The First Thanksgiving Parades Were Riots

The Fantastics parades were occasions of sometimes-violent revelry

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/05/de/05de78d5-1e10-4e4d-97e2-03b0f9950062/comusleslies1867epecurian_1.jpg)

Turkey, cranberry sauce, stuffing, family… Thanksgiving is a cluster of family traditions. But once upon a time, for some Americans, it was more like a carnival.

Modern Thanksgiving celebrations date back to around the Civil War, when Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation setting a specific day for Thanksgiving in November. However, Thanksgiving celebrations stretch back much farther than that in American history. One of the things modern Thanksgiving erased, writes historian Elizabeth Pleck, was its previous rowdy associations, which were pretty much the opposite of what the holiday is now.

For poor people, she writes, the holiday was “a masculine escape from family, a day of rule breaking and spontaneous mirth.” It wasn’t all fun and games, either: “Drunken men and boys, often masked, paraded from house to house and demanded to be treated,” she writes. “Boys misbehaved and men committed physical assaults on Thanksgiving as well as on Christmas.”

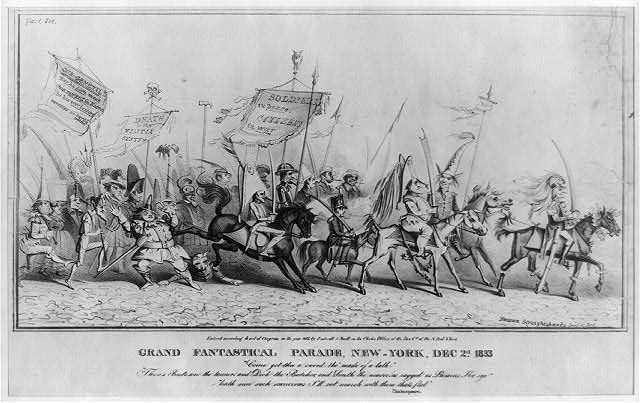

From this culture of “misrule” came the Fantastics. This group of pranksters, often dressed as women, paraded through the streets. “The Fantastics paraded in rural and urban areas of eastern and central Pennsylvania and New York City on Thanksgiving, New Year’s Eve and Day, Battalion Day, Washington’s Birthday and the fourth of July,” she writes. And unlike the loose groups of boys and men who middle and upper-class people feared, “Fantastical” parades were regarded as good fun.

"These were real processions, with some men on horseback and men in carts and men in drag," Pleck told The Washington Post's Peter Carlson. "They would march through New York and they would end up in the park, where there would be a rowdy, drunken picnic."

Slowly, though, middle- and upper-class people, who had influence with the police and the press, became afraid of any kind of street rowdiness and the subsequent crackdown stopped the parades. But the legacy of the Fantastics lived on, in the tamed treat-or-treat spirit of Halloween and in occasional parades in some places. Today, we think of the Thanksgiving parade as an orderly affair, but in the 19th century, historian Josh Brown told Carlson, "the notion of a parade was to participate."