Elizabeth I’s ‘Idiosyncratic’ Handwriting Identifies Her as the Scribe Behind a Long Overlooked Translation

The Tudor queen wrote in an “extremely distinctive, disjointed hand,” says scholar John-Mark Philo

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/52/8e/528e2c94-50ca-4e5c-ade2-c27f12520c34/testing.jpg)

Elizabeth I’s scholarly prowess was evident throughout her long life. At age 11, she translated a complicated French text called The Mirror of the Sinful Soul as a New Year’s present for her stepmother Catherine Parr, and at age 63, she won plaudits for responding to a Polish ambassador’s criticism with an “improptu rebuke” delivered in scathing Latin.

In the words of the Tudor queen’s chief advisor, William Cecil, “Her Majestie made one of the best [answers], ex tempore, in Latin, that ever I heard, being much mooved to be so challenged in publick, especially so much against her expectation.”

Now, new research is poised to add another accomplishment to Elizabeth’s already impressive résumé: As John-Mark Philo, a literary scholar at the University of East Anglia, reports in the Review of English Studies, annotations found on an early translation of Tacitus’ Annals (a history of the Roman Empire from Tiberius to Nero) match the queen’s “strikingly idiosyncratic” handwriting, suggesting the English queen herself was the work’s author.

Philo happened upon the manuscript while conducting research at London’s Lambeth Palace Library, which has housed the text in question, Tacitus’ Annales, since the 17th century. According to the Guardian’s Alison Flood, he realized the translation’s royal connection after noticing the vellum pages bore watermarks commonly used in the queen’s correspondence and personal papers—among others, a lion, a crossbow and the initials “G.B.”

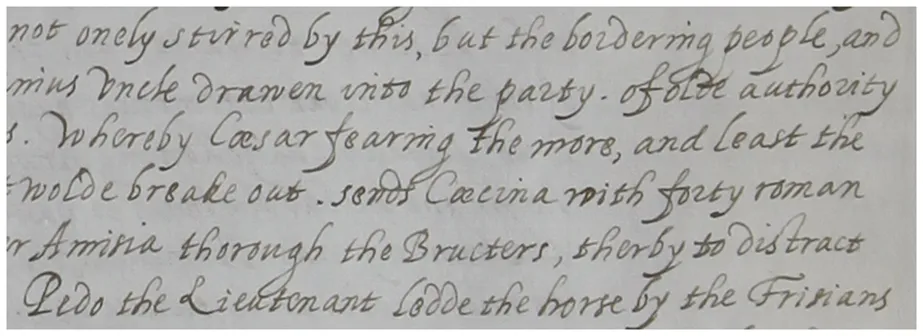

The shared watermarks piqued Philo’s initial interest, but as he tells Flood, the factor “that clinched it for me was the handwriting.” While the translation itself was elegantly copied by a professional scribe (newly identified as a member of Elizabeth’s secretarial staff during the mid-1590s), the corrections and additions scribbled in its margins were penned by what the researcher deems an “extremely distinctive, disjointed hand.”

Per a press release, Elizabeth’s penmanship deteriorated over time, with the speed and sloppiness of her writing rising in direct correlation with the crown’s increasing “demands of governance.” The queen’s “m” and “n,” for instance, essentially became horizontal lines, while her “e” and “d” broke down into disjointed strokes.

“The higher you are in the social hierarchy of Tudor England, the messier you can let your handwriting become,” says Philo in a University of East Anglia statement. “For the queen, comprehension is somebody else’s problem.”

Elizabeth’s handwriting was so difficult to read, Philo adds, that letters sent in her later years were often accompanied by a note from an aide stating the 16th-century equivalent of “Sorry, please find a legible copy here.”

Historians have long known of the queen’s interest in translation and specifically the work of Tacitus, a Roman senator and historian active during the first century A.D. His Annals outlined the rise of the first Roman emperor, Tiberius, revealing the debauchery and corruption that ran rampant in the early days of the empire. Writing in Observations on the Reign of Queen Elizabeth, contemporary John Clapham even said, “She took pleasure in reading of the best and wisest histories, and some part of Tacitus’ Annals she herself turned into English for her private exercise.”

Still, Sarah Knapton reports for the Telegraph, scholars had failed to find the Tacitus translation cited by Clapham until now, and the newly identified text marks the “first substantial work” attributed to the Tudor queen to emerge in more than a century.

Although the translation includes slight errors in grammar and meaning, as well as certain omissions, Philo tells Knapton, “We know she was studying one of the most shrewd political thinkers of antiquity, and engaging with this material on a very deep level.”

According to the statement, the manuscript’s tone and style is characteristic of the Tudor queen: Its author provides a sense of Tacitus’ dense prose and “strictly follows the contours of the Latin syntax at the risk of obscuring the sense in English.” And as Flood notes for the Guardian, the passage selected for translation offers an additional hint of the scholar’s identity; a scene involving a general’s wife, Agrippina, calming her husband’s troops bears striking parallels to Elizabeth’s address at Tillbury before troops preparing to stave of the Spanish Armada.

“I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too,” the queen famously told the soldiers in July 1588.

“It is hard not to wonder what Elizabeth made of Agrippina, ‘who,’ as Elizabeth translates it, being a woman of a great courage, ‘tooke upon hir some daies the office of a Captaine’ and is able to rouse the troops successfully,” says Philo in the statement. “It is not unreasonable to assume that Agrippina may have appealed to the same queen who addressed the soldiers at Tilbury, and who had deliberately represented herself as placing the importance of addressing her troops in person above her personal safety.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)