‘Exquisitely Preserved’ Skin Impressions Found in Dinosaur Footprints

The fossils were so well-preserved that the researchers could even see marks left by raindrops

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9f/c0/9fc021c1-74db-4b68-83c1-38b8a027be84/screen_shot_2019-04-11_at_111339_am.png)

During a large-scale excavation at the Jinju Formation in South Korea, a set of five tiny dinosaur tracks were spotted on a slab of fine, grey sandstone. This in itself wasn’t unusual; paleontologists find dinosaur footprints relatively often. But when Kyung-Soo Kim of South Korea’s Chinju National University of Education and his colleagues took a closer look at the tracks, they could see impressions of the prehistoric creature’s skin—a rarity, since less than one percent of dinosaur print show skin traces. And that wasn’t all.

“These are the first tracks ever found where perfect skin impressions cover the entire surface of every track,” says Martin Lockley, a geologist at the University of Colorado Denver and co-author of a new study in Scientific Reports.

The footprints were left by Minisauripus, the smallest-known theropod, meaning it walked on two legs, and an ichnogenus, meaning that it is known only from fossilized footprints and trackways—not from fossilized bone. The tracks are about an inch long and were imprinted during the Early Cretaceous, between 112 and 120 million years ago, making them the oldest Minisauripus footprints in the fossil record, according to Gizmodo’s George Dvorsky.

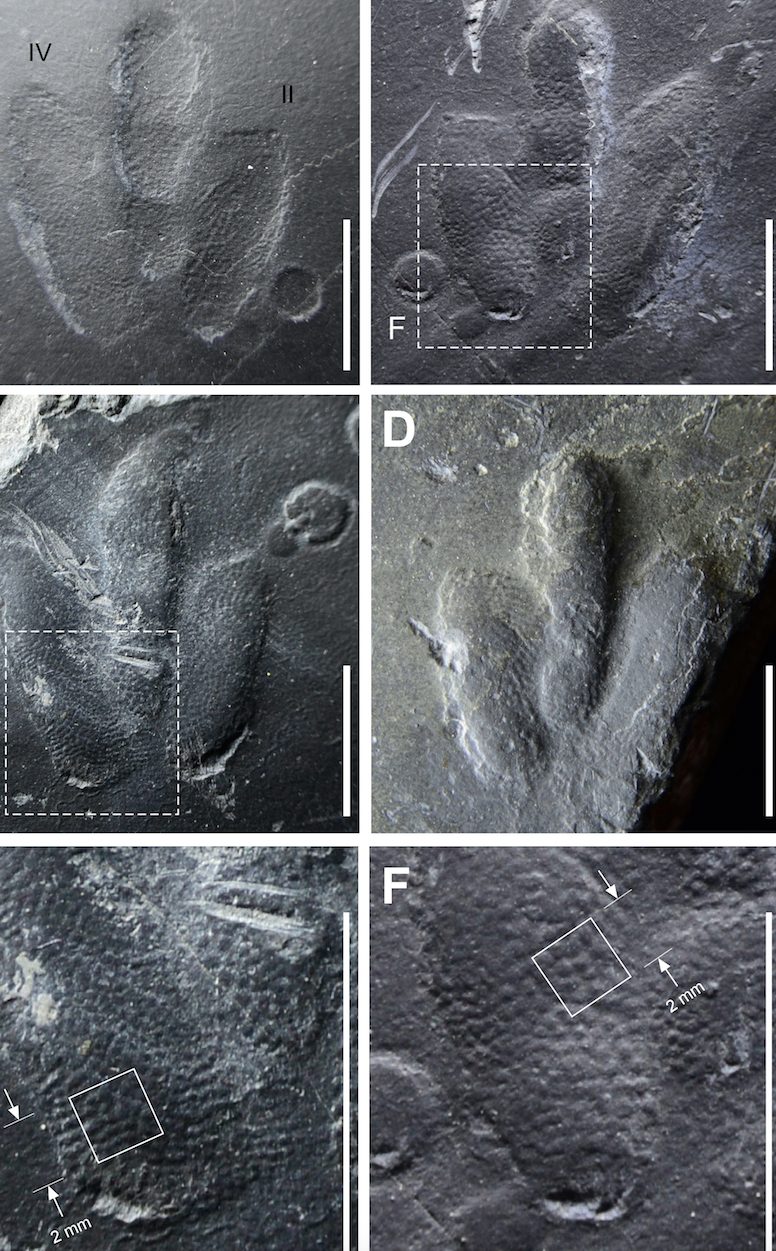

Including the latest discovery, Minisauripus tracks have been found at ten different sites, but this was the first one that still contained traces of the dinosaur’s skin. The imprints are, according to the study authors, “exquisitely preserved.” Experts could see traces of little scales, each between one-third to one-half a millimeter in diameter, displayed in “perfect arrays, like well-woven fabric,” according to the University of Colorado. It is believed that the texture of the dinosaur’s skin was “the grade of a medium sandpaper.”

Skin impressions have been found in dinosaur footprints before, but these impressions were patchy and didn’t cover every print in the trackway. The newly discovered Minisauripus tracks are outliers thanks to “unusual and optimal preservation conditions,” the study authors write. The blackbird-sized dinosaur that made them stepped onto a thin layer of mud, about a millimeter thick, that was sufficiently firm and sticky to stop the animal from sliding around and smudging the prints. It is also possible that the dinosaur had loose and flexible skin, “allowing it to spread when contacting with the substrate so as not to shift or slide and smear the fine skin traces as they were registered,” according to the researchers.

Once the dinosaur had moved on, the tracks were covered with another fine mud layer. Even imprints of raindrops that fell before the dinosaur arrived were preserved on the slab, and the researchers could see that the Minisauripus had stepped on one of drops.

The skin pattern found in the prints is similar to that of Cretaceous-era feathered birds from China, but the shape of the animals’ feet is markedly different, leading scientists to conclude that the tracks were not left by an avian species. Indeed, the Minisauripus skin pattern also bears similarity to fragmentary imprints from larger, carnivorous theropods.

In addition to offering researchers the “first detailed insight into the skin texture of a diminutive theropod,” as the study authors put it, the recent discovery sheds new light on the timeline of the Minisauripus ichnogenus’ presence in modern-day Korea. All previously known Korean Minisauripus tracks were unearthed at a geological site called the Haman Formation, which is between 112 and 100 million years old. The newly found prints, unearthed at the Jinju Formation, are between 10 and 20 million years older, suggesting that the species that left the tracks was frolicking about—and leaving its mark—earlier than previously thought.