Five Rarely Seen Frida Kahlo Artworks United for Dallas Exhibition

The show features lesser-known paintings and drawings, most of which date to the end of the iconic Mexican artist’s life

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e5/76/e576b509-74e4-4ea7-b00f-c395ede83228/frida_kahlo_still_life_1951.jpg)

In the years since her death in 1954, many of Frida Kahlo’s self-portraits have achieved international fame. Displayed in museums around the world, the Mexican artist’s stunning, Surrealist renderings of her own visage have also been reproduced on keychains, T-shirts, coffee mugs and more.

But Kahlo’s famous self-portraits represent only a slice of her artistic practice. Now, thanks to a rare exhibition at the Dallas Museum of Art (DMA), Kahlo enthusiasts can study five of the artist’s lesser-known works in detail.

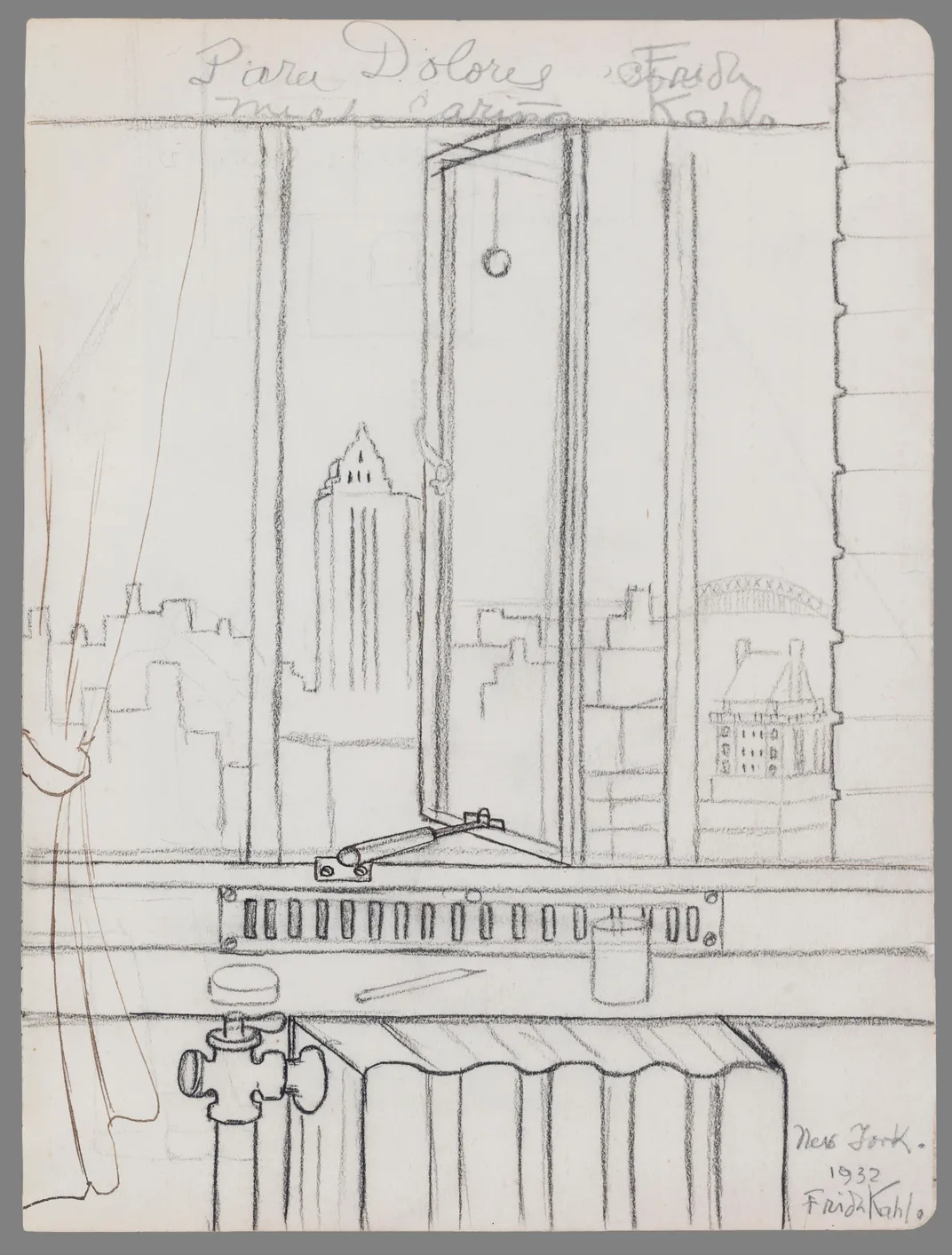

Titled “Frida Kahlo: Five Works,” the show—on view through June 20—unites one drawing from Kahlo’s time in the United States with four works from the latter half of her life. Though small in scale, the exhibition has a wide scope, emphasizing the artist’s skill in still life painting and her enduring interest in Mexican heritage.

“At the heart of the sensational story of Kahlo’s life are captivating works like these,” says Mark A. Castro, who curated the show, in a statement. “[T]hey are visceral in their emotion and vibrant in their execution.”

All of the art featured is on loan from a private collector based in Mexico. Visitors can reserve timed tickets for entry online or explore the show via the museum’s website. (Look out for a virtual tour of the exhibition in the coming months.)

The earliest of the five works, a pencil sketch titled View of New York, dates to 1932. Kahlo, born in Mexico City in 1907, and her husband, Diego Rivera, were living in the United States at the time. Rivera had been commissioned to produce a number of large murals there, similar to the sweeping murals on Mexican and Indigenous history that he’d produced in his home country.

Rivera pops up in another small painting, Diego and Frida 1929—1944 (1944), included in the exhibition. The work stands out because it still resides in its original frame—a curved piece decorated in shells that Kahlo selected herself, per the statement.

Castro tells NPR’s Susan Stamberg that the painting, which fuses Kahlo and Rivera’s faces, might have been a devotional gift for the artist’s husband. On the frame, Kahlo recorded the start of their marriage in 1929 and the date of the work’s creation, marking 15 years in the couple’s turbulent relationship. (The pair famously divorced—and remarried—in 1940.)

As Yvonne S. Marquez reports for Texas Monthly, researchers examined the works with X-ray and infrared photography to glean more insights into Kahlo’s painting style. NPR adds that a team studying Still Life With Parrot and Flag, a 1951 painting featured in the show, found that Kahlo changed the position of a bird’s wing and split open fruit that she had previously painted intact.

Likewise, in the allegorical Sun and Life (1947), conservators discovered that Kahlo opened up the seed pods as she painted, reworking their interiors to add more definition. The work depicts a fetus-shaped seed floating behind a large red sun in a landscape filled with roots and leaves.

“The [seed] behind the sun … was originally shown almost entirely closed,” Castro tells Texas Monthly. “I wonder if there is a connection there to the kind of desire to … make something more visible, rather than keeping it more hidden.”

The work is replete with other ambiguous symbols, too. Claudia Zapata, a curatorial assistant at the Smithsonian American Art Museum who wasn’t involved in the exhibition, tells Texas Monthly that the sun’s third eye might have represented “another form of sight, like wisdom,” to Kahlo.

In Sun and Life, adds Zapata, the artist may have included the bright red sun as a symbol “representative of a larger, deeper spiritual connection to the place and to identity” specific to Mexico. Kahlo came of age in the years after the Mexican Revolution, when a group of intellectuals was invested in embracing Mexico’s Indigenous culture and redefining national identity through that lens.

“I think she’s invoking a certain kind of spiritual connection and identity connection to Mexico,” Zapata says.

When Kahlo was 18 years old, she suffered a traumatic injury to her abdomen and pelvic bone as the result of a bus accident. While bedridden and convalescing, she began painting, partly as a means of coping with the physical and psychological pain that would continue to plague her throughout her adult life. The accident also made Kahlo unable to bear children—a source of grief referenced in complex, varied ways throughout her work. (In Sun and Life, the fetus-shaped seed is germinating and weeping, notes Zapata.)

Still life works, such as the two included here—Still Life With Parrot and Flag and Still Life (1951)—dominated much of Kahlo’s practice in her last years, Castro tells NPR. During the early 1950s, the artist battled a series of illnesses and painful surgeries, as well as the amputation of one of her legs due to gangrene (many of these conditions were the result of lingering health problems caused by her 1925 accident).

In these arrangements, Kahlo populated scenes with brightly colored fruits and items that she employed as symbols of Mexican national heritage and its Indigenous history. The artist told her friends that she painted still life works during this period because they sold better than her explicitly autobiographical works—and “they were easier to do,” per NPR.

Whatever the reason, the works included in the Dallas exhibition mark some of the final images that Kahlo produced. In her last diary entry, written shortly before her death on July 13, 1954, Kahlo mused, “I hope the exit is joyful—and I hope never to return.”

“Frida Kahlo: Five Works” is on view at the Dallas Museum of Art through June 20.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)