This Exhibit Asks You to Caption Photos of People Caught in Mid-Sentence

National Portrait Gallery exhibit features snapshots of Muhammad Ali, John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr.

:focal(289x251:290x252)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/95/ff/95fff912-312a-4283-8b9d-0918f860621f/ali.jpg)

On December 7, 1970, journalists and photographers surrounded boxer Muhammad Ali at a New York City press conference held just before his fight against Argentina’s Oscar Bonavena.

Ali had a way with words, and photographer Garry Winogrand found the competitor’s catchy lines—in addition to advertising the upcoming match, he was advocating to make the fight accessible to people who couldn’t afford tickets—to be the perfect catalyst for his Guggenheim Fellowship project: capturing “the effect of the media on events.”

Winogrand started snapping.

One photo in particular stuck in his mind. Six men in coat and ties shove their microphones as close to Ali’s face as possible, trying to absorb every word out of the heavyweight champion’s mouth. Eager reporters and photographers stand behind a restricted rope, watching other interviewers circle Ali.

In the midst of the frantic press conference, a man in a striped button-down shirt sits crouched below the boxer. He’s laughing, his eyes squinting and his mouth cracking into a wide smile.

What is Ali saying? And just what is so funny?

An ongoing exhibit at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery attempts to answer these questions, encouraging visitors to fill in the unheard words of history’s missing scripts.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e0/e0/e0e0182d-a768-4681-a873-1b6e420807f1/angela.jpg)

On view through March 8, “In Mid-Sentence” features 26 black-and-white photographs of people frozen in the act of communication. Taken between 1936 and 1987, the images depict pivotal moments—intimate confessions, speeches to the nation, confrontations, classroom exchanges and even a joke—rendered silent by the camera’s gaze. By placing the photographs in their historical context, the show gives visitors the chance to meditate on what occurs in the midst of speaking, including what might be lost, unheard or even unfinished.

“It’s looking at this concept of communication, whether public, private or in between, and trying to listen in on some of these conversations that may tell us a lot more about American history,” says Leslie Ureña, the gallery’s associate curator of photographs.

“In Mid-Sentence” divides its snapshots into four categories: “In the Public Eye,” “Teaching and Learning,” “Public/Private,” and “Just Between Us.” While some images appear to be one-on-one portraits, none of the shots are truly private; in each case, subjects were aware of the photographer’s presence in the room.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/82/e2/82e269ed-e620-49d6-9540-2eba585f9a4b/jfk.jpg)

Three selections from Winogrand’s 15 Big Shots portfolio anchor the exhibit. In one snapshot, the photographer depicts John F. Kennedy addressing the crowd at the 1960 Democratic National Convention. Though the image finds Kennedy with his back to the camera, a TV screen at the bottom of the scene reveals what people watching at home saw when they tuned in to the future president’s speech. Winogrand simultaneously captures both the real-life and virtual versions of Kennedy gesturing at the crowd, drawing visitors’ attention not to his words, but his actions. Through the tiny television, viewers can see Kennedy’s face, as well as how reporters captured his speech.

Thanks to the newfound intimacy offered by television, Kennedy became a friendly face instantly recognizable to people across the country.

“Part of [the exhibit] was this idea of how we communicate,” says Ureña, “not only things that are meant to be very, very public speeches … but how we consume these muted interactions that are meant to impart knowledge in a more private way.”

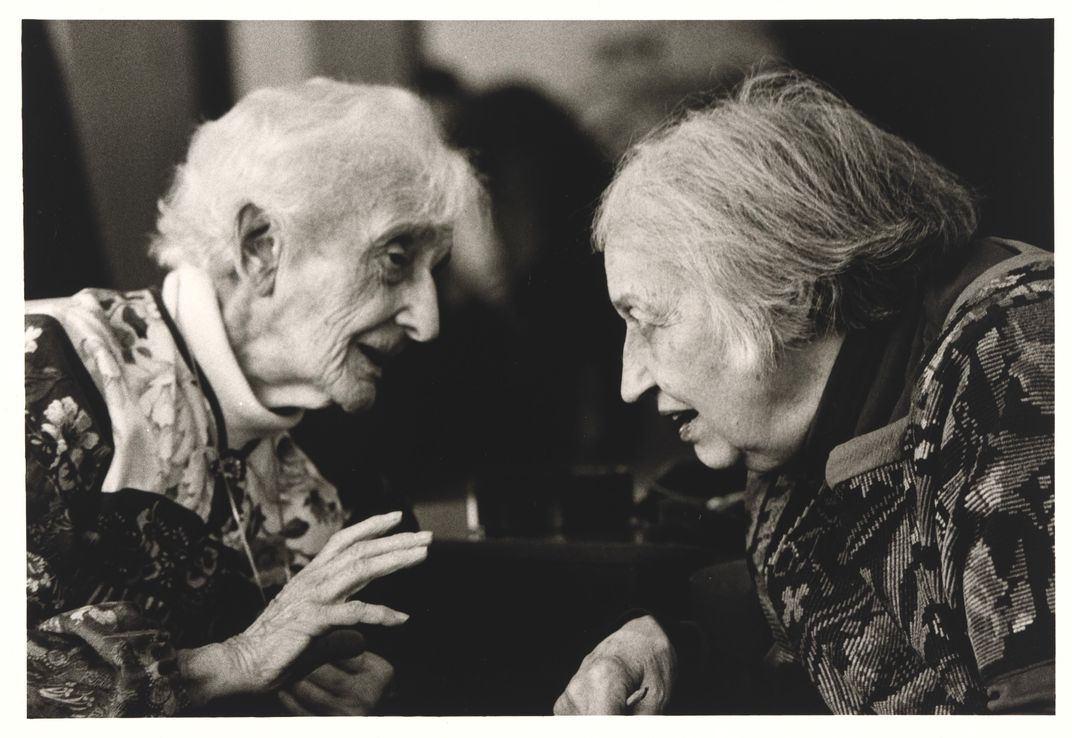

“In Mid-Sentence” draws on different elements of the public and private sphere. In a 1957 snapshot, for example, Althea Gibson, a groundbreaking African American athlete who crossed racial barriers in tennis, holds a paddle racket during a lesson with young people from her childhood neighborhood—a moment of passing down knowledge to future generations. Catharine Reeve’s 1982 image of a conversation between photographers Lotte Jacobi and Barbara Morgan, meanwhile, shows less accessible details; the two were attending a seminar about women photographers at Northwestern University, and Jacobi had expressed her annoyance over Reeve taking “so many pictures” right before the photographer captured the intimate exchange.

To choose 26 photos for the exhibit, Ureña sifted through some 11,000 images in the museum’s online collection. But the archival deep dive didn’t stop there. Throughout the exhibit, visitors will find five different video clips matched to the exact moment of communication frozen in the accompanying images.

This supplement, available via a video kiosk, contextualizes five famous candid snaps with in-the-moment visuals and sound, according to Ureña. Snippets from attorney Joseph Welch’s “Have you no sense of decency?” speech, directed toward Joseph McCarthy during a 1954 congressional hearing on the senator’s investigation of the U.S. Army, as well as Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, are among the exhibit’s video aids, reports the Washington Post’s Mark Jenkins.

Contrasted with today’s “selfie-conscious” world, “In Mid-Sentence” invites visitors to explore how earlier generations interacted with the camera.

“It gives us a sense of how we interact with ourselves, the public and the private realms,” says Ureña. “… It’s this aspect of how we look at these photographs and what we ask of them … and then peeling away the layers until we get as close as possible to the actual conversation.”

“In Mid-Sentence” is on view at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery through March 8.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/37340836_1862108597212824_3071431907662102528_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/37340836_1862108597212824_3071431907662102528_n.jpg)