“Explosive” Eruptions Possible at Hawaii’s Kilauea Volcano

Steam-powered bursts could fling multi-ton boulders half a mile away, but the USGS says wide-scale destruction is not likely

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/00/99/0099c951-8ccb-4e95-bec3-431069ace83b/summit_lava.jpg)

Last week, the Kilauea volcano on the island of Hawaii began oozing lava from 15 cracks in its East Rift Zone, destroying streets and burning up three dozen homes in the Leilani Estates subdivision. Officials are also warning residents of toxic sulfur dioxide emissions.

Now, the USGS Hawaii Volcano Observatory is warning that the crater at the summit of Kilauea has been undergoing changes and could begin spewing ash, gas and rocks weighing several tons over the next few weeks.

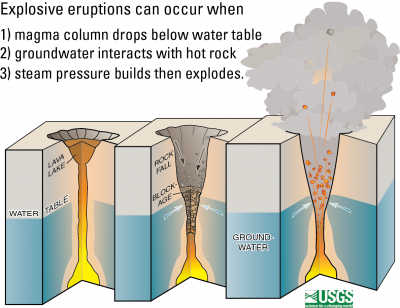

As fissures opened up on Kilauea's slopes, geologists also watched as levels of the Halema‘uma‘u lava lake at the volcano's summit dropped almost 1,000 feet. As Maddie Stone at Earther reports, the summit crater is fed by a larger chamber of magma beneath the volcano via a narrow passageway. As that magma flows from the chamber and out of the fissures on the volcano's flanks, the lava level in the center crater falls. But this has caused rock and debris from the crater's edges to fall into the hole, which has sparked columns of ash to rise from the crater.

And the further the lava level drops, the more precarious the situation becomes. If the lava drops below the water table, the encroaching water would turn to steam, building up pressure beneath the plug of fallen rocks and debris. Eventually, this may lead to an explosion that could shoot rocks as large as several tons up to half a mile away, pebbles several miles away and plume of ash up to 20 miles away.

Though volcanologists can no longer get close enough to the crater to gather readings, they are using airborne thermal imaging to peer inside. As of this morning, the USGS says the lava lake level continues to drop and seismic activity is high. Rockfalls into the crater are generating small ash clouds, but active eruption and spatter has paused along the lower flanks overnight—yet could still restart at any time.

The Volcano Observatory says they cannot predict with certainty if or when these steam driven explosions will occur or how large they might be. But so far, the sequence of events seems similar to explosive eruptions that took place at the volcano in 1924. In February of that year, the lava in Halema‘uma‘u began draining out of the crater. In April, swarms of earthquakes began in the area, and in May the crater began erupting, ejecting gas, ash and boulders up to 14 tons during 50 eruptions over the course of two and a half weeks.

The USGS reports that similar explosions are likely to happen again, especially after magma migrates into the rift zones on the volcano's flanks, which seems to be occurring now.

However, even if Kilauea does begin an explosive eruption, geologists say it will not be an event like Mount Saint Helens or other major eruptions. Those types of big blowouts usually take place in stratovolcanoes, steep-sided, cone-shaped volcanoes where pressure builds up in a central vent until the mountain pops in a dramatic explosion.

Kilauea, however, is a shield volcano, where basaltic lava flows almost continuously out of a summit crater and other vents, building a flat dome. Shield volcanoes rarely build up enough pressure to have catastrophic explosions though sometimes steam explosions like the ones predicted are possible.

“If an explosion happens, there’s a risk at all scales. If you’re near the crater, within half a mile, you could be subject to ballistic blocks weighing as much as 10 or 12 tons,” Donald Swanson of the Obervatory tells The Washington Post. But he also tells Reuters that there’s not too much cause for alarm for most people. “We don’t anticipate there being any wholesale devastation or evacuations necessary anywhere in the state of Hawaii.”

Nearly 2,000 residents evacuated due to the lava flows. Dozens of these people from Leilani Estates, where the USGS warns more fissures may open, still remain in shelters.