A History of El Greco’s Masterful—and Often Litigious—Artistic Career

A 57-work retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago charts the evolution of the 16th-century painter’s distinctive style

:focal(611x297:612x298)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f8/83/f883a47b-f902-482c-89d3-8780e8538ab4/assumption_of_the_virgin.jpg)

Before he became “El Greco,” the renowned Old Master admired by the likes of Pablo Picasso, Paul Cézanne and Eugène Delacroix was simply Doménikos Theotokópoulos (1541–1614), an icon painter from Crete. It took decades, multiple moves and a handful of professional setbacks for the painter, whose nickname translates to “the Greek,” to develop his signature style: the lurid colors and eerie, elongated figures that continue to unnerve audiences to this day.

“El Greco: Ambition and Defiance,” a newly reopened retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago, unites more than 57 works to chart the artist’s entrepreneurial career, from his early paintings of religious icons to later portraits and private commissions. The show, which debuted in March but temporarily shuttered due to the Covid-19 pandemic, will welcome visitors through October 19. Those unable to visit the museum in person can explore the show’s online resources, including a virtual tour led by curators.

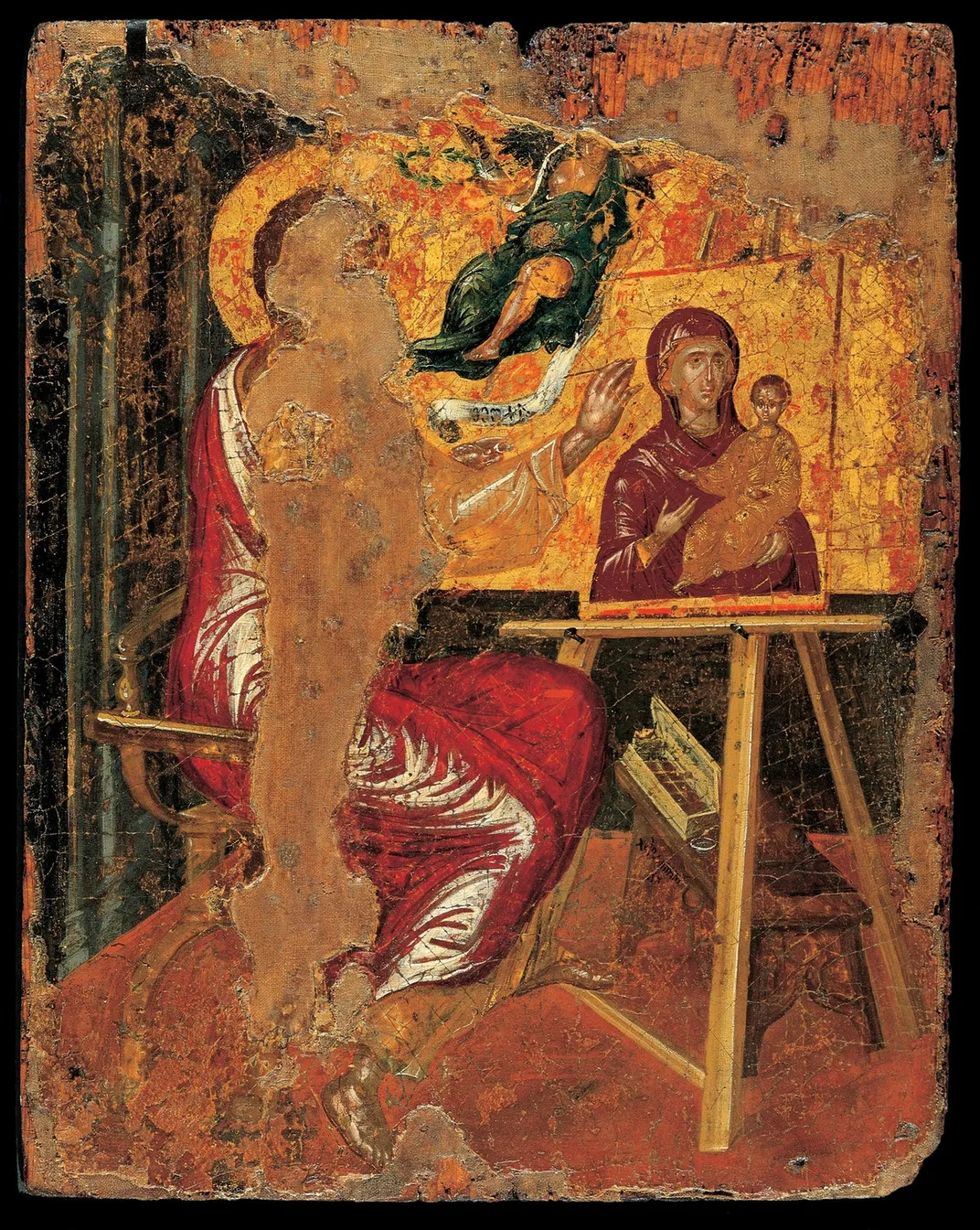

As a young man, El Greco likely trained as an apprentice to a Byzantine icon painter. The exhibition contains a rare example of the artist’s work from this period: St. Luke Painting the Virgin (1560-7). Icons like these were painted onto gilded wooden panels and used as items in private religious devotion, writes Ginia Sweeney in an Art Institute blog post.

In 1567, after achieving significant success as an icon painter, El Greco moved to Venice, where he radically altered his artistic style by studying the work of Titian, Tintoretto and Michelangelo, according to Kyle MacMillan of the Chicago Sun-Times.

Curator Rebecca Long draws attention to El Greco’s ambitious—and often litigious—streak. He moved to Rome six years after Michelangelo died, and as Marc Vitali reports for WTTW News, modeled many of his works during this period after the Sistine Chapel painter.

But El Greco wasn’t overly enamored with Michelangelo: In the margins of one of his books, he wrote a note suggesting the earlier artist “could draw, but he didn’t know anything about color,” Long tells WTTW. “He was very dismissive.”

During the Renaissance, successful artists relied on the patronage system, which found wealthy individuals commissioning and closely controlling the production of different masterpieces. According to an Art Institute timeline, El Greco’s lifetime of legal troubles began as early as 1566, when a Venetian nobleman sued him—likely because he had breached a commission contract. In 1579, El Greco waged multiple legal battles with the Toledo Cathedral after he refused to change aspects of The Disrobing of Christ (1577).

“We know a lot more about El Greco than we do other artists of the period thanks to all the records of the trials and lawsuits and everything else,” says Long in the virtual exhibition tour. “We really have a sense of him as a person and of what he wanted for his career. And they’re the same basic struggles that anyone who’s trying to make it as an artist faces, even though it was 400 years ago.

After El Greco faced thorny legal battles over commissioned works from institutions, he pivoted to painting for private citizens, Long explains. When he failed to secure the patronage of major churches or Philip II of Spain, the artist established a successful workshop in Toledo, where he lived the rest of his days—and earned his enduring nickname.

“For many wealthy Toledans, El Greco was the artist they wanted,” notes Richard Kagan, a historian at Johns Hopkins University, in the virtual tour. “It’s like going out and getting a Louis Vuitton or a Gucci. Perhaps it gave a measure of cachet to the individual who commissioned it.”

Following El Greco’s death in 1614, he faded into relative obscurity—at least until the end of the 19th century, when modern artists such as Picasso “rediscovered” his oeuvre, Long tells WTTW.

“One painting in our show, a loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Vision of Saint John, is said to be the direct model for Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon at MoMA, one of his most famous proto-Cubist figure paintings,” the curator adds.

The Art Institute acquired a standout work in the show, The Assumption of the Virgin, at the suggestion of Impressionist painter Mary Cassatt in 1906.

A career-altering commission for El Greco, the work—created shortly after his move to Toledo—demonstrates “Renaissance assimilations brought to maturity,” writes Jackie Wullschläger for the Financial Times. “… [T]he eccentric spatial relationships, elongated figures, extreme expressiveness, [herald] a breakthrough to El Greco’s own visionary, instantly recognizable language.”

The 1577–79 composition depicts the Virgin Mary as a “powerful, open-armed Madonna in iridescent silk” who surges “to heaven on a crescent moon, a panoply of luminous angels behind her,” according to Wullschläger.

As Long tells WTTW News, El Greco’s later Toledo works embody the full realization of his distinctive style.

She adds, “There is no one else painting like this, at that time in his lifetime or afterwards.”

“El Greco: Ambition and Defiance” is on view at the Art Institute of Chicago through October 19.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/71/a5/71a50b1c-eb13-4ee3-ba4c-5b7dad7af4d2/default.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bb/60/bb60ed25-885a-48ae-ad5c-18ec7bc5354c/07viewoftoledo_web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)