Why the Much-Publicized Mission to Find Amelia Earhart’s Plane Is Likely to Come Up Empty

The explorer who discovered the ‘Titanic’ is searching for the lost aviator. A Smithsonian curator doesn’t think he’ll find it.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/12/35/12352172-4d65-462f-bf9c-cda608f773b5/gettyimages-90758090.jpg)

It has been more than 80 years since Amelia Earhart vanished during her ill-fated attempt to circumnavigate the globe—and for more than 80 years, people have been looking for any trace of the famed aviator. Last week, the news was announced that a search expedition will head to the island of Nikumaroro, an uninhabited fleck in the Pacific where, according to one theory, Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, made an emergency landing and eventually died. At the helm of the new venture is Robert Ballard, the oceanographer who found the sunken wreck of the Titanic.

The expedition, which sets off on August 7, will make use of the E/V Nautilus, a research vessel equipped with advanced seafloor-mapping technologies, among other systems. The hope is to find some sign of Earhart’s plane at the bottom of the ocean, reports Rachel Hartigan Shea of National Geographic, which is filming the expedition for a documentary that will air in October. At the same time, an archaeological team will be investigating certain sites on land, looking for any hints that Earhart and Noonan were there.

Ballard is a star of deep-sea exploration; in addition to the remains of the Titanic, he has uncovered the wreck of John F. Kennedy’s WWII patrol boat, the sunken Nazi warship Bismarck and ancient shipwrecks in the Black Sea. Ballard believes that the waters around Nikumaroro could hold the key to one of the most enduring mysteries of the 20th century: What happened to Earhart and Noonan on that fateful day of July 2, 1937?

“I wouldn’t be going if I wasn’t confident,” Ballard tells Bianca Bharti of the National Post. “Failure is not an option in our business.”

But Dorothy Cochrane, a curator at the aeronautics department of the National Air and Space Museum, doubts that the upcoming expedition to Nikumaroro will turn up any tangible signs of Earhart’s plane. It is highly unlikely, she says, that Earhart and Noonan ever ended up on the island.

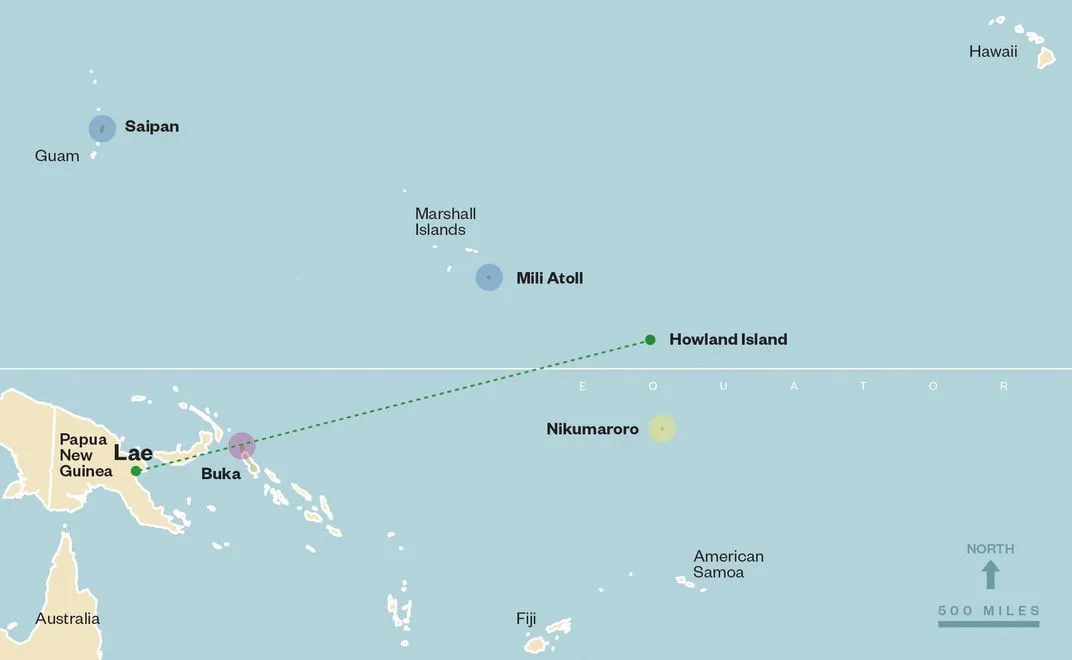

The Nikumaroro theory has been enthusiastically promoted by The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR), a non-profit that has long been on the hunt for Earhart. The gist of the theory is as follows: Unable to locate a designated refuelling station on Howland Island, another uninhabited spot in the central Pacific, Earhart and Noonan made an emergency landing on a reef of Nikumaroro, which sits around 350 nautical miles southeast of Howland. As Alex Horton of the Washington Post explains, Nikumaroro is a plateau that rises above sea level with a 10,000-foot slope plummeting down to the ocean floor. Ballard and his colleagues will be basing their search on the belief that Earhart’s Lockheed Electra plane eventually washed down the slope, leaving Earhart and Noonan stranded on the island.

But this theory, according to Cochrane, “doesn’t follow the facts of [Earhart’s] flight.” Hours before her disappearance, the aviator had taken off from Lae, New Guinea, with the intention of making a crucial stop on Howland, where the Coast Guard cutter Itasca was waiting to help guide her to the island. “They had a place for her to stay overnight,” Cochrane explains. “They had fuel for her to move on to her next long, over-water flight.”

As early morning broke on July 2, Coast Guard radio personnel began picking up Earhart’s calls—and Cochrane says that with each call, the intensity of her radio signal was increasing, suggesting that she was getting ever closer to Howland Island. It soon became clear that the flight was going perilously wrong—“We must be on you, but we cannot see you. Fuel is running low,” Earhart radioed at 7:42 a.m.—but both Earhart and the Coast Guard seemed to believe that her plane was near Howland.

“The personnel on the ship are running around looking for her,” Cochrane says. “Her radio strength is close by ...They all think that she's close by, possibly within view.”

At 8:45 a.m., Earhart reported that she and Noonan were “running north and south”—and then, silence. Before the Coast Guard lost contact with her, Earhart had not mentioned that she was going to try and land elsewhere. “And if she's so worried, she's so low on fuel, how is she going to fly another 350 or 400 miles to another island?” Cochrane asks. She concurs with the U.S. government’s conclusion as to Earhart’s fate: she and Noonan ran out of fuel and crashed into the Pacific Ocean.

“She was close to [Howland] island,” Cochrane maintains. “There's just no question about it.”

Proponents of the Nikumaroro theory have put forth several pieces of purported evidence to support their ideas about how Earhart met her unfortunate end. Among them is a blurry photo taken off the coast of the island in 1937; TIGHAR contends that the image may show a chunk of the Lockheed Electra’s landing gear sticking up from the waters’ edge. Last year, a forensic re-assessment of bones found on Nikumaroro in 1940 concluded that they could have belonged to Earhart—though doctors who initially examined the remains believed that they came from either a European or Polynesian male. The bones themselves have disappeared, so the new analysis was based on decades-old measurements.

Also last year, TIGHAR presented a study that found that dozens of previously dismissed radio calls were in fact “credible” transmissions from Earhart, sent after her plane went missing. The results of the study suggest that the aircraft was on land and on its wheels for several days following the disappearance," Ric Gillespie, executive director of TIGHAR, told Rossella Lorenzi of Discovery News at the time.

But Cochrane is not convinced by any of these details. For one, the Coast Guard and the Navy conducted an extensive search for Earhart in the wake of her disappearance and did not find any trace of her near Howland Island or beyond it. “They over-flew [Nikumaroro] island within a week, and they saw nothing,” Cochrane explains. “It's just inconceivable that they would not have seen her if she was on [Nikumaroro] in some fashion.” And as for TIGHAR’s assessment of the supposed post-disappearance radio transmissions, Cochrane says that “[m]any people claimed to hear her voice or distress calls but none of these were ever confirmed or authenticated.”

Cochrane knows that people will continue to look for Earhart until something, anything connected to her is discovered—and in fact, Cochrane thinks it is entirely possible that the aviator’s plane will one day be found in the vicinity of Howland Island. But she also hopes that as we furrow our brows over the mystery of Earhart's disappearance, we take time to appreciate the impressive feats she accomplished while still alive: soaring to the heights of a male-dominated industry, writing, delivering lectures and advocating for equal rights and opportunities.

“[S]he worked in her own career,” Cochrane says. “She's got a very strong legacy of her own.”

Editor’s Note, July 31, 2019: A previous version of this article incorrectly quoted Cochrane saying “They over-flew Howland island within a week, and they saw nothing,” when, in fact it should read: “They over-flew [Nikumaroro] island within a week, and they saw nothing." The story has been edited to correct that fact.