Dragonflies Embark on an Epic, Multi-Generational Migration Each Year

Monarch butterflies aren’t the only migratory marathoners in North America

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/92/e1/92e16dad-3cd0-4832-a9e2-33f644011f49/green_darner.jpg)

The green darner dragonfly, Anax junius, embarks on a rigorous, multi-generational migratory relay race up and down North America every year that largely goes unnoticed, according to a new study published in the journal Biology Letters.

Dragonfly experts knew that the common emerald green and blue insects migrated, but tracking the jet-setting three-inch-long insect is tricky. The slender insects are too small for radio trackers and don’t travel in easy-to-spot swarms like monarchs or birds. To bring the details of the dragonfly’s journey to light, researchers consulted 21 years of data collected by citizen scientists and analyzed more than 800 green darner wing samples collected over the last 140 years from museums, reports Susan Milius at Science News.

The team tested each wing sample for a chemical code that would indicate approximately where the bugs were born. From there, the researchers could figure out how far the dragonflies travelled as adults. To do so, they tested for three hydrogen isotopes—or chemical signatures—each of which vary geographically. Hydrogen accumulates in dragonfly larvae’s chitin, which is the stuff that eventually makes up their wings as adults. Identifying the isotope in each wing sample allowed researchers to narrow in on the dragonflies’ origin. The isotopes aren’t perfect, but they’re good enough to tell whether they originate in “Florida, Maryland or Maine,” reports Ben Guarino at The Washington Post.

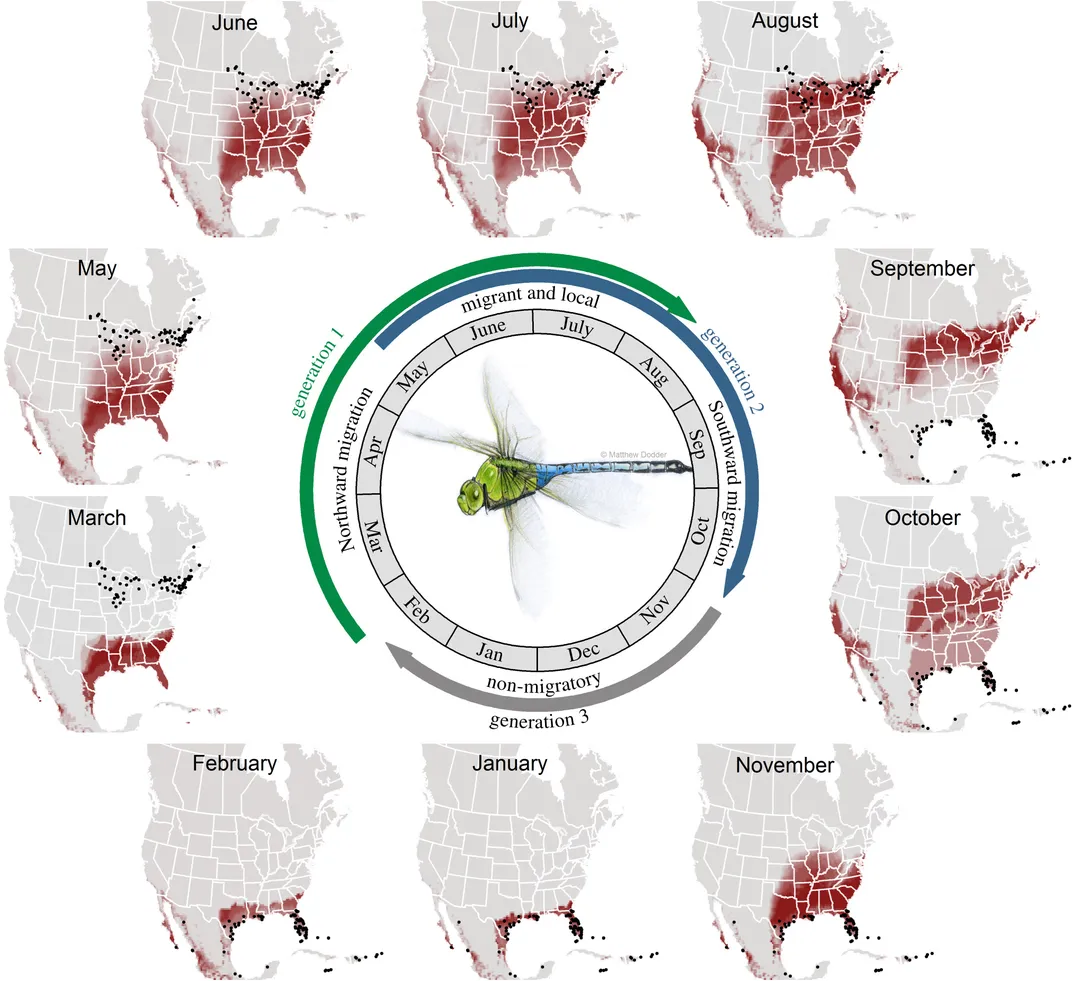

The citizen science data allowed the team to figure out what types of natural cues, like temperature, give the dragonfly larvae the signal to emerge and migrate. Between February and March, the first generation of dragonflies emerges from ponds and lakes in the southern United States, Mexico and the Caribbean. Then those resilient first-gen bugs travel hundreds of miles north as, making it to New England or the upper Midwest by May. When they get there, they’ll lay their eggs and die.

The lives of the next generation are just as incredible. While some of those second generation insects will hang out and overwinter in ponds and lakes in the north during their nymph stage, many will reach maturity and head south between July and October.

When those insects reach the south, they deposit another batch of eggs, which mature into a third generation that will live a non-migratory life over the winter on the coast, producing the eggs of the dragonflies that will migrate northward again in the spring.

“We know that a lot of insects migrate, but we have full life history and full migration data for only a couple. This is the first dragonfly in the Western Hemisphere for which we know this,” senior author of the paper Colin Studds of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, says in a press release. “We’ve solved the first piece of a big mystery.”

The bigger part of the mystery—and one that applies to migrating butterflies and even birds—is how the insects know what path to take north and south and when they know to migrate. The data suggest that the insects begin migrating north once temperatures reach 48 degrees, Studds tells Guarino at The Washington Post. This may also happen because the days start to grow longer during this time as well.

Understanding the migration patterns of these and other insects is important because insects across the globe are experiencing a huge population crash. Learning their life histories can help researchers figure out why they are disappearing. One of the study’s co-authors Michael Hallworth of Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center says the data can also help monitor the impacts of our warming world.

“With climate change we could see dragonflies migrating north earlier and staying later in the fall, which could alter their entire biology and life history,” he says.