Earth Lost 2.5 Billion Years’ Worth of Evolutionary History in Just 130,000 Years

Even if humans curbed destructive actions within next 50 years, it would take between five to seven million years for mammal biodiversity to fully recover

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/82/7d/827deb8f-29ad-47e7-afd0-b73201b1a38f/1024px-elephas_maximus_bandipur.jpg)

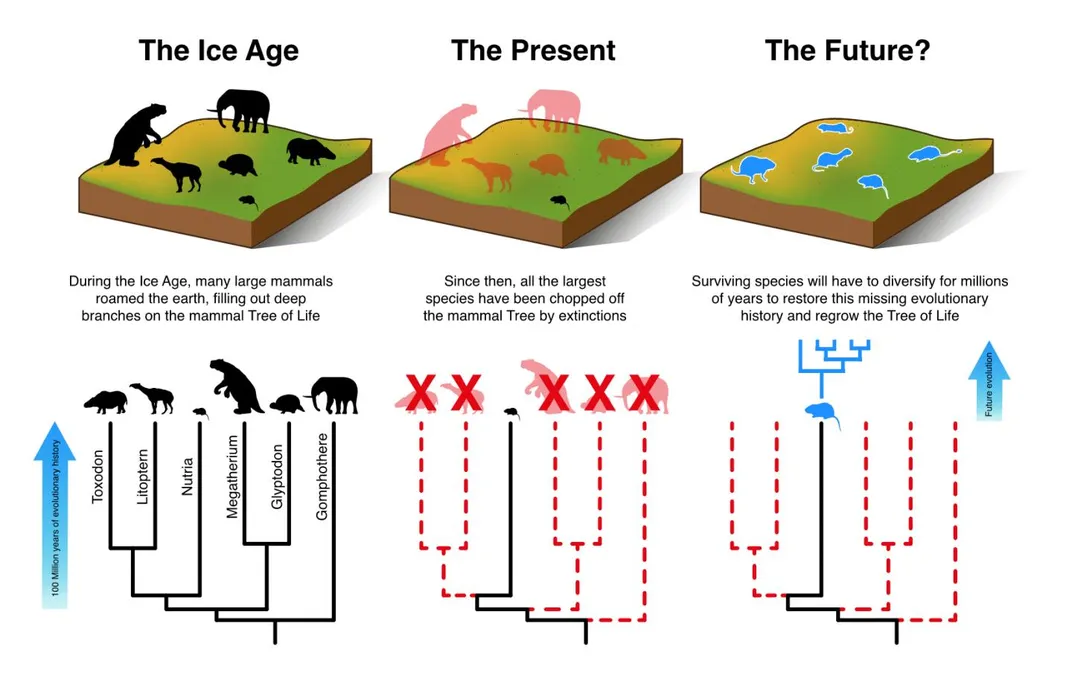

Humans have only been around for some 130,000 years, but a new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences concludes that in this relatively brief time period, we’ve managed to erase a staggering 2.5 billion years of evolutionary development by driving more than 300 mammal species into extinction.

These findings, led by paleontologist Matt Davis of Denmark’s Aarhus University, paint a grim portrait of Earth’s future—especially in light of a recent United Nations report that predicts widespread drought, flooding, extreme heat and poverty will overtake the planet if drastic action isn’t taken immediately.

As Damian Carrington reports for The Guardian, Davis and his colleagues foresee similarly dire straits for Earth’s non-human residents, many of whom are threatened by poaching, pollution and habitat destruction. Even if humans curbed these destructive actions within the next 50 years, it would take between five to seven million years for mammals to repopulate the world with the same level of biodiversity seen before the advent of modern humans and three to five million years to return to the level of biodiversity Earth currently boasts.

If this timeframe is difficult to visualize, consider a helpful piece of context provided by The Atlantic’s Ed Yong: The time needed for mammals to recover is at least ten times as long as humans have existed as a species. This makes the healing process, according to Davis, incomprehensible “on any kind of time scale that’s relevant to humans.”

To calculate mankind’s toll on the world’s wildlife, researchers relied on a metric known as phylogenetic diversity. Cosmos’ Samantha Page explains that this figure takes into account the amount of time an endangered or extinct species took to evolve, whereas the more commonly cited measure of biodiversity simply tracks the number of species present on Earth.

Take shrews and elephants, for example. As Davis tells The Guardian’s Carrington, there are hundreds of varieties of the mole-like critters but just two elephant species. If elephants went extinct, the effect on phylogenetic diversity would be equivalent to chopping off a large branch on the tree of life. Losing a single shrew species, on the other hand, would be like trimming a small twig.

Page offers another way of looking at extinction, comparing the pygmy sloth, which split off from its closest relatives just 8,900 years ago, to the aardvark, which split off 75 million years ago. As the sole remaining species of the Tubulidentata order, the aardvark represents a singular lineage that will be difficult to replace if the animal goes extinct.

According to The Atlantic’s Yong, modern humans wiped out two billion years of mammals’ evolutionary history by the 16th century. Since then, the pace of destruction has rapidly sped up. We lost another 500 million years between 1500 C.E. and the present, and if scientists’ projections prove correct, we’ll lose another 1.8 billion years within the next five decades.

Previous studies have found that early human activity disproportionately affected megafauna, or huge mammals such as giant beavers, armadillos and deer. As Davis tells Yong, these losses are particularly devastating because mega mammals tended to be Earth’s “most evolutionary distinct,” often forming their own branches on the tree of life.

Today, rhinoceroses and elephants are two of the last remaining animal giants, but an Aarhus University press release states that black rhinos are at a high risk of going extinct within the next 50 years, while Asian elephants have less than a 33 percent chance of lasting beyond the 21st century.

All in all, the new findings offers little hope for animal lovers. Prioritizing conservation of phylogenetically diverse creatures, including the black rhino, the red panda and a large lemur species called the indri, could stem the loss of evolutionary history, but as Duke University’s Stuart Pimm, a conservation ecologist who was not involved in the study, tells Carrington, such targeted conservation is difficult in practice.

“It is hard to imagine that a full recovery or either phylogenetic or functional diversity [a measure of the role animals play in their environment] can be achieved within human time-scales,” Shan Huang, an ecologist at the Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Center who was also not involved in the study, tells Yong. “But by prioritizing conservation for unique and distinctive lineages, we can at least slow down the losses.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)