Library of Congress’ Presidential Papers, From Washington’s Geometry Notes to Wilson’s Love Letters, Are Now Online

Four newly added collections mark the conclusion of a two-decade digitization project

:focal(392x262:393x263)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ab/fc/abfcce6f-8aee-49c0-af17-daa5451f7f9b/pres_papers2.jpg)

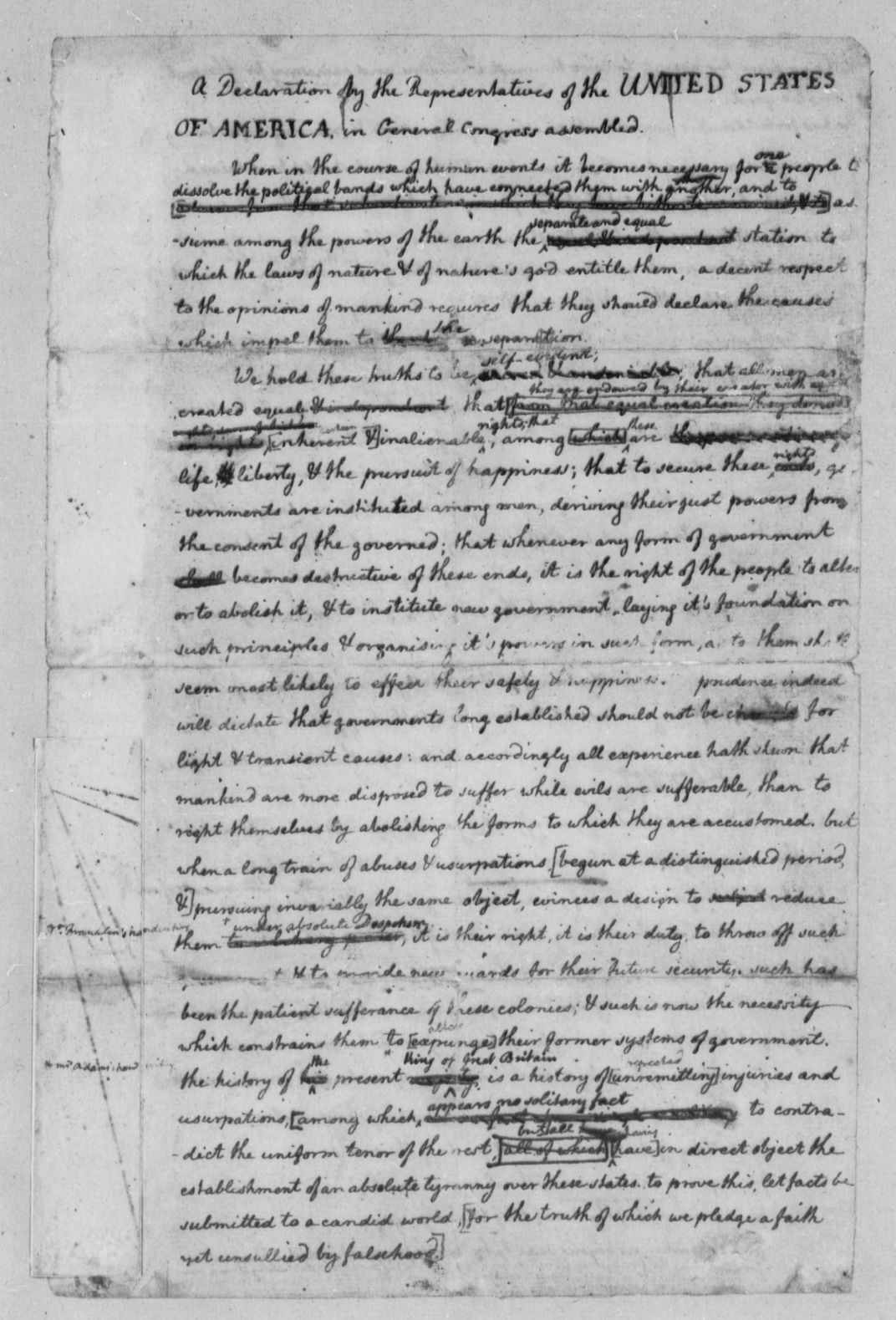

Though it’s not quite the same as being in the room where it happened, poring over Thomas Jefferson’s handwritten rough draft of the Declaration of Independence—complete with edits and scratched-out words—will likely offer any American history buff a thrill.

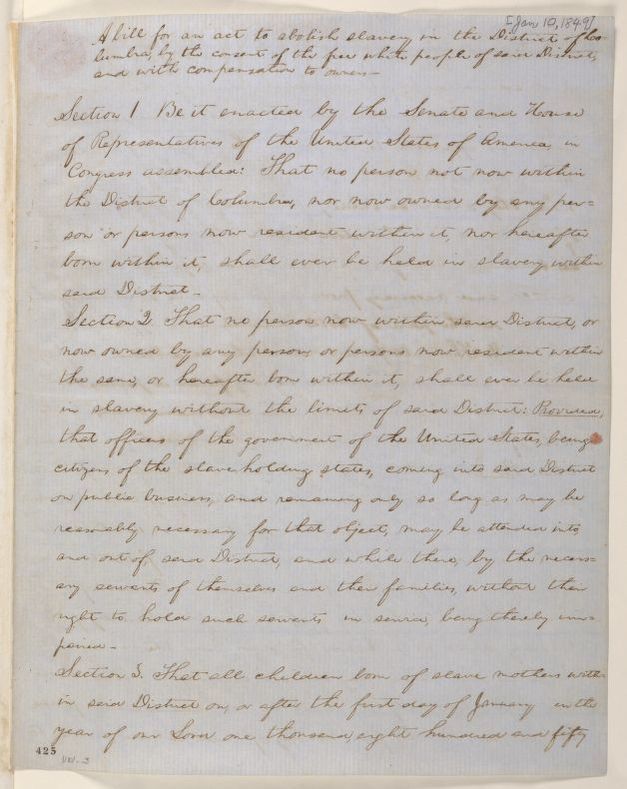

Thanks to the completion of a major digitization project by the Library of Congress (LOC), that 1776 document and millions of others are now available for all to study and explore. As the Washington, D.C. cultural institution announced this week, a two-decade campaign to digitize all of the presidential papers in its collections has drawn to a close with the archives of presidents Grover Cleveland, Benjamin Harrison, William Howard Taft and Calvin Coolidge.

All told, archivists digitized the papers of 23 American presidents, from George Washington to Coolidge. Per a statement, staff uploaded more than 3.3 million images to the online portal. (The National Archives and Records Administration, which is also based in D.C., oversees the presidential libraries of 31st President Herbert Hoover and his successors.)

“Arguably, no other body of material in the Manuscript Division is of greater significance for the study of American history than the presidential collections,” says Janice E. Ruth, chief of the library’s manuscript division, in the statement. “They cover the entire sweep of American history from the nation’s founding through the first decade after World War I, including periods of prosperity and depression, war and peace, unity of purpose and political and civil strife.”

Highlights of the collections include first drafts of George Washington’s and Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural speeches, as well as the first president’s commission as commander in chief of the American army.

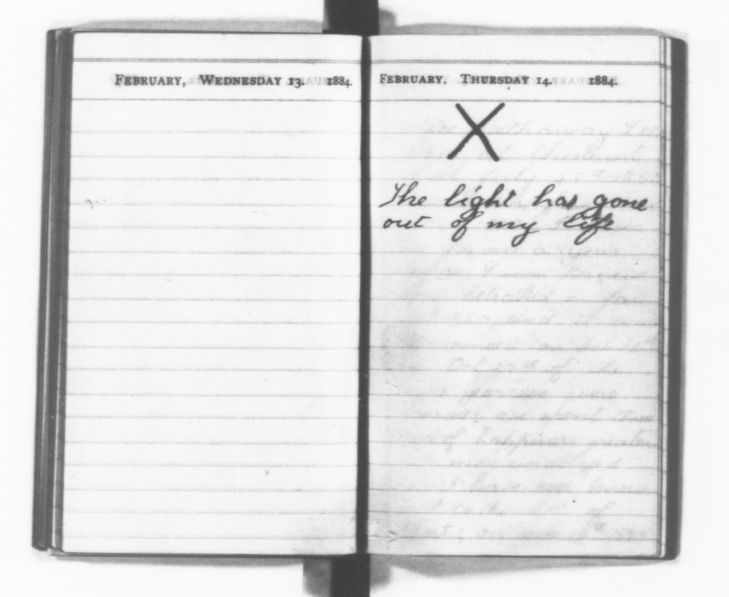

The papers also provide glimpses into these historical figures’ private lives. After Theodore Roosevelt’s wife and mother died on the same day—February 14, 1884—the 26th president penned a diary entry featuring a large black “X” and a poignant phrase: “The light has gone out of my life.”

From Taft’s telegram messages about survivors of the sinking of the Titanic to Woodrow Wilson’s love letters and a 13-year-old Washington’s notes about geometry, virtually every chapter in the presidents’ lives has been meticulously preserved.

The library’s Taft and Coolidge collections represent the largest troves of original documents from these men in the world, constituting 676,000 and 179,000 items, respectively. Other LOC presidential collections said to be the largest of their kind include the papers of Washington, Jefferson, Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson.

“The writings and records of America’s presidents are an invaluable source of information on world events, and many of these collections are the primary sources for books and films that teach us about our nation’s history,” says Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden in the statement. “We are proud to make these presidential papers available free of charge to even more researchers, students and curious visitors online.”

Though the LOC and the National Archives house the majority of presidents’ personal papers, several exceptions exist: The writings of John Adams and John Quincy Adams belong to the Massachusetts Historical Society, for instance, while the Ohio Historical Society houses Warren G. Harding’s papers.

In an email, Charles A. Hyde, president and CEO of the Benjamin Harrison Presidential Site in Indianapolis, Indiana, tells Smithsonian magazine that he hopes the new digitization effort encourages the study of all presidents—especially ones who are sometimes overlooked.

“We applaud the Library of Congress’ efforts to digitize invaluable primary resources, giving an unprecedented glimpse into an American president whose legacy has surprising and renewed relevance to conversations our country is having today,” says Hyde.

He notes that Harrison, who served as the 23rd president between 1889 and 1893, was an “outspoken” advocate for African American civil rights, in addition to signing the Sherman Antitrust Act and promoting conservation of natural resources through the creation of the 1891 Forest Reserve Act.

Hyde adds, “We hope [this new digitization effort] will help engage and inspire new research into one of our country’s most enigmatic and underrated chief executives.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)