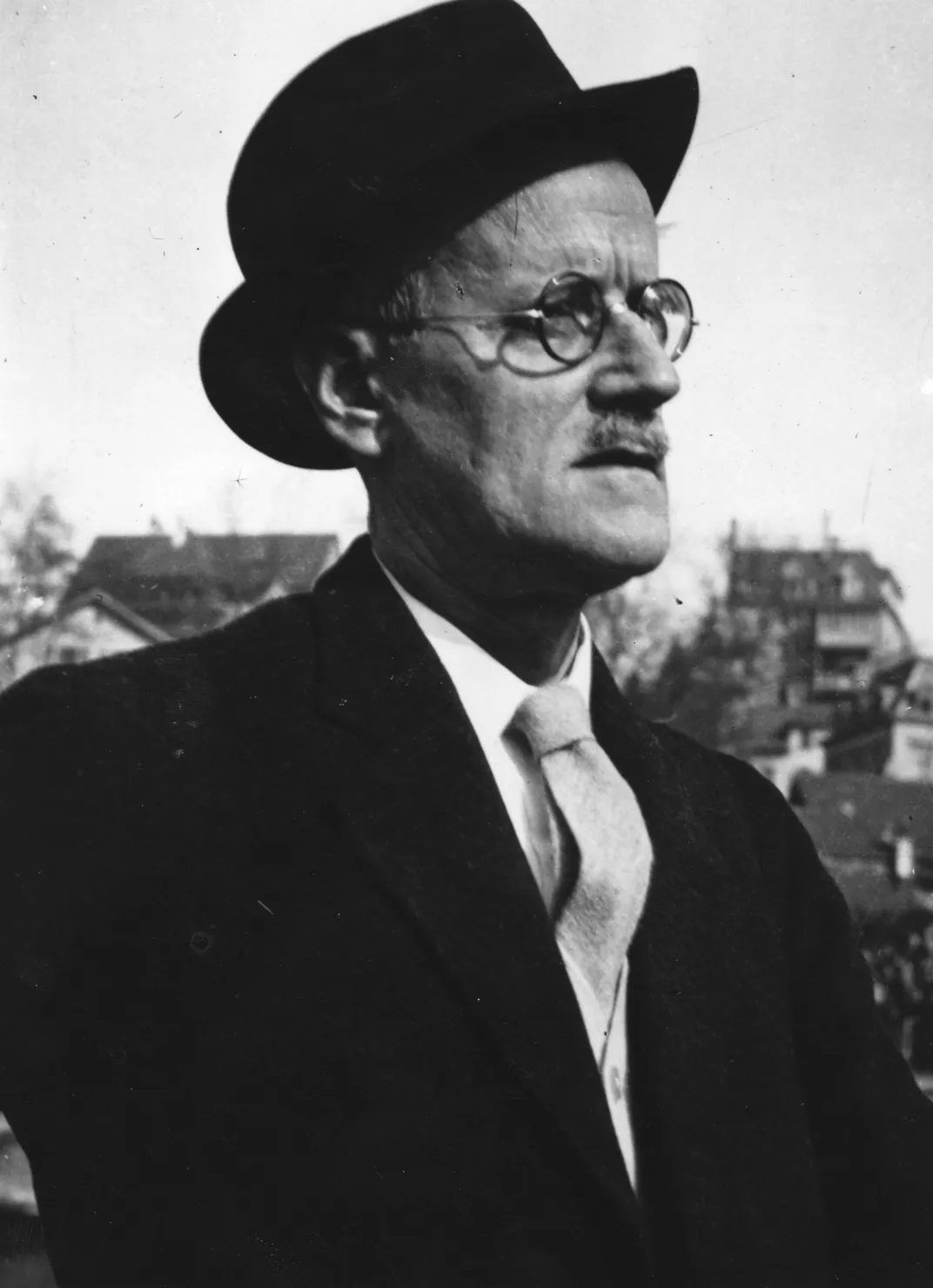

Dublin Wants to Reclaim James Joyce’s Body Before the Centenary of ‘Ulysses’

Critics question whether the author, who died in Zurich after a 30-year exile, ever wanted to return home, even in death

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/81/e6/81e6c78c-30d5-47d3-a874-a89a3e77321e/gettyimages-1176350723.jpg)

James Joyce is perhaps literature's most well-known exile. The writer, then 22, left his home country in 1904, abandoning Ireland in favor of Paris, Zürich and the Italian city of Trieste. He made his last visit to the island nation in 1912—a full 29 years before his death in 1941.

Despite the fact that Joyce essentially gave his native Dublin the cold shoulder, the Irish capital has long touted its connection with this wayward one-time resident. As Sian Cain reports for the Guardian, the Dublin City Council recently announced a proposal aimed at transferring the Ulysses author’s body from his current resting place in Zürich to the Emerald Isle. The move has ignited a debate surrounding Joyce’s personal wishes and legacy, with scholar Fritz Senn, founder of the Zurich James Joyce Foundation, saying the plan “will end in nothing.”

City councilors Dermot Lacey and Paddy McCartan introduced a motion to exhume the writer’s body and that of his wife, Nora Barnacle, last week. They hope to rebury the couple’s remains in the Irish capital prior to the 2022 centenary of Joyce’s most famous novel, Ulysses. This plan, Lacey and McCartan argue, would honor the wishes of both Joyce and his wife.

Speaking with Irish radio station Newstalk, McCartan—as quoted by the Guardian—says, “There may be people who are not fans of this and want to let sleeping dogs lie.”

He adds, “Joyce is a controversial figure, there are no doubts about that. Exile was a key element in his writing, but for it to follow him into eternity? I don’t think that was part of the plan.”

As Alison Flood writes in a separate Guardian article, the plan has already generated backlash, especially from Joyce lovers based in Zurich.

“All I know is that there seems to be no evidence that Joyce wanted to return to Ireland or even be buried there,” Senn, who founded the Zurich James Joyce Foundation 30 years ago, tells Flood. “He never took Irish citizenship when he could have done it” —namely, after the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922. Instead, Joyce chose to remain a British citizen until his death.

It’s unclear exactly what Joyce, who died while undergoing surgery for a perforated ulcer at age 58, planned for his remains. After her husband’s death, Barnacle asked the Irish government to repatriate his remains, but her request was refused. Flood also reports that two Irish diplomats stationed in Zurich at the time of Joyce’s passing failed to attend his funeral. The country’s secretary of external affairs did send message to the diplomats, but he was chiefly concerned with whether the writer had recanted his atheistic tendencies: “Please wire details about Joyce’s death. If possible find out if he died a Catholic.”

Ireland’s emphasis on religion was one of the factors that drove Joyce out of his native land. Although he chafed at the country’s religious orthodoxy, conservatism and nationalism, all of his major works—including A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Dubliners and Ulysses—are intimately entwined with Ireland’s people, history and politics.

In an essay for the Irish Times, Jessica Traynor, a curator at Dublin’s Irish Emigration Museum, explains, “He couldn’t bear to live in Dublin, [but] Joyce’s spiritual and artistic engagement with the city continued until the end of his life.”

As an expatriate, Joyce loved to quiz visitors from home about the shops and pubs on Dublin’s streets. Still, Traynor writes, Irish censorship complicated the author’s relationship with his native country, finding him locked in prolonged battles to get Dubliners and Ulysses published. Both works were criticized for their obscenity and ostensibly “anti-Irish” content.

In the decades since Joyce’s death, his grave in Zürich’s Fluntern cemetery has become a major tourist attraction. Barnacle was buried alongside her husband a decade later; the couple’s son George and his second wife, Asta Osterwalder Joyce, are also buried at the site.

A spokesperson for Irish Culture Minister Josepha Madigan tells the Journal.ie’s Conor McCrave that she is aware of the proposal but has not yet received a formal request for repatriation: “The Minister appreciates the literary achievement and enduring international reputation of James Joyce,” the representative says. “The suggested repatriation of the remains of James Joyce would be a matter in the first instance for family members and/or the trustees of the Joyce estate.”

Senn, meanwhile, tells McCrave he doesn’t think Joyce’s family is necessarily interested in moving the writer’s body, adding, “The most important thing is you would need the consent of his grandson, Stephen Joyce, and if I had to bet on it, I bet he would vote against it.”

The Swiss scholar also points out that the people of Zurich will probably resist giving up their adopted literary hero, setting the stage for a contentious battle over Joyce and his relatives’ remains.

According to Cain, a previous 1948 attempt to repatriate Joyce’s remains failed to gain traction. That same year, however, a campaign to return poet W.B. Yeats’ bones to his native Sligo succeeded. Still, if Yeats’ story offers any lessons, it’s that Joyce may be better off remaining where he is: As Lara Marlowe reported for the Irish Times in 2015, the Nobel Prize-winning poet was buried in the Riviera town of Roquebrune-Cap-Martin after he died in 1939. Unfortunately, the advent of World War II made it impossible to return Yeats’ body to Ireland until 1948. By that point, locals had already disinterred the bones and deposited them into an ossuary alongside other sets of remains. The diplomat assigned to return the body picked out the bones he thought might belong to Yeats, assembling a full skeleton from the mixture of parts, but it’s highly likely the majority of remains in his grave at Drumcliffe Churchyard actually belong to other people.