Painting Deemed Fake, Consigned to Storage May Be Genuine Rembrandt

New analysis confirms the famed Dutch painter’s studio—and perhaps even the artist himself—created “Head of a Bearded Man”

:focal(1816x1816:1817x1817)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1a/01/1a012e44-78db-4ba7-8fe3-28bed72e4602/bearded_man.jpeg)

Since the 1980s, a postcard-sized painting has sat out of sight in the storeroom of the University of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum. Titled Head of a Bearded Man, the portrait was donated to the museum in 1951 and displayed as an original work by revered Dutch master Rembrandt. But after a group of investigators deemed the painting inauthentic in 1981, curators decided to move it into storage.

“[N]o one wanted to talk about [it] because it was this fake Rembrandt,” curator An Van Camp tells the Guardian’s Mark Brown.

Now, Bearded Man is set to return to public view under decidedly more auspicious circumstances: As the museum announced in a statement, new research has all but confirmed that the painting was created in Rembrandt’s workshop—and perhaps even by the Old Master himself. (Bearded Man will go on display later this week as part of the museum’s “Young Rembrandt” exhibition, which surveys the artist’s first decade of work.)

Van Camp says she had long suspected that the painting might be authentic. When the Ashmolean began to prepare for “Young Rembrandt,” curators and conservators brought Bearded Man to Peter Klein, a dendrochronologist who specializes in dating wooden objects by examining the growth rings of trees.

Klein found that the wood panel on which the work is painted came from an oak tree felled in the Baltic region between 1618 and 1628. According to Martin Bailey of the Art Newspaper, that same exact wood was used in two other works: Rembrandt’s Andromeda Chained to the Rocks (circa 1630) and Rembrandt collaborator Jan Lievens’ Portrait of Rembrandt’s Mother (circa 1630).

“Allowing a minimum of two years for the seasoning of the wood, we can firmly date the portrait to 1620-30,” says Klein in the statement.

Taken together, the evidence constitutes a compelling argument for Bearded Man’s attribution to Rembrandt’s studio. But researchers will need to conduct further study to assess whether the artist personally crafted the work.

As Brigit Katz explained for Smithsonian magazine earlier this year, Rembrandt—like many artists at the time—filled his studio with pupils who studied and copied his distinctive style. Many went on to become successful artists in their own right.

Rembrandt’s wide-ranging influence makes discerning his “true” works a thorny historical task. Since it was founded in the late 1960s, the Rembrandt Research Project has attempted to determine the authenticity of many would-be Rembrandts, offering up designations with multi-million dollar consequences for collectors.

In February, the Allentown Art Museum in Pennsylvania announced its identification of Portrait of a Young Woman as a genuine Rembrandt. The Rembrandt Research Project had rejected the 1632 painting as an original in 1979, calling the work’s authorship into question and downgrading its status to a painting by the artist’s studio. A team of conservators used a variety of high-tech methods to determine that the work was indeed an original.

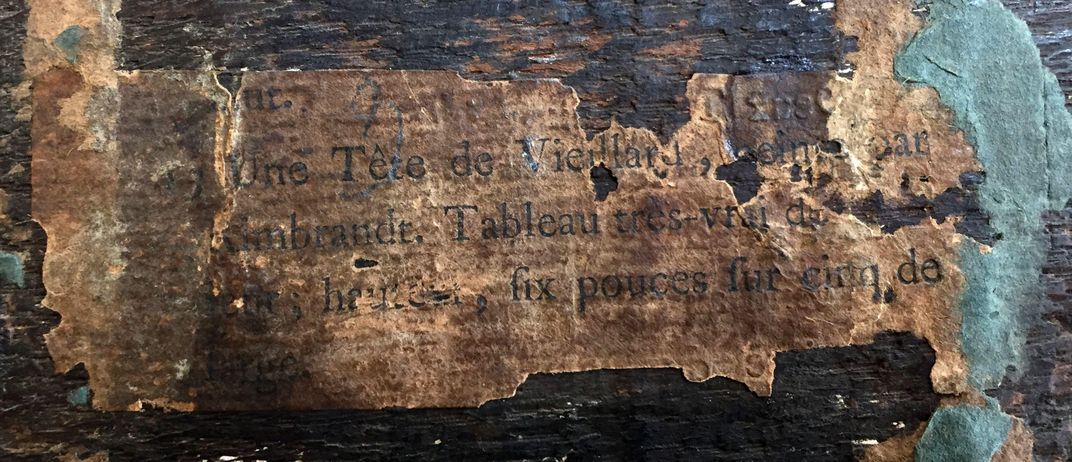

Art dealer Percy Moore Turner bequeathed Bearded Man to the Ashmolean in 1951. A small auction label dated to 1777 and attached to its back identified the work as a Rembrandt painting, but in 1981, the Rembrandt Research Project determined that the work was completed by an artist “outside Rembrandt’s circle” at some point in the 17th century.

Bearded Man depicts an elderly, balding man gazing downward in “melancholy contemplation,” according to Klein.

“Despite overpainting and layers of discolored varnish, expressive brushstrokes show through and convey the troubled face,” says the dendrochronologist. “Head studies such as this are typical of Rembrandt’s work in Leiden and were eagerly collected by contemporaries.”

As Ashmolean conservator Jevon Thistlewood notes in the statement, small parts of the canvas were painted over by an “unknown hand.” These additions “have considerably disrupted the subtle illusion of depth and movement.”

After “Young Rembrandt” closes in November, the team plans to conduct a thorough cleaning and restoration of the work.

Thistlewood adds, “[W]e can’t wait to see what we find.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/37/4c/374cf51c-0a4a-4460-b728-13a854b76d2d/infrared_comparison.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)