I.M. Pei Dies at 102 Years Old. Here Are Some of His Essential Buildings

The architect changed the way the world sees itself

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f4/2f/f42f2173-a354-402e-bbda-199c7b89c0cc/eg5a54.jpg)

Ieoh Ming Pei was born in China in 1917 and permanently migrated to the United States after studying architecture there. During World War II, he made a brief career detour when he advised the National Defense Resource Council on the most effective way to bomb buildings and bridges in Germany and Japan. But after the war, he returned to architecture, where he focused on modernistic structures in urban areas.

Geometric shapes, carefully planned public spaces, and use of glass and concrete soon became his trademark. As one of architecture’s most visible and awarded figures, he’s racked up plenty of fans in and outside of his profession. “He has refused to limit himself to a narrow range of architectural problems,” noted the jury in their citation for Pei’s 1983 Pritzker Prize, the industry’s highest honor. "His versatility and skill in the use of materials approach the level of poetry.”

Pei himself approaches poetry in his own words about architecture. “Architecture is the very mirror of life,” he told Gero von Boehm. “You only have to cast your eyes on buildings to feel the presence of the past, the spirit of a place; they are the reflection of society.”

The famed architect recently celebrated his 100th birthday, and cities around the world whose skylines have been transformed by his unmistakable designs are considering his legacy. Celebrate Pei with a trip through his career—and some of his most iconic buildings.

Mesa Laboratory - Boulder, Colorado

Pei is known for drawing from regional and historic influences in his work. One striking example is the 1966 Mesa Laboratory of the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado. Pei found inspiration in the Ancestral Pueblo cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde, creating a building made of concrete that appears as if it's almost growing out of the landscape in front of a vista of foothills and plains. The nine-inch-thick concrete walls saved construction money, but also presented a logistical challenge; according to the NCAR website, the construction superintendent compared building the structure to “building a dam.” The original project included a third tower, but budget cuts got in the way. The loss was a disappointment to Pei who said that the final southerly tower would have anchored the project, "tapping the soil" like a Mesa Verde structure.

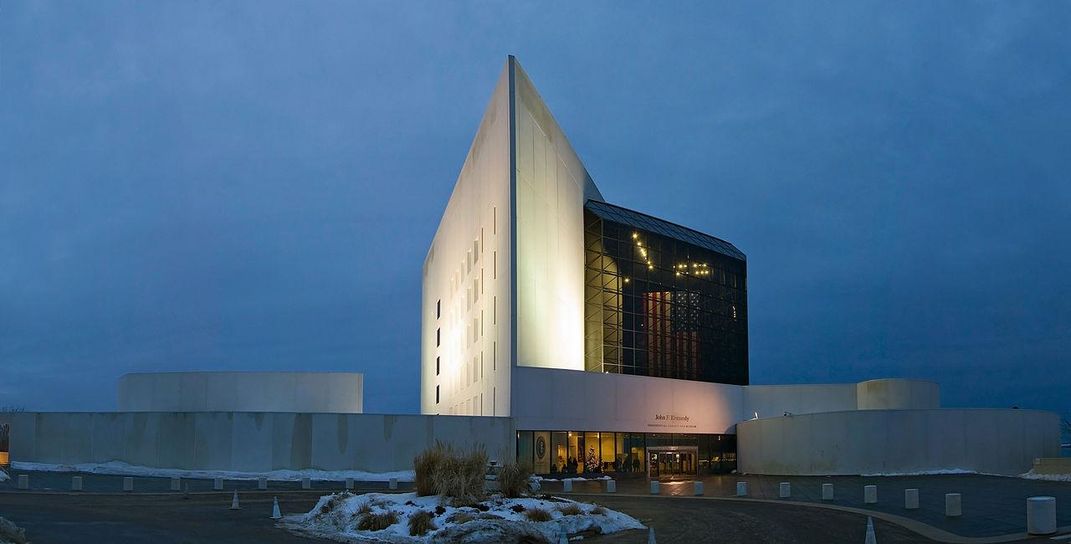

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum - Boston

After JFK’s assassination, a group of his friends and family members spent months trying to decide who should design his library. Pei, a young and then relatively obscure architect, attracted special interest from Jacqueline Kennedy, who liked his modesty and his creativity. “He didn’t seem to have just one way to solve a problem,” she recalled. But Pei worried about his experience. According to the JFK Library’s website, he told Jacqueline Kennedy that he had not worked on any monumental projects. That would soon change—after a years-long design process that included a site change, the concrete, glass and steel library opened in 1979.

Fragrant Hill Hotel - Beijing, China

Not all Pei designs are modernistic—and not all are beloved. In 1982, a traditionally designed hotel by Pei opened in China. The stately structure, studded with courtyards and garden-like landscapes, reflects elements of Chinese heritage—appropriate, given that the building was commissioned by the Chinese government. But when the building opened, Pei was panned by Chinese people who had expected him to build a less traditional structure. The building has since fallen into disrepair.

Louvre Pyramid - Paris

Pei could be best known as the man who put a glass and metal pyramid in the courtyard of a historic art museum. The world-famous Louvre was having trouble handling traffic, so France’s president commissioned Pei to solve the problem. He responded by digging an underground lobby in the courtyard and placing a modernist pyramid on top. The structure, which opened in 1989, drew mixed reviews because of its mixture of stark urban design with its more classical surroundings: As the New York Times’ Paul Goldberger noted at the time, the opening of the structure coincided with a modernization of the museum that was “as dramatic an event as Mr. Pei’s architecture.”

Museum of Islamic Art - Doha, Qatar

After retiring from his firm in 1990, Pei could have rested on his laurels. Instead, he kept on designing, and in 2008 his Museum of Islamic Art opened in Doha, Qatar. Located on a manmade island, it combines Pei’s architectural signatures with echoes of the mosques and fortresses he visited while designing it. The master has called the museum his last major piece. “I don’t want to forget the beginning,” he told The New York Times’ Nicolai Ouroussoff. “A lasting architecture has to have roots.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)