Researchers Excavating Norwegian Viking Ship Burial Find Remnants of Elite Society

Archaeologists discovered traces of a feast hall, farmhouse, temple and 13 additional burial mounds

:focal(566x326:567x327)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/62/f2/62f2ed4e-7a14-475d-a8d9-ecd1bf0f732f/remains_of_a_viking_ship.gif)

This summer, Norwegian archaeologists embarked on an ambitious, tricky venture last attempted in the country more than 100 years ago: the full excavation of a Viking ship burial.

In May, Norway’s government dedicated roughly $1.5 million USD toward excavating the Gjellestad ship—a time-sensitive project, as the vessel’s wooden structure is threatened by severe fungal attacks. After archaeologists set up shop in a large tent on a farm in southeastern Norway, they commenced the painstakingly slow process of digging, reported Christian Nicolai Bjørke for Norwegian broadcaster NRK in August.

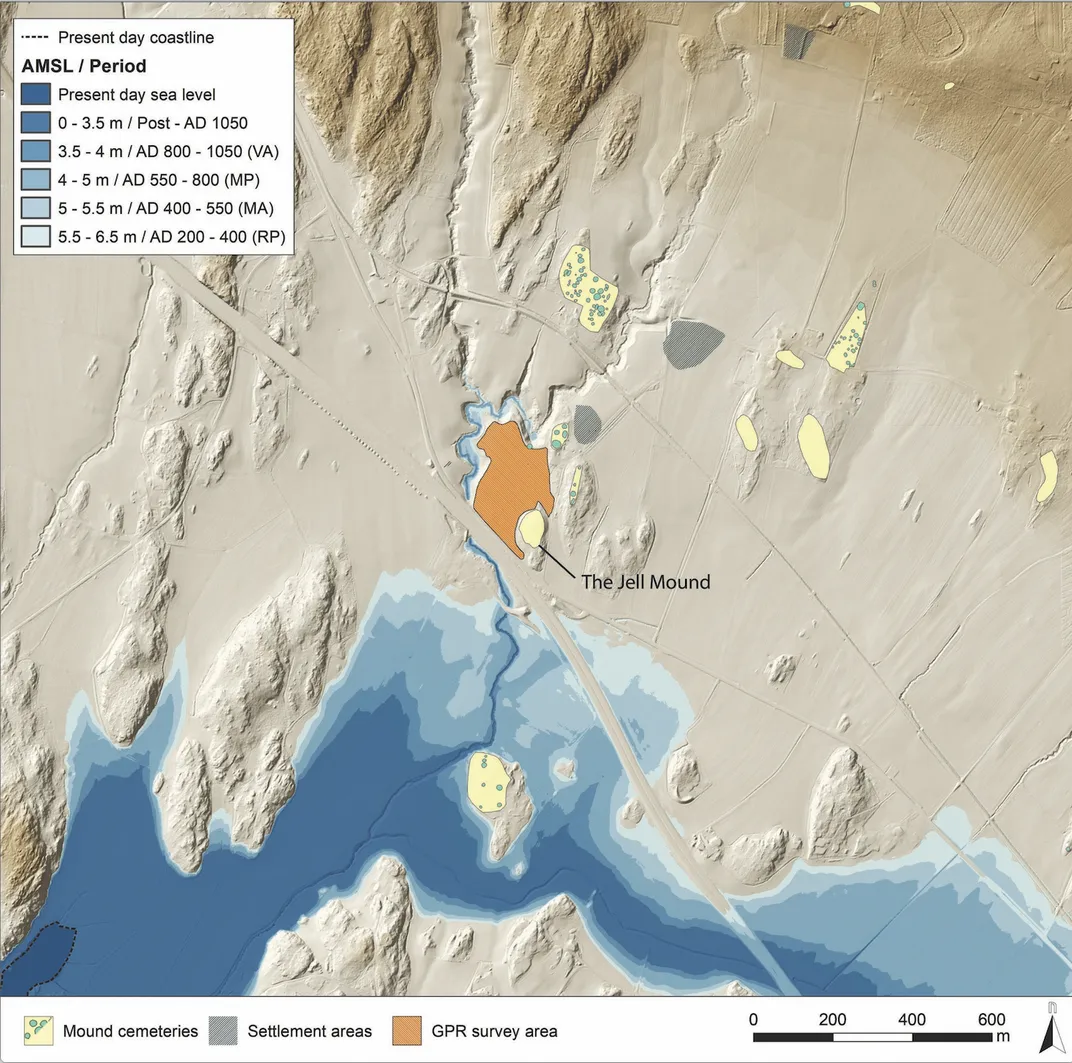

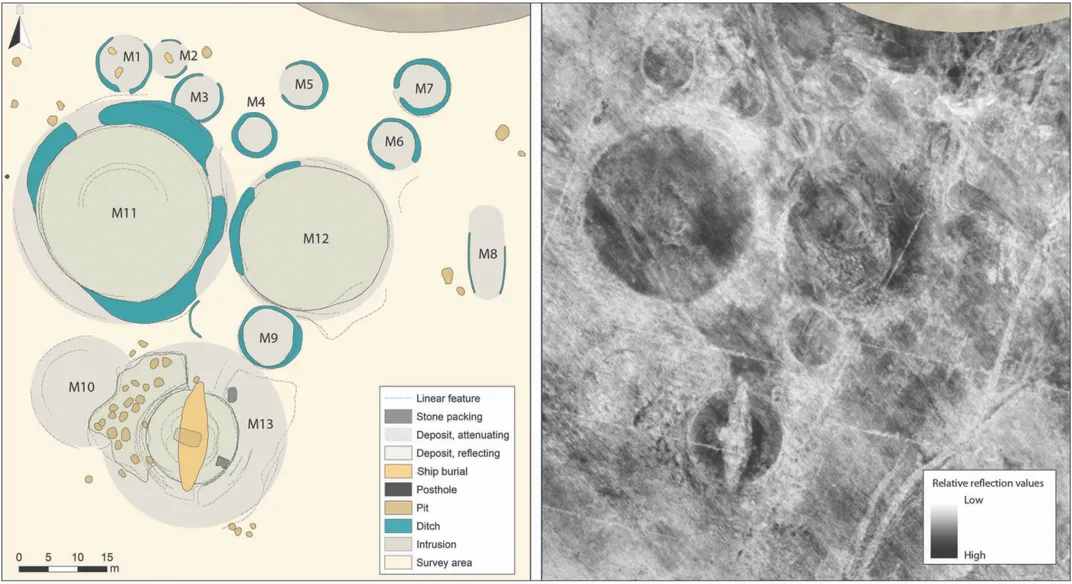

Now, with the dig set to continue through December, new research continues to shed light on the burial site’s history. In a study published this week in the journal Antiquity, researchers from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU) revealed that the Viking ship wasn’t buried by itself. Per a NIKU statement, ground-penetrating radar (GPR) identified a feast hall, farmhouse, temple and traces of 13 additional nearby burial mounds—all finds that indicate the site once served as a crucial space for gathering, feasting, governing and burial.

Researchers using GPR discovered the 60-foot-long vessel hidden just 20 inches below the surface of a farming field in the fall of 2018. The ship burial likely served as the final resting place for a powerful Viking king or queen who died more than a thousand years ago, reported Andrew Curry for National Geographic at the time.

The team’s latest finds indicate that the Gjellestad site was active during a key period in Scandinavian history: between the political tumult following the collapse of the Roman Empire in the fifth century A.D. and the rise of the Vikings in Norway in the early ninth century.

Archaeologists found the buried vessel beneath flat farmland adjacent to the Jell Mound, the second-largest earthen funeral mound in Scandinavia. The Viking ship was buried around 800 A.D., while the Jell Mound dates to the beginning of the Late Nordic Iron Age (about 550 to 1050 A.D.).

“We suggest that the site has its origins in an ordinary mound cemetery, which was later transformed into a high-status cemetery represented by monumental burial mounds, hall buildings and a ship burial,” the researchers write in the study.

In the statement, lead author Lars Gustavsen adds, “The site seems to have belonged to the very top echelon of the Iron Age elite of the area, and would have been a focal point for the exertion of political and social control of the region.”

Some of the newly discovered burial mounds detailed in the NIKU study measure 98 feet wide, reports Mindy Weisberger for Live Science. Archaeologists used GPR to identify two large circular mounds, seven smaller mounds situated a bit to the north and four rectangular “settlement structures.” One of the largest buildings resembles other known Viking feasting halls.

Taken together, the extensive network of burial and community gathering sites at Gjellestad indicates that a wealthy society dwelled in the region for generations. What’s more, the Viking-era ship burial builders were eager to affirm their political influence by creating a ship burial on top of century-old mounds—the “ultimate expression of status, wealth and connection in Iron Age Scandinavia,” according to the paper.

As Gustavsen tells Live Science, “We believe that the inclusion of a ship burial in what was probably an already existing—and long-lived—mound cemetery was an effort to associate oneself with an already existing power structure.”

The partially intact Gjellestad ship burial is one of the few known to survive until the present day. Historical records indicate that investigators dug up part of the ship in the 19th century, Gustavsen tells CNN’s Harry Clarke-Ezzidio. At the time, locals unaware of the vessel’s significance burned many of its wooden remains, leaving behind only part of the ship’s wooden frame.

In the mid-20th century, farmers unwittingly installed a drainage pipe on top of the ship. The pipe leaked air down into the wooden structure and allowed destructive fungi to proliferate, Bjørke reported for NRK in September. Now, the government is hastening to finish excavations before the ship can rot any further.

“It’s a unique opportunity, it’s just a shame that there is so little left of it,” Gustavsen tells CNN. “What we have to do is use modern technology and use it very carefully. By doing that, we're hoping that we can capture something from that ship, and be able to say something about what type of ship it was.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)