Earth Loses 1.2 Trillion Tons of Ice Per Year, a Nearly 60% Increase From 1994

A pair of studies paint a worrying picture of accelerating ice loss around the world, with serious consequences for projections of sea level rise

:focal(754x466:755x467)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9a/05/9a055805-ec90-4322-86e7-a48dd5bf1944/254198_web.jpg)

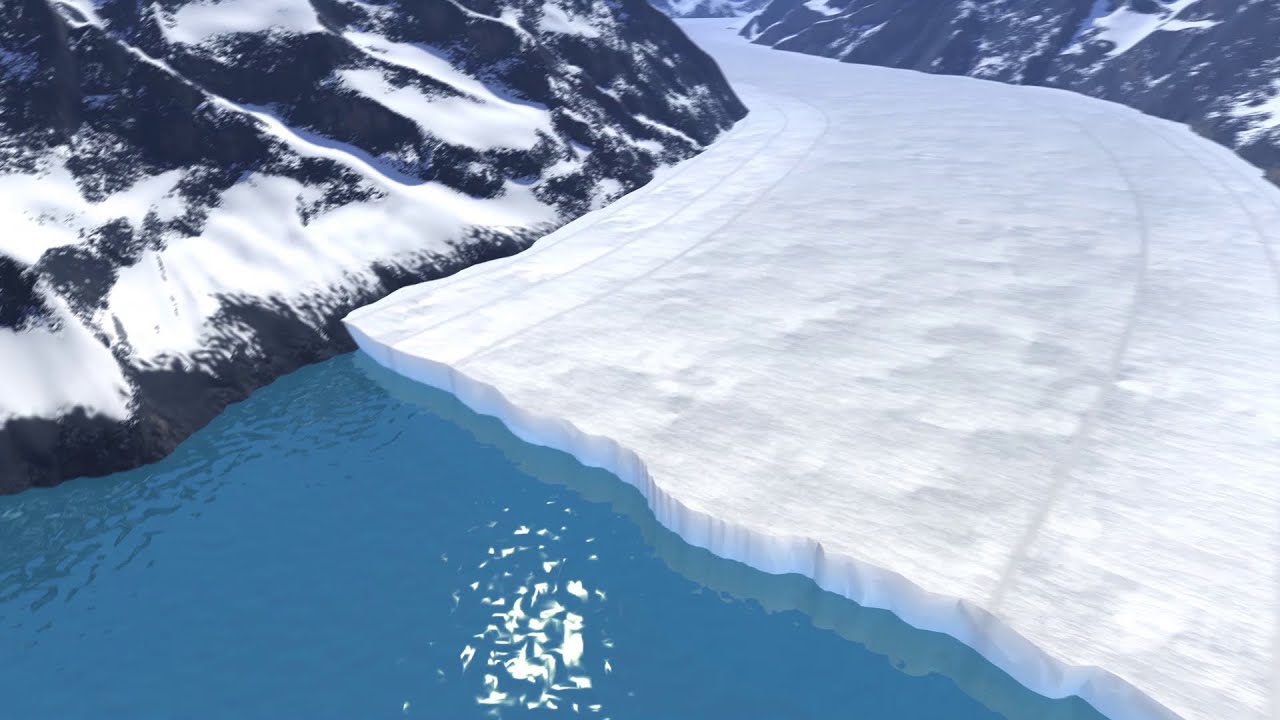

A new study finds that Earth lost 28 trillion tons of ice between 1994 and 2017, reports Chelsea Harvey for E&E News.

In a clear illustration of climate change’s worrying acceleration, the rate at which our planet is losing its ice skyrocketed from an average annual loss of roughly 760 billion tons of ice in the 1990s to more than 1.2 trillion tons per year in the 2010s, according to the study published this week in the journal Cryosphere.

Human activities, which have warmed our planet’s atmosphere and oceans by 0.47 degrees Fahrenheit and 0.22 degrees Fahrenheit per decade since the 1980, respectively, drove the massive ice loss.

This study’s staggering total of lost ice is the first global assessment that accounts for the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets, Arctic and Antarctic sea ice, as well as ice lost from mountain glaciers the world over, according to E&E News. All told, the massive loss of ice has raised global sea levels by 1.3 inches since 1994.

“The ice sheets are now following the worst-case climate warming scenarios set out by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC),” says Thomas Slater, a climate researcher at the University of Leeds and the Cryosphere study’s lead author, in a statement. “Sea level rise on this scale will have very serious impacts on coastal communities this century.”

The IPCC’s estimates suggest that ice loss could raise sea level by up to 16 inches by 2100.

A second study, published earlier this month in the journal Science Advances, suggests that Earth’s ice loss is unlikely to stop accelerating, report Chris Mooney and Andrew Freeman for the Washington Post. The Science Advances paper finds 74 major ocean-terminating glaciers in Greenland are being weakened from beneath by intruding waters from warming seas.

“It’s like cutting the feet off the glacier rather than melting the whole body,” Eric Rignot, a study co-author and a glacier researcher at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the University of California at Irvine, tells the Post. “You melt the feet and the body falls down, as opposed to melting the whole body.”

Speaking with the Post, Rignot says the study’s results suggest current estimates of sea level rise’s progression may be overly conservative. “As we peer below we realize these feedbacks are kicking in faster than we thought,” he says.

The worst-case scenario projected by the IPCC—the one that the Cryosphere study suggests Earth is currently tracking—might not actually be the worst-case scenario. Instead, ice loss and sea level rise could progress more rapidly than even the IPCC’s most pessimistic projections unless more is done to account for warm ocean water undercutting glaciers like the 74 in Greenland that the Science Advances paper identifies. Per the Post, the IPCC’s next report is expected later this year.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/alex.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/alex.png)