Fish Don’t Do So Well in Space

The International Space Station’s resident fish shed light on life in microgravity

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/69/5b/695b16e9-0eb0-4921-827e-69f35456b951/670713main_aquatic1_lg.jpg)

Life in space is hard on the human body. The lack of gravity's pull can quickly take its toll—bone density declines, muscles deteriorate and more. But compared to a fish, humans have it pretty easy, Michael Byrne reports for Motherboard.

For several years, scientists working with the Japanese Space Agency (JAXA) studied the effects of life aboard the International Space Station for a small school of medaka fish. Also known as Japanese rice fish, medaka are small, freshwater fish native to Japan. And they are invaluable for space research. Not only are they easy to breed, but they are transparent, giving researchers a clear view at their bones and guts as they adjust to life in space, Jessica Nimon writes for NASA’s International Space Station Program Science Office.

It turns out that the effects of microgravity on medaka aren’t much different than our own—the effects just set in much faster. For humans, it takes at least ten days for the symptoms to start showing up, but according to a new study published in the journal Scientific Reports, the fish started losing bone density almost immediately upon arriving in orbit. Since humans and medaka grow their skeletons in similar ways, that gives scientists a good starting point to figure out how the process actually occurs, Byrne reports.

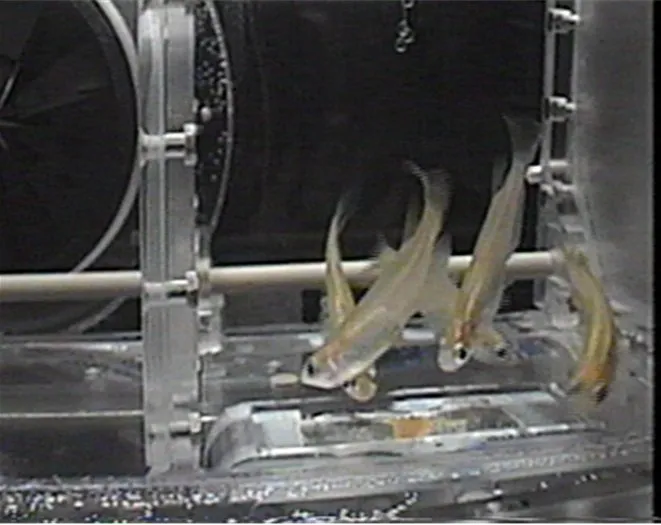

In order to get a closer look at how the fishes bodies reacted to life in space, the scientists genetically modified them so that two different types of cells would glow under different wavelengths of light. The first, osteoclasts, break down bone tissue as part of the process of repairing and maintaining any damage. The second, osteoblasts, create the matrices that bones form around, Byrne reports. As soon as the fish made it to the ISS, they went into a special tank designed for microgravity and were observed from a remote lab at Tsukuba Space Center using the two different fluorescent lights as their bodies adjusted to their new environment.

Because the fish reacted so quickly to their new living situation, the researchers were able to observe the effects of microgravity on their bodies almost in real time. Almost immediately, numbers of both types of cells increased noticeably when compared to an Earthbound control group, with certain genes going into action in ways not seen in normal gravity, Byrne reports.

While these findings are limited to this batch of lab-grown fish, it could eventually shed new light on the processes that govern how human bodies adapt to space as well as to typical human diseases like osteoporosis. For now, the researchers plan to continue their work with their next batch of fishy astronauts.