Exhibit of Art by Guantánamo Prisoners Prompts Pentagon Review

The Department of Defense has halted transfers of artworks by detainees

The fences that surround Guantánamo Bay are covered with tarp, blocking prisoners’ view of the sea that surrounds the detention center. But in 2014, in preparation for a hurricane that was heading toward Cuba, prison authorities removed the tarps. “It felt like a little freedom,” Mansoor Adayfi, a former Guantánamo detainee, wrote in an essay that was published in the New York Times. “The tarps remained down for a few days, and the detainees started making art about the sea.”

Selections of the prisoners’ artworks are now on display at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in Manhattan, forming an exhibition titled “Ode to the Sea.” According to Jacey Fortin of the New York Times, news of the exhibition, which opened October 2, has now attracted the attention of the Pentagon, which is currently reviewing the way it handles prisoners’ art.

Major Ben Sakrisson, a Pentagon spokesman, tells Fortin that the Department of Defense has halted the transfer of detainees’ artwork while the review is pending, but that it will not pursue pieces that have already been released.

“[I]tems produced by detainees at Guantánamo Bay remain the property of the U.S. government,” Sakrisson tells Fortin.

In a separate interview with Carol Rosenberg of the Miami Herald, Sakrisson also expressed concern over a note on the exhibition’s website, which states that art by former prisoners who have been cleared by military tribunals is available for purchase, saying, “[Q]uestions remain on where the money for the sales was going."

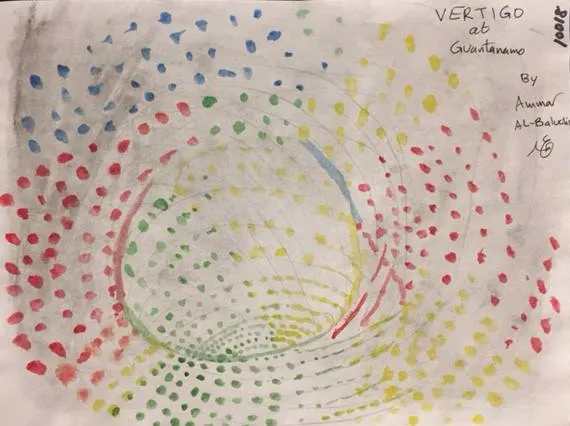

“Ode to the Sea” includes 36 pieces by eight “enemy combatants,” some of whom are still prisoners, some of whom have been cleared by military tribunals and released. Though a number of the paintings feature the hallmark subjects of still life (flowers, glassware, fruit), many are preoccupied with the beauty and unpredictability of the sea.

A piece by Djamel Ameziane, a refugee from Algeria, was detained in Guantánamo Bay for more than 11 years, shows a shipwrecked boat toppled on its side. Another by Muhammad Ahmad Abdallah al Ansi, who was suspected of working as a bodyguard for Osama bin Laden but cleared by a tribunal last year, features the Statue of Liberty standing tall against a backdrop of vibrant blue waters. Moath Hamza Ahmed al-Alwi, who has been accused of associating with Al Qaeda but has never been charged, created elaborate cardboard models of 19th-century ships.

The artworks were loaned to John Jay by the detainees’ lawyers, who were given the pieces as gifts or for safekeeping. Erin Thompson, a professor of art crime and a curator of the exhibition, tells Reiss that she believes “that to prevent terrorism we need to understand the minds of terrorists and the minds of people wrongly accused of terrorism. So this art is really an invaluable window into the souls of people we need to understand.”

Rosenberg of the Miami Herald notes that attorneys for Guantánamo detainees have reported that while their clients have been allowed to continue making art, they are now able to keep only a limited number of pieces. Inmates have also been informed that their work will be incinerated if they are ever released from the detention center, Rosenberg reports.

Thompson, the John Jay curator, has launched a petition in protest of the crackdown on detainees’ art. “Taking away [prisoners’] ability to find and create beauty and communicate with the outside world through their paintings, drawings, and sculpture is both incredibly petty and incredibly cruel,” the petition reads. To date, it has been signed by nearly 1,500 people.