Exploring Paul Revere’s Legacy Beyond His Famed Midnight Ride

Before becoming an American legend, the Revolutionary War hero was best known as a skilled artisan, activist and entrepreneur

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b4/ec/b4ec743d-e80a-4b95-b4ef-71e3647d9bb8/merlin_159947583_8a3a18ed-ff19-4050-93f8-4d5aa81dcf3e-jumbo.jpg)

A bronze bell, an engraving of the Boston Massacre and a pair of silver wine goblets are among the more than 140 artifacts featured in the New-York Historical Society’s latest exhibition. Titled Beyond Midnight: Paul Revere, the show strives to showcase its subject’s lesser-known accomplishments—from his career as an enterprising artisan to his involvement in the underground Sons of Liberty group—and dispel myths surrounding the Revolutionary War hero’s famed midnight ride.

“The ride is one day of his life, one very long day in one very long life,” curator Lauren B. Hewes tells the New York Times’ James Barron. “If you can only be known for one day, that’s not a bad day to be known for, but he did all these other things.”

The future revolutionary was born in Boston in December 1734. The son of a French Huguenot immigrant, he took over the family shop at age 19, quickly rising to prominence as a skilled master craftsman. In addition to creating such items as silver tea sets, butter boats and spoons, Revere demonstrated his entrepreneurial bent by branching out into copperplate engraving and even dentistry. During the 1760s and '70s, he became an increasingly ardent activist, acting as a courier for patriot groups and helping to plan the 1773 Boston Tea Party.

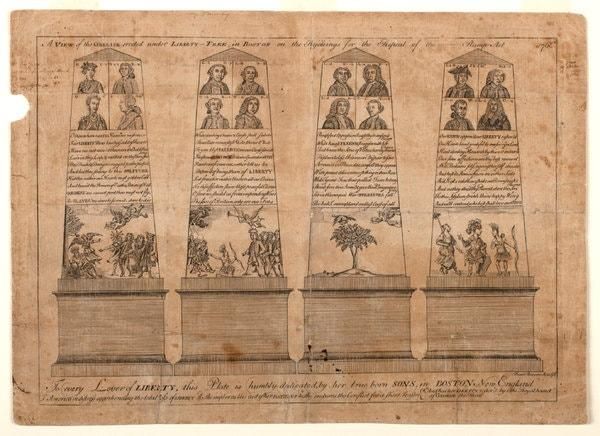

Per a press release, Beyond Midnight opens with a 9-foot-tall replica of an obelisk erected in Boston following the repeal of the Stamp Act in 1766. The celebratory structure was destroyed soon after its creation, but its likeness lives on in an engraving created by Revere and now highlighted in the show. Additional examples of the craftsman’s artistic prowess include a 1770 engraving of British forces’ landing at Boston’s Long Wharf and four versions of an engraving depicting the Boston Massacre.

As Barron reports for the Times, Revere’s rendering of the 1770 massacre was essentially a slightly tweaked copy of an earlier version by engraver Henry Pelham. Since Revere printed the engraving faster than his competitor, he received the credit and saw his work circulated across both Boston and the wider European market. To modern audiences, this tactic may sound like unabashed plagiarism, but as Hewes explains, the politically savvy patriot’s main goal was spreading propaganda as quickly as possible. He “was not unlike a partisan blogger,” the curator says. “He understands propaganda, positioning yourself, telling the story in the way you think it should be told.”

Embellished narrative plays a key role in Revere’s larger legacy. Poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow immortalized “the midnight ride of Paul Revere, / On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-Five,” but the much-mythologized event unfolded very differently in real life. As Kat Eschner wrote for Smithsonian.com in 2017, Revere was one of three men tasked with warning locals of British troops’ impending arrival: “A more accurate title [for Longfellow’s poem] would have been ‘The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere, William Dawes and Samuel Prescott.”

Other romanticized aspects of the story include the silversmith’s harrowing horse ride—he made the first part of the journey on foot, then rode a borrowed horse the rest of the way—and his success as a master of espionage. Of the three men who raised the call, only Prescott made it to his final destination; Revere was captured by British officers, while Dawes escaped the soldiers but lost his horse and had to turn back.

Longfellow’s heavily fictionalized account “was not intended as a detailed examination of the ride,” exhibition organizer Debra Schmidt Bach tells the Times. Instead, Bach says, the poem strove to stoke revolutionary fervor and patriotism (the work was published just ahead of the Civil War) by presenting Revere as the ultimate American hero.

After the Revolutionary War ended, the midnight messenger returned to the craft business, leaving his oldest son to run the family silver shop while he launched a new hardware store. Later, Revere opened a foundry popular for producing cannons and metal bells. His obituary, published following his death at age 83 in May 1818, stated, “Seldom has the tomb closed upon a life so honorable and useful.”

Beyond Midnight: Paul Revere is on view at the New-York Historical Society through January 12, 2020.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)