Spotlighting the Forgotten Women of the Surrealist Movement

A new show reveals how Frida Kahlo, Meret Oppenheim and other women artists probed questions of femininity, autonomy and politics

:focal(1192x731:1193x732)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b2/16/b2161b8f-d5b3-4563-9b50-81afe70a8cfd/schirn_presse_fantastische_frauen_installationsansicht_miguletz_5.jpg)

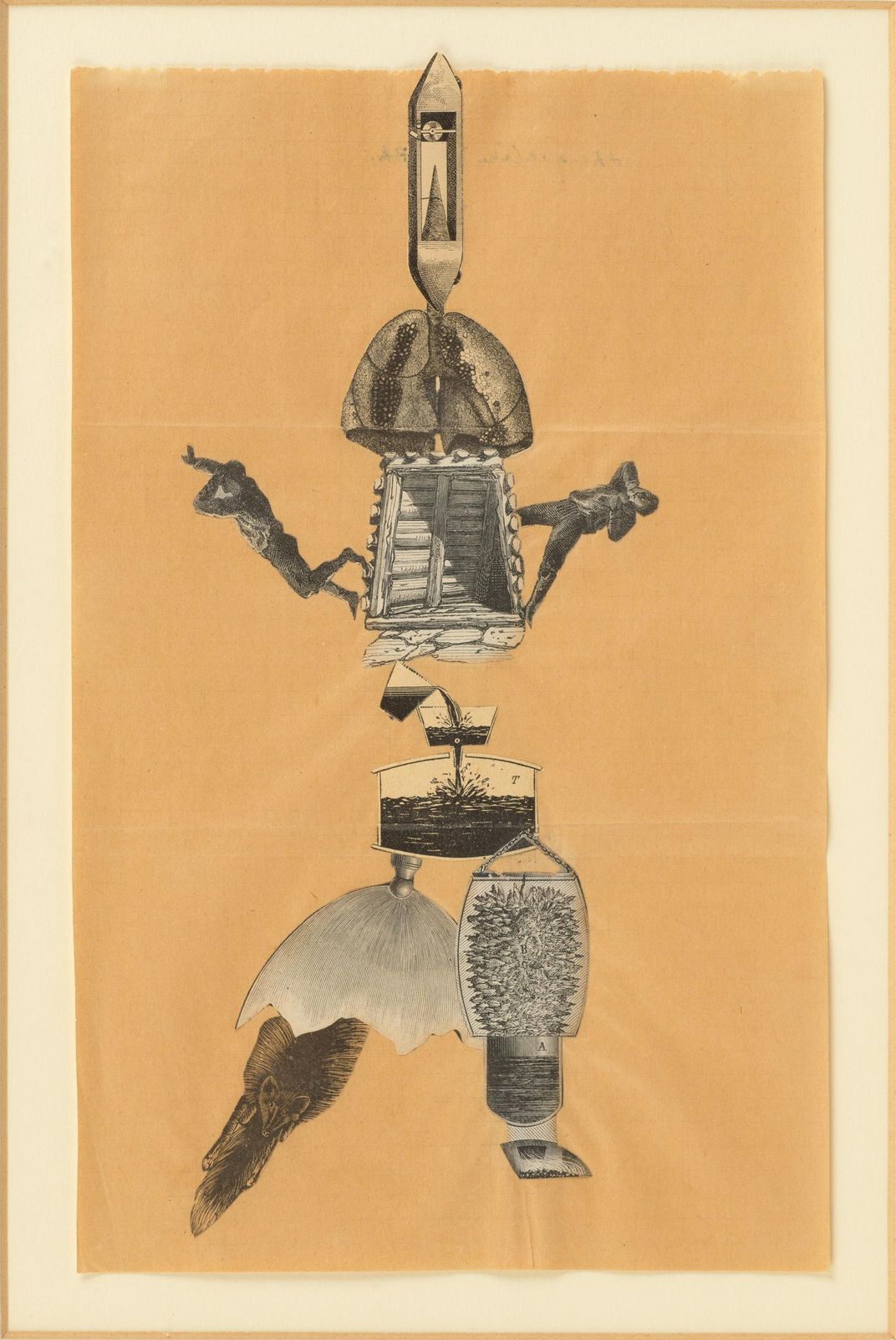

To begin the game of Exquisite Corpse, an artist draws a head on a folded piece of paper. After the individual turns the page over to hide their work, they pass the paper along to the next contributor, who draws a torso. Participants repeat the process until the mismatched figure is complete.

Among Surrealist circles convened between the 1920s and ‘60s, the result of this activity was often a strange, unpredictable character made up of disparate elements like a stack of eyes, constellations and a carafe of coffee. But Exquisite Corpse and similar games were about more than just the end product. They were also designed to inspire creative processes, activate the subconscious and increase group cohesion—familiar aspirations for Paris’ Surrealist artists, who frequently met in cafés to discuss politics and psychoanalysis.

Originally dominated by men, the Surrealist movement had expanded its membership to women by the 1930s. Today, however, these female artists remain little-known, overshadowed by such individuals as Salvador Dalí, René Magritte and Max Ernst.

A new survey of Surrealism’s influential female figures strives to help rectify this imbalance. Titled “Fantastic Women: Surreal Worlds From Meret Oppenheim to Frida Kahlo,” the exhibition, on view at the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, features some 260 works of art by 34 artists from 11 countries. The women represented include the two who lend the show its title, Louise Bourgeois, Maya Deren, Ithell Colquhoun and Dora Maar, among others.

“To this day, the names and works of the huge number of important women artists throughout the world are missing in many reference guides and survey exhibitions on Surrealism,” writes curator Ingrid Pfeiffer in an accompanying publication quoted by artnet News’ Kate Brown. “The reasons for this are many, including the endless repetition of an outdated canon in spite of recent research—a problem which pertains to art history in general.”

One of the better-known Surrealists highlighted in “Fantastic Women” is Meret Oppenheim, creator of Object, a sculpture of a teacup sitting on a saucer beside a spoon. The catch? All of this dinnerware is covered in speckled brown fur. Object, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, exemplifies the Surrealists’ desire to bring “everyday things into unlikely alliance,” sparking meditation by placing the mundane in a new light. The original Object sculpture doesn’t appear in the Schirn exhibit, but the show does features similarly thought-provoking works by Oppenheim, including Venus Primitive and the painting Daphne and Apollo, which shows the eponymous river nymph and Greek god mid-metamorphosis.

Women initially entered Surrealist circles as subjects or muses. Oppenheim, for instance, posed nude beside a printing press in a famous photograph for Man Ray. But as the Schirn exhibit reveals, women artists soon became active participants in a movement that celebrated subversion.

Surrealist women’s works play with viewers’ expectations by showing a flipped perspective. Instead of allowing the male gaze to dictate their creations, these artists completed self-portraits or, in other words, images of women looking at themselves rather than men looking at women. One such painting by Leonora Carrington embodies the contrast between societal expectations and female emancipation by placing wild animals—thinly veiled allusions to the artist’s own desire for freedom—in a claustrophobic domestic setting.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0c/2f/0c2fd37c-16d3-4b27-b3de-a7928e09aa5c/schirn_presse_fantastische_frauen_installationsansicht_esra_klein.jpg)

“I didn’t have time to be anyone’s muse. … I was too busy rebelling against my family and learning to be an artist,” Carrington once said, per the museum’s “digitorial” on Surrealism.

Other paintings subvert expectations by showing a strong female guide leading a man, or by using collage to place things where they don’t belong. One piece by Toyen, an androgynous pseudonym for Czech painter Marie Čermínová, depicts a figure in a doorway with a face pasted over its pelvis. And in Jane Graverol’s collage The Prosperity of Vice, a female figure sits atop a bird, a classic symbol of freedom. But in this case, the bird is cut from an image of tank treads.

The show also features Frida Kahlo self-portraits that highlight the famed artist’s relationship with the United States and Mexico. Kahlo exhibited her work in Europe for the first time in 1939; over the following decade or so, many European artists moved to Mexico City, making the Latin American metropolis a new hub of artistic activity.

“Seeing them together, we gain better insight into the international network, the incredible diversity and the impressive independence of both the better and lesser-known women artists of Surrealism,” says Pfeiffer in a statement. “After all, Surrealism was a state of mind rather than a style.”

“Fantastic Women: Surreal Worlds From Meret Oppenheim to Frida Kahlo” is on view at the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt through May 24, 2020.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7e/bd/7ebd8f44-fb53-45ad-ac04-2edd41330cd0/schirn_presse_leonora_carrington_self_portrait_1936-38.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c9/84/c9843d33-7a38-4325-8f39-f44605398385/schirn_presse_fantastische_frauen_bridget_tichenor_los_surrealistas_1956.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1b/b4/1bb4c65d-64f1-4e64-845f-e7091d765724/schirn_presse_fantastische_frauen_marie_toyen_der_paravent_1966.jpg)