When Secret Service agent Paul Landis spotted an intact bullet resting on the ledge of a seat in the back of the presidential limousine on the day of John F. Kennedy’s assassination, he reportedly pocketed it to ensure it wouldn’t fall into the hands of souvenir hunters or the press. Accompanying first lady Jackie Kennedy into the Dallas hospital where surgeons fruitlessly tried to save her husband’s life, Landis says he found himself next to the president’s stretcher.

“People were coming in,” he recalls to CNN’s Jake Tapper. “It was chaos. At that moment, I thought, ‘Well, this is the perfect place to leave the bullet. It should be with the president’s body. It’s an important piece of evidence.’” Landis claims he tucked the bullet into a blanket by Kennedy’s left foot, assuming it would be discovered before the president’s autopsy. Haunted by what he’d seen that day in Dallas, he all but forgot about the bullet for the next 50 years.

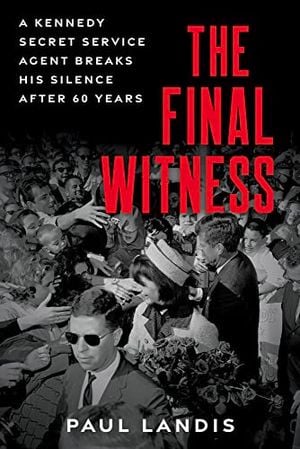

Now 88, Landis is finally sharing his recollections of November 22, 1963. In The Final Witness: A Kennedy Secret Service Agent Breaks His Silence After Sixty Years, out October 10 from Chicago Review Press, he refutes the Warren Commission’s single-bullet theory, which posits that one of the bullets fired that day entered Kennedy’s body from behind, then exited through his throat before striking Texas Governor John B. Connally Jr.’s back, chest, wrist and thigh. This bullet, per the commission, was later found on Connally’s stretcher.

The Final Witness: A Kennedy Secret Service Agent Breaks His Silence After Sixty Years

Paul Landis details his recollections of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963.

Landis believes this “magic bullet,” as it’s nicknamed by skeptics in recognition of its seemingly improbable trajectory and pristine condition, only struck Kennedy—and that it’s the same one he found in the limousine and left on the president’s stretcher. The projectile may have rolled onto Connally’s stretcher at a later point, leading authorities to link it to the governor’s injuries, Landis tells the New York Times’ Peter Baker. If this theory is correct, it could indicate that Connally was hit by a different bullet—perhaps even one fired by someone besides Lee Harvey Oswald, who would’ve had to fire three shots consecutively and accurately in just a few seconds.

“If what [Landis] says is true, which I tend to believe, it is likely to reopen the question of a second shooter, if not even more,” says James Robenalt, a lawyer and historian who consulted with Landis on the book, to the Times. Landis himself has long agreed with the official explanation that Oswald acted on his own. “At this point,” however, he tells the Times that he’s “beginning to doubt myself. Now I begin to wonder.”

Some scholars are skeptical of Landis’ account, which differs from two written statements he provided to authorities shortly after the shooting. Speaking with People’s Liz McNeil and Virginia Chamlee, Steve Gillon, author of a 2010 book on the assassination, says, “Historians are always taught to believe contemporaneous accounts over memory, which fades over time. It is difficult to accept that Landis remembers things 60 years later that he did not remember at the time. There are too many contradictions for this account to be credible.”

On the day of Kennedy’s death, Landis was a 28-year-old Secret Service agent assigned to protect the first lady. He was riding on the running board of a black Cadillac behind the presidential limousine when a shot rang out. According to a November 27, 1963, statement, Landis “heard a second [shot] and saw the president’s head split open.” A few days later, on November 30, he said his “immediate thought was that the president could not possibly be alive after being hit like he was.” At the hospital, Landis stayed “right next to Mrs. Kennedy” until the president’s body was removed in a coffin. Per the Times, he remained in Jackie’s employment for the next six months but then decided to leave the Secret Service. He spent the next decades working in real estate, house painting and manufacturing, rarely discussing what he’d witnessed.

As Landis tried to forget the assassination, public interest in—and debate over—the president’s death mounted. The Warren Commission, which was established by Kennedy’s successor, President Lyndon B. Johnson, to investigate the assassination, released its findings in September 1964, reporting that Oswald had fired three shots at the president from a sixth-floor window in the Texas School Book Depository.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e9/40/e9400ecc-8e84-4eb5-8500-16ac42b69c9a/jfkwhp-st-a19-25-62.jpg)

The 888-page report suggested that one of the bullets missed the president, while another struck him before continuing on to wound Connally. A third bullet hit Kennedy’s head, inflicting a fatal injury. The commission also concluded that both Oswald and Jack Ruby, the nightclub owner who murdered Oswald two days after the assassination, acted alone, clearing the Soviet and Cuban governments, the Secret Service, the FBI, the CIA, and American organized crime syndicates of involvement in a conspiracy to kill Kennedy.

Initially, the public largely accepted the commission’s report, with 87 percent of Americans polled by Gallup agreeing that Oswald shot the president. But criticism of the commission mounted over the next decade or so, peaking in the late 1970s with the release of the Zapruder film, a 26-second video capturing the shooting in graphic detail, and a congressional report that drew on audio recordings, now believed to be questionable, to conclude that a second shooter took aim at the president from a grassy knoll.

As Gillon wrote for History.com in 2017, “There were now two conspiracies: the conspiracy to assassinate the president and, potentially, an even larger and more insidious conspiracy among powerful figures in government and the media to cover it up.” Despite the release of 99 percent of the once-classified government documents related to the assassination, none of which offered a smoking gun refuting the commission’s findings, a 2017 FiveThirtyEight poll found that 61 percent of adult Americans believe that more than one person was involved in Kennedy’s death.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/96/ab/96abe96a-f6aa-4953-8e80-c2a9aa146200/1920px-bullet_found_on_stretcher_at_parkland_memorial_hospital_-_nara_-_305144_page_7.jpeg)

It was only in 2014, when Landis finally started reading about the assassination, that he realized the official account didn’t match up with his recollections. The 1967 book Six Seconds in Dallas: A Micro-Study of the Kennedy Assassination, for instance, described a bullet being found on Connally’s stretcher.

“They showed a picture [of the bullet] in the book, and my reaction was, ‘Well, wait a minute. That’s the bullet that I put on President Kennedy’s stretcher,’” Landis tells People. “And that triggered some thoughts, and I wondered what to do. How do I straighten this all out?”

After consulting former Secret Service director Lewis Merletti, Landis decided to write a book about his memories of the assassination. “In the intervening seven years, he struggled with his conscience,” writes Robenalt for Vanity Fair. “His guilt, in my estimation, stemmed in part from a creeping concern that others might accuse him of having done something wrong by moving the bullet.” Robenalt, who met with Landis more than a dozen times in the past year at the suggestion of their mutual publisher, speculates that the retired agent was also worried that readers would criticize him for not coming forward to correct the record sooner.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2f/8e/2f8ec623-7aad-433d-9ec1-da40af76dd48/jfkwhp-ar8255-2d.jpg)

In Landis’ telling of the assassination, he noticed the bullet, which was lodged into the seam of a limousine seat’s cushion, while helping Jackie out of the car. He brought the projectile into the hospital, planning to hand it over to a supervisor, “but in the confusion instinctively put it on Kennedy’s stretcher instead,” according to the Times. An engineer at the hospital later found the bullet while moving Connally’s stretcher, though he was unsure whether it came from the governor’s stretcher or one unrelated to the assassination. The circumstances of the bullet’s discovery led the Warren Commission to argue that it was responsible for both Connally’s injuries and the president’s neck wounds—a verdict supported by more recent forensic tests proving that a single bullet could indeed cause all of this damage.

In the days after Kennedy’s death, Landis offered written testimony of what he’d seen in Dallas, omitting mention of moving the bullet. “He was totally sleep deprived and was still required to work, and was suffering from severe PTSD,” Robenalt tells BBC News’ Kayla Epstein. “He forgot about the bullet.” Though Landis says he planned to share the full story with the Warren Commission, its members never called him to testify.

The implications of Landis’ account differ depending on who one asks. In Vanity Fair, Robenalt argues that his story suggests a bullet “lodged superficially in the president’s back before being dislodged by the final blast to his head” and becoming embedded in the seat. If this were the case, a separate bullet must have hit Connally, meaning the shooter had to fire two shots within less than 2.25 seconds of each other—a challenging but not impossible task based on later forensic recreations conducted by the FBI. “A second shooter must be considered,” Robenalt writes.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a0/22/a0228a35-e7d6-4772-8bf1-ce4327b1f1b4/jfk_limousine.png)

Clint Hill, a former colleague of Landis’ who famously jumped onto the back of the presidential limousine in hopes of saving the Kennedys’ lives, is more critical of Landis’ story. Hill tells KFYR’s Justin Gick that Landis originally shared a different anecdote with him in 2014, saying he’d “found a bullet, almost completely intact, which he picked up. He put it in his pocket, and he said he brought it into the emergency room and dropped it off on a gurney in the hallway,” not Kennedy’s stretcher specifically. “It couldn’t have happened the way he now tells the story,” Hill adds.

Gerald Posner, author of Case Closed: Lee Harvey Oswald and the Assassination of JFK, is similarly skeptical. Speaking with CNN’s Michael Smerconish, Posner says Landis is “absolutely sincere, and he believes” his story. But Posner points out that “we have many instances, not just with the Kennedy assassination, … in which individuals who are witnesses to traumatic events later read accounts or they talk to other people, they see documentaries, and their new memories become part of their old memories.” He adds, “Sixty years later, [Landis is] now telling us how his memory got better, and we all know, unfortunately, that’s just not how it happens.”

Landis, for his part, views his new book as a form of catharsis. As he tells People, “It is just a different level of relief for me [after] I carried this with me for so long.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/20/b8/20b8a900-f424-496b-aed1-0c9ee23c20a4/lbj_taking_the_oath_of_office.jpeg)

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(1550x1100:1551x1101)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/49/00/49002efe-633c-4c50-9286-9302b773b286/gettyimages-615320656.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)