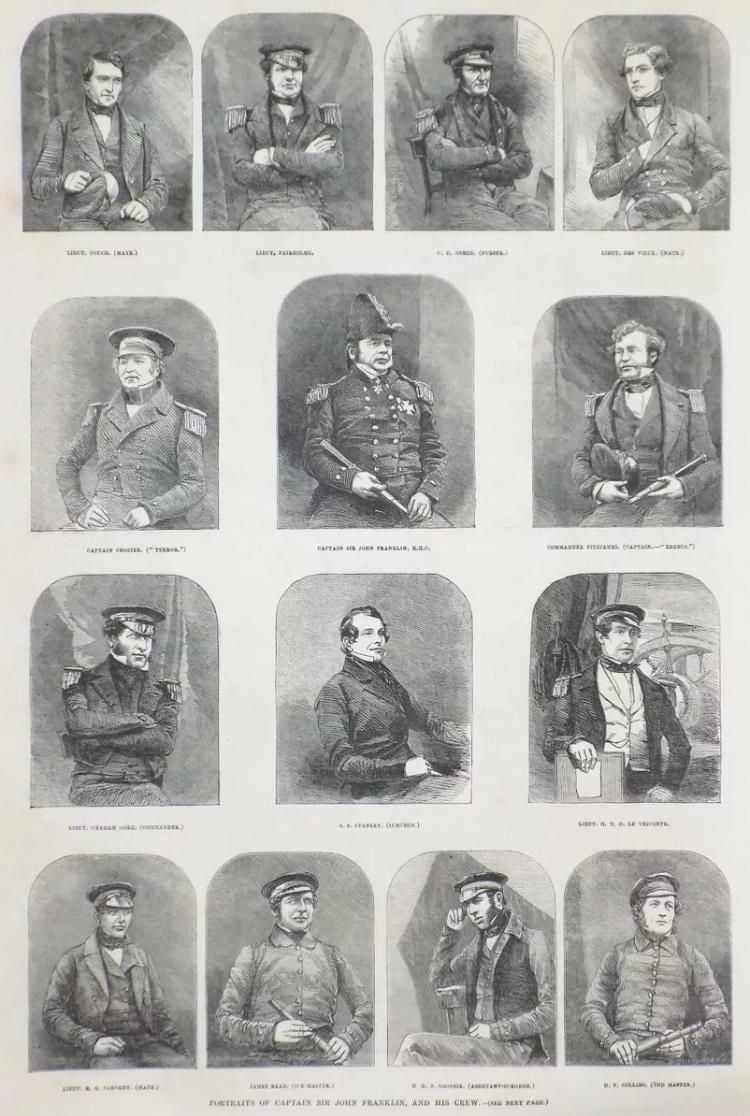

In May 1845, British Naval officer John Franklin and his crew embarked on a doomed voyage to the Northwest Passage. One of the deadliest polar expeditions in history, the journey ended in tragedy, with none of the 129 men on board the HMS Terror and HMS Erebus ever returning home.

Some 175 years after the Franklin Expedition’s disappearance, researchers have made the first DNA identification of one of the Arctic quest’s crewmembers. The team published its findings last month in the journal Polar Record.

As Yasemin Saplakoglu reports for Live Science, the scholars matched DNA from the teeth and bones of one of the voyage’s victims to the great-great-great grandson of engineer John Gregory, who was on board the Erebus when it became stuck in Arctic ice off of Canada’s King William Island.

“The news came by email and I was at work,” descendant Jonathan Gregory of Port Elizabeth, South Africa, tells Bob Weber of the Canadian Press. “I literally needed to hold on to my seat when I was reading.”

Previously, the last known record of Gregory was a letter to his wife, Hannah, and their five children. The missive was posted from Greenland on July 9, 1845, before the ships entered the Canadian Arctic, according to a statement.

“Give my kind Love to Edward, Fanny, James, William, and kiss baby for me,” the sailor wrote, “—and accept the same yourself.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/55/96/5596833f-3adb-481e-be00-f1252703b04b/hms_erebus_and_terror_-_iln_1845.jpeg)

The Franklin Expedition set out from England on May 19, 1845. Per Canadian Geographic, the group’s ships held desalinators used to make salt water drinkable and three years’ worth of food.

In 1847, the crew decided to sail into the wider western passage of Victoria Strait rather than a narrower southeastern passage. But the sea ice “proved too much … to handle,” and both ships got stuck, notes Canadian Geographic. By April 1848, reports the Times, Franklin and some 24 other members of the expedition had died, leaving the survivors (including Gregory) to set out on foot in search for a trading post. None of them made it.

Gregory’s remains, along with those of two other men, were found on the southwest shore of King William Island, about 50 miles south of the site where the ships became stuck, in 1859. Researchers excavated and examined the bones in 2013 before returning them to the grave with a new plaque and memorial cairn.

Lead author Douglas Stenton, an anthropologist at the University of Waterloo, tells the New York Times’ Bryan Pietsch that Gregory most likely died within a month of leaving the Erebus, after a journey that “wasn’t necessarily an enjoyable trip in any sense of the word.” He was just 43 to 47 years old.

Dozens of search parties sailed to the Arctic in hopes of finding the lost expedition. Rescuers heard reports by local Inuit people of starving men who had resorted to cannibalism, but as Kat Eschner wrote for Smithsonian magazine in 2018, scandalized Victorians back home in England refused to believe these accounts. In the decades that followed, searchers discovered scattered grave sites linked to the voyage, as well as a note—buried in a stone cairn—describing the disasters the group had endured.

The wreck of the Erebus was only found in 2014. The Terror followed two years later. As Megan Gannon reported for Smithsonian in 2020, researchers stymied by the Arctic cold have only been able to investigate the ships for five to six weeks each year. In 2019, divers conducted their first systematic excavation of the Erebus, recovering more than 350 artifacts, including dishes, items of clothing and a hairbrush.

Aside from Gregory, researchers have extracted DNA from the remains of 26 crewmembers buried at nine different sites. Per the statement, they have used that information to estimate the men’s age at death, height and health. The team is asking descendants of other expedition members to provide DNA in order to help identify the remains.

By matching the bones to their owners’ names, Stenton tells the Times, scholars hope to “identify some of these men who [have] effectively become anonymous in death.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)