Ornately Decorated Eggs Have Been Traded Worldwide for Thousands of Years

A new analysis of ancient ostrich eggs at the British Museum underscores the interconnectedness of the ancient world

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9e/c9/9ec9a9c1-8471-4939-87b7-9924fba85157/eggs.jpg)

For many, this year’s Easter celebrations will be a muted affair. But thanks to new research from the British Museum, April can still be chock full of extravagant eggy fun.

Experts at the London-based institution have reexamined a cache of ornate ostrich eggshells—including five remarkably intact specimens originally found in Italy—in its collections to determine their origins. As the team writes this week in the journal Antiquity, the places where many of the thousands-year-old eggs were found by archaeologists don’t match up with where they were laid, even if ostriches were available to the creators locally. The findings, the researchers argue, highlight the surprisingly complex nature of ancient trade.

Back in the Bronze and Iron Ages, decorated ostrich eggs were among the most valued luxuries. Evidence of their broad societal sway has been found as far back as 5,000 years ago, including in several parts of the world unlikely to have sourced them directly, reports Esther Addley for the Guardian.

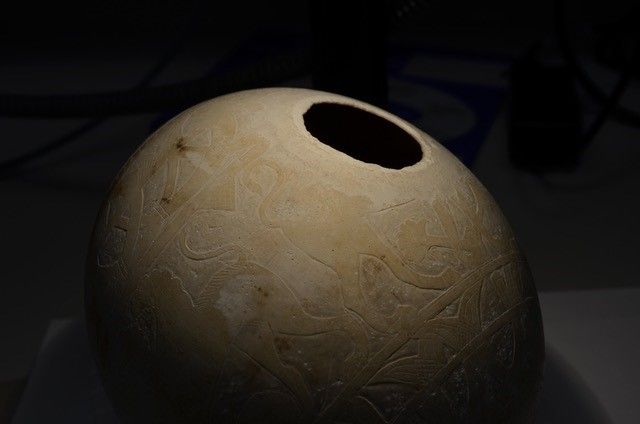

Such was the case for the British Museum’s quintet of pristinely preserved eggs, which were uncovered during the 19th century at the Isis Tomb, a burial site found teeming with elite and expensive goods. Nestled alongside the tomb’s trove of jewelry and trinkets were five painted eggs, four of which were also engraved with geometric patterns and motifs featuring animals, flowers, chariots and soldiers. Though these eggshells and others had previously been studied due to the intricacy of their ornamentations, the details of their creation—and the eggs’ parentage—remained mysterious.

To find the true roots of the eggshells in the museum’s collections, a team led by Tamar Hodos, a researcher at the University of Bristol, studied them with advanced microscopy techniques. Then, the researchers compared the casings’ chemical composition with modern shells from across the Mediterranean and Middle East.

The results suggest that many of the eggs were taken directly from wild ostriches—a “risky undertaking” given how aggressive and dangerous these leggy, fast-moving birds can be, Hodos tells BBC News. “Not only did someone have to find the nest sites, but then they had to steal the eggs.”

The eggs were then ferried to Assyrian and Phoenician artists who meticulously crafted the decorations using a plethora of intricate techniques, the microscopy analysis revealed. After the orbs received their finishing touches, they were sent out into the world, likely via extensive and far-flung trading routes.

Extravagant eggs were so widely and commonly swapped across borders that specimens from different regions often ended up in the same tombs, reports Michael Price for Science magazine. Even eggs excavated from the eastern Mediterranean and northern Africa, where ostriches romped at the time, weren’t always local.

“This was a really unexpected discovery,” Hodos tells the Guardian. “… [J]ust because you could source an ostrich egg locally doesn’t mean you necessarily did.”

Amassing foreign eggs, then, may have been a standard flex for ancient cultural connoisseurs eager to boast of their wealth and means.

The study also highlights the interconnectedness of an ancient world in which residents—not unlike modern ones—were clearly willing to pony up for a flashy, fancy egg. To make that happen, Bronze and Iron Age humans would have needed sophistication, savvy, and the means to move extensively and safely throughout the known world.

As Hodos says in a statement, “The entire system of decorated ostrich egg production was much more complicated than we had imagined.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)