London Library Spotlights Nazi Persecution of the Roma and Sinti

The Roma and Sinti’s wartime suffering “isn’t necessarily a subject that people know that much about,” says the curator of a new London show

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bd/ff/bdffb97f-284d-417a-947d-0634c9853098/roma_or_sinti_girl_imprisoned_in_auschwitz_pictures_taken_by_the_ss_for_their_files_wiener_holocaust_library_collections_copy.jpg)

During World War II, the Nazis persecuted and murdered as many as 500,000 European Roma and Sinti deemed “racially inferior.” Now, a new exhibition at the Wiener Holocaust Library in London seeks to explore these individuals’ experiences before, during and after the war, drawing attention to a “little-known” chapter of Holocaust history.

“Even if people are aware that the Nazis targeted Roma as well as Jews, it isn't necessarily a subject that people know that much about,” Barbara Warnock, curator of “Forgotten Victims: The Nazi Genocide of the Roma and Sinti,” tells Al Jazeera’s Samira Shackle.

Originally hailing from India, the Roma and Sinti appeared in almost every European country’s records by the end of the 15th century. Although the Nazis collectively referred to them as “Gypsies,” the Roma and Sinti actually represent two distinct groups distinguished by their traditions, dialect and geographic location. Per the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the term “Gypsies”—now considered discriminatory—arose from the mistaken belief that Roma and Sinti people came from Egypt.

An estimated 942,000 Roma and Sinti lived in German-occupied territory at the start of WWII. According to Shackle, the Nazis murdered between 250,000 and 500,000 members of the groups over the course of the conflict, killing some in extermination camps and subjecting others to starvation, disease and forced labor.

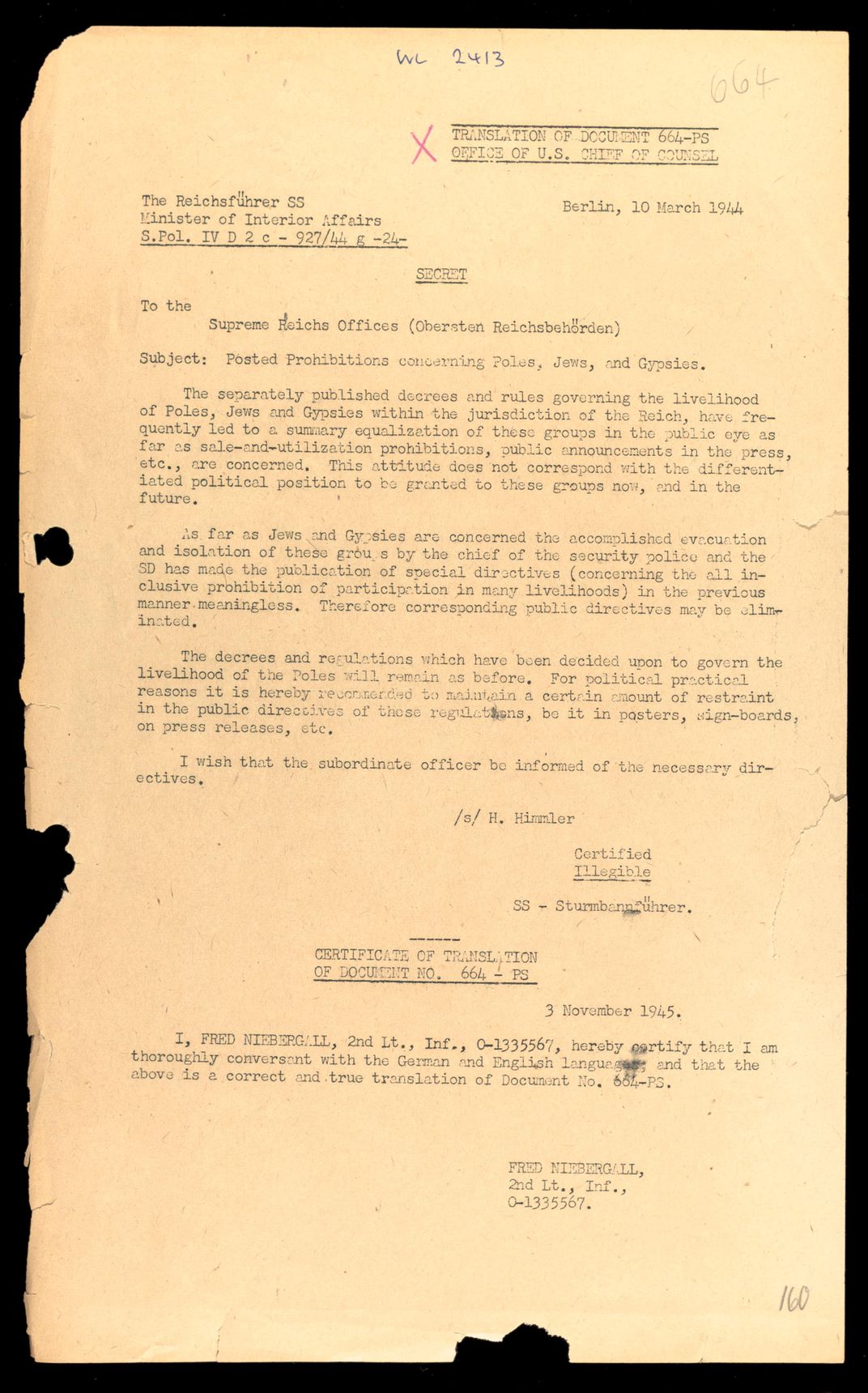

A particularly chilling document on display at the Wiener Library outlines the Nazis’ genocidal policies in plain terms. Signed by Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, the March 1944 note confirms “the accomplished evacuation and isolation” of Jews and “Gypsies.” In other words, Warnock explains to Caroline Davies of the Guardian, “They have been forced out, or killed. The whole of the Reich has been cleansed in this murderous way.”

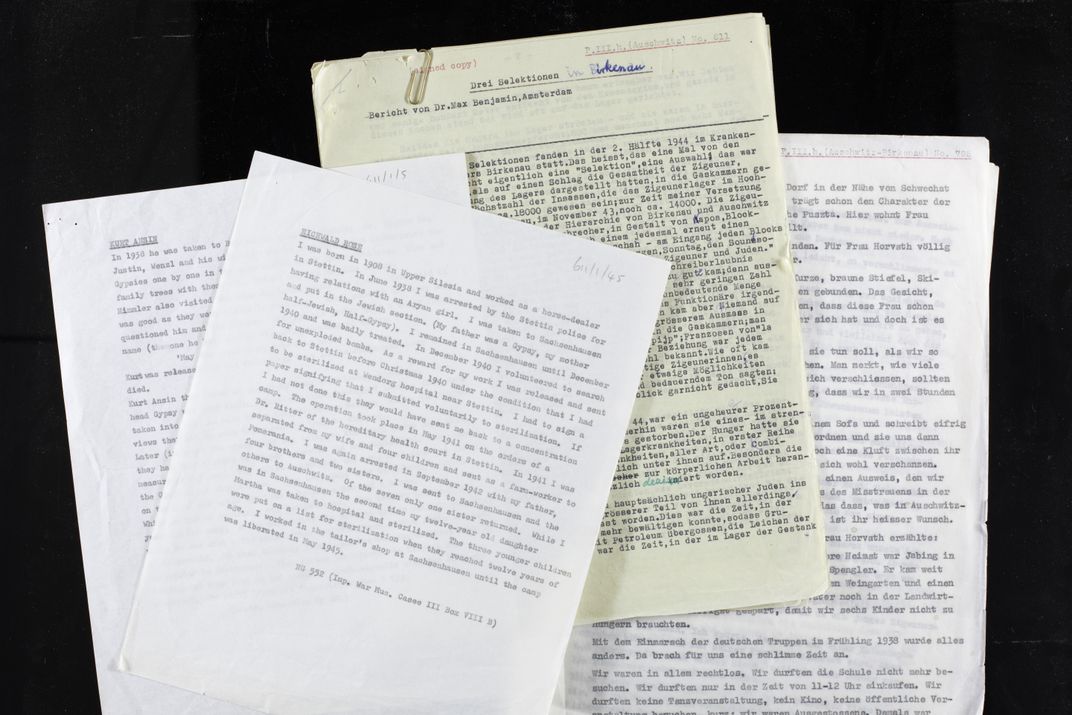

To piece together a narrative of Roma and Sinti Holocaust experience, the Wiener Library turned to its vast collection of firsthand testimonies, many of which were recorded by researchers at the institution during the 1950s. In total, the London library holds more than 1,000 accounts from witnesses to Nazi genocide and persecution, among them Roma and Sinti survivors. An additional collection assembled in 1968 “contains a wealth of material relating to the persecution of Roma and Sinti under the Nazis,” according to a statement.

One individual featured in the exhibition is Margarethe Kraus, a Czech Roma deported to Auschwitz in 1943. Just 13 years old at the time, she underwent maltreatment and forced medical experimentation during her internment. Kraus survived the war; her parents did not.

Hermine Horvath, an Austrian Roma woman deported first to Auschwitz-Birkenau and later to Ravensbrück, was similarly subjected to medical experimentation. Rather remarkably, Horvath also spoke patently about the sexual abuse she suffered at the hands of an SS official.

“Her account is unusual because there was a reluctance to speak about sexual violence, possibly to protect their families, possibly, and unfortunately, because of a sense of shame themselves,” Warnock tells Davies.

Horvath survived the Holocaust but died at age 33 not long after giving her testimony.

The marginalization and persecution of the Roma and Sinti did not end with the war’s conclusion. Crimes against the two groups were not specifically prosecuted during the Nuremberg Trials, and Germany only acknowledged that the Roma and Sinti had been victims of racial policy in 1979; previously, the Federal Republic of Germany insisted that victims were only incarcerated because they were criminals.

This misguided determination had “effectively closed the door to restitution for thousands of Roma victims, who had been incarcerated, forcibly sterilized, and deported out of Germany for no specific crime,” the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum notes. The Wiener Library exhibition explores Roma and Sinti survivors’ efforts to gain recognition for their suffering during the post-war period; still, by the time these individuals were able to seek compensation, many who would have been eligible had died.

Today, the Roma people (often used as a blanket term that encompasses several groups) represent Europe’s largest ethnic minority. But they remain profoundly marginalized, facing impoverishment, vilification by politicians and even violence.

As Ian Hancock, a Romani scholar at the University of Texas at Austin, tells Al Jazeera’s Shackle, lack of knowledge regarding the persecution of Roma and Sinti during WWII is due at least in part to “prejudice against us, and ignorance about our history.”