New Book Details the Lives of Vincent van Gogh’s Sisters Through Their Letters

The missives reveal that the Impressionist artist’s family paid for his younger sibling’s medical care by selling 17 of his paintings

:focal(392x308:393x309)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c0/29/c029e07f-8362-4419-a33e-793cc1dc3a9f/van_gogh_sisters3.jpg)

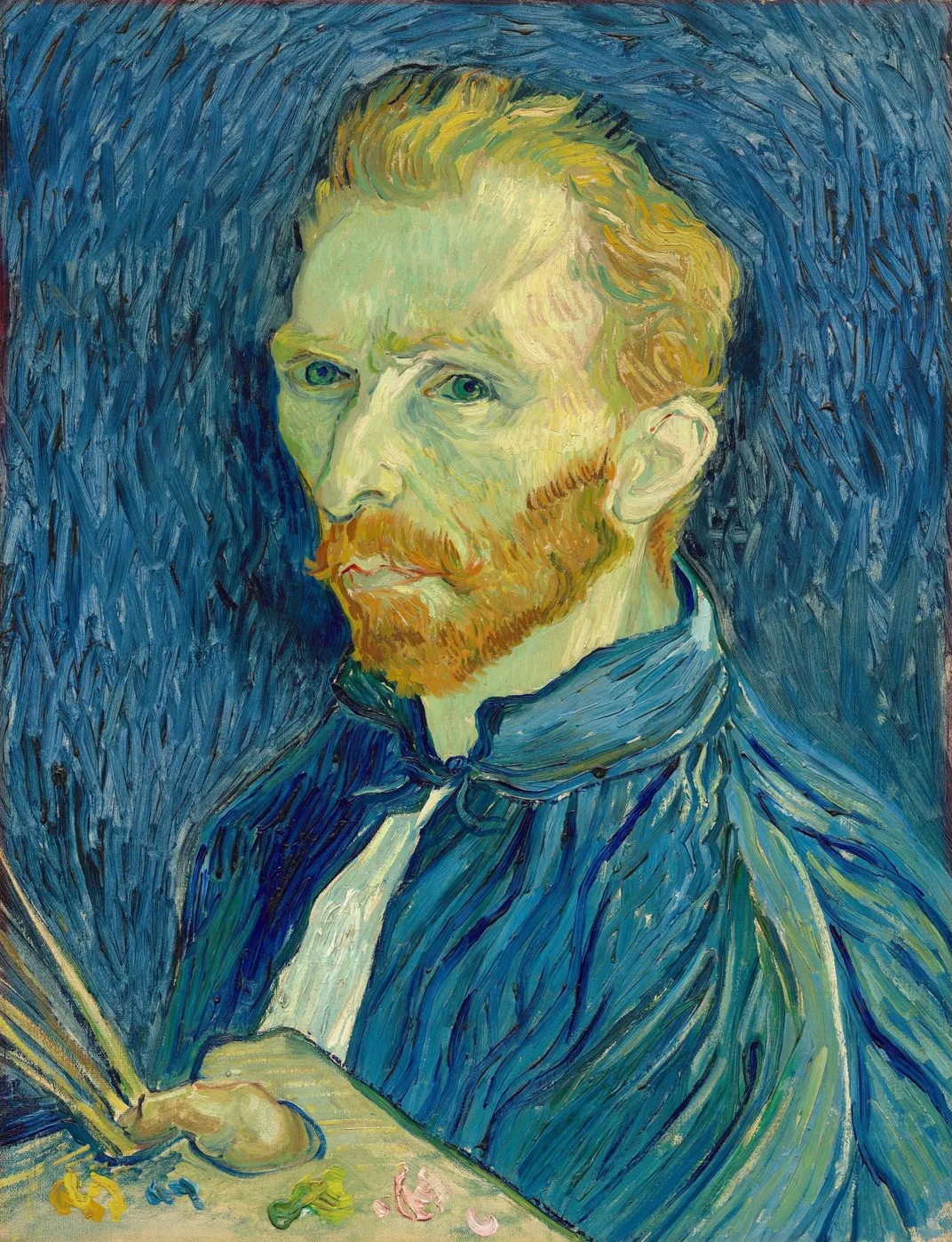

Much ink has been spilled about Vincent van Gogh’s relationship with his younger brother Theo, an art dealer who steadfastly supported the painter’s career even as his mental health deteriorated toward the end of his life.

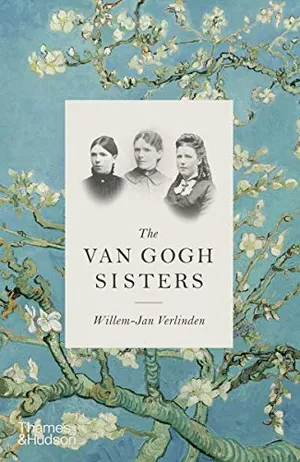

Comparatively, far less has been said about the lives of the artist’s three sisters: Anna, the eldest; Elisabeth, or Lies; and Willemien, the youngest, who was better known as Wil. Now, reports Dalya Alberge for the Guardian, a new book by Dutch art historian Willem-Jan Verlinden seeks to help rectify this imbalance.

Aptly titled The Van Gogh Sisters, the upcoming release draws on hundreds of previously unpublished letters written by the three women, many of which are printed in English for the first time. (A Dutch version of the book was initially published in 2016.)

As Verlinden writes on his website, the work “provides an impression of the changing role of women in the 19th and early 20th century, of modernization, industrialization, education, feminism and the fin de siècle, of 19th-century art and literature, and—of course—of Vincent’s death and his meteoric rise to fame.”

The Van Gogh Sisters

This biography of Vincent van Gogh’s sisters tells the fascinating story of the lives of three women whose history has largely been neglected.

Previously, the letters were only available in Dutch through the archives of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. They represent “a real goldmine,” as senior researcher Hans Luijten tells the Guardian. “They’re so interesting. One by one, we intend to publish them in the near future.”

The missives also contain some surprising revelations. Most notably, the correspondence shows that the van Gogh family was able pay for Wil’s medical care by selling 17 of her brother’s paintings after his death in 1890.

Wil, born in 1862, traveled widely as a young adult, alternatively seeking employment as a nurse, governess and teacher. Per Velinden’s website, she was active in turn-of-the-century Paris’ early feminist wave and accompanied her brother Theo on visits to Edgar Degas’ studio.

As the Van Gogh Museum notes, Wil and Vincent were particularly close. They bonded over their shared love of art, and she was the only sibling who regularly corresponded with him throughout the final year of his life, when he was living in a mental hospital.

Both van Gogh siblings experienced intense mental illnesses that worsened with age. Near the end of his short life, Vincent struggled with panic attacks and hallucinations, which once famously led him to cut off his own ear. Some modern researchers have gone so far to suggest that the artist’s anxiety, depression and other illnesses were partially caused by genetics and may have run in the family.

Wil never married. She lived with her mother, Anna Carbentus van Gogh, until the latter’s death in 1888, and was herself institutionalized in 1902. The youngest van Gogh sister spent the remaining four decades of her life in a psychiatric facility, where she was fed artificially and “barely spoke for decades,” according to the museum. She died in 1941 at the age of 79.

The official diagnosis for Wil’s illness was Dementia praecox, a 19th-century catch-all term used to describe deteriorating “madness.” Today, Verlinden tells the Guardian, this condition would likely warrant medication or a more humane form of medical care.

“At that time, it meant that you had to be sent to an asylum,” the scholar says. “She stayed there half her life. That’s the sad thing.”

He adds, “But the beautiful thing is she had 17 paintings that Vincent made for her and her mother and the sale was used to pay for her.”

The fact that Vincent’s paintings commanded relatively high prices so soon after his death is a “startling revelation,” as the painter himself had died penniless, writes Caroline Goldstein for Artnet News.

A 1909 letter from Anna to Jo Bonger, Theo’s wife, details the sale of one such painting: “I remember when Wil got the painting from Vincent, but what a figure! Who would have thought that Vincent would contribute to Wil’s upkeep in this way?”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d6/57/d6577f9a-d470-4183-89d2-5b6a99783825/van_gogh_sister.jpeg)

Anna went on to note that Wil refused to go on walks with nurses at the asylum. Instead, she spent most of her days sitting, sewing or reading the epic poem Aurora Leigh, reports the Guardian.

Though Vincent would ultimately become famous for his depictions of Sunflowers and such undulating landscapes as Starry Night, he also memorialized his family members in paint. In one November 1888 missive to Wil, the artist included a small sketch of a recently finished painting, Memory of the Garden at Etten, which was based on memories of his parent’s home in Holland.

The brightly colored composition depicts two women, one old and one young, walking along a path.

“[L]et us suppose that the two ladies out for a walk are you and our mother … the deliberate choice of colour, the somber violet with the blotch of violent citron yellow of the dahlias, suggests Mother’s personality to me,” Vincent muses.

He goes on to describe the colors of the painting in detail, explaining how the sandy path is composed of a “raw orange” and describing the various contrasts between the blue fabric and the white, pink and yellow flowers that populate the scene.

Vincent adds, “I don’t know whether you can understand that one may make a poem only by arranging colours, in the same way that you can say comforting things in music.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d9/1d/d91d1676-aab5-440e-b1f7-9d19bb14a5cc/novel_reader.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)