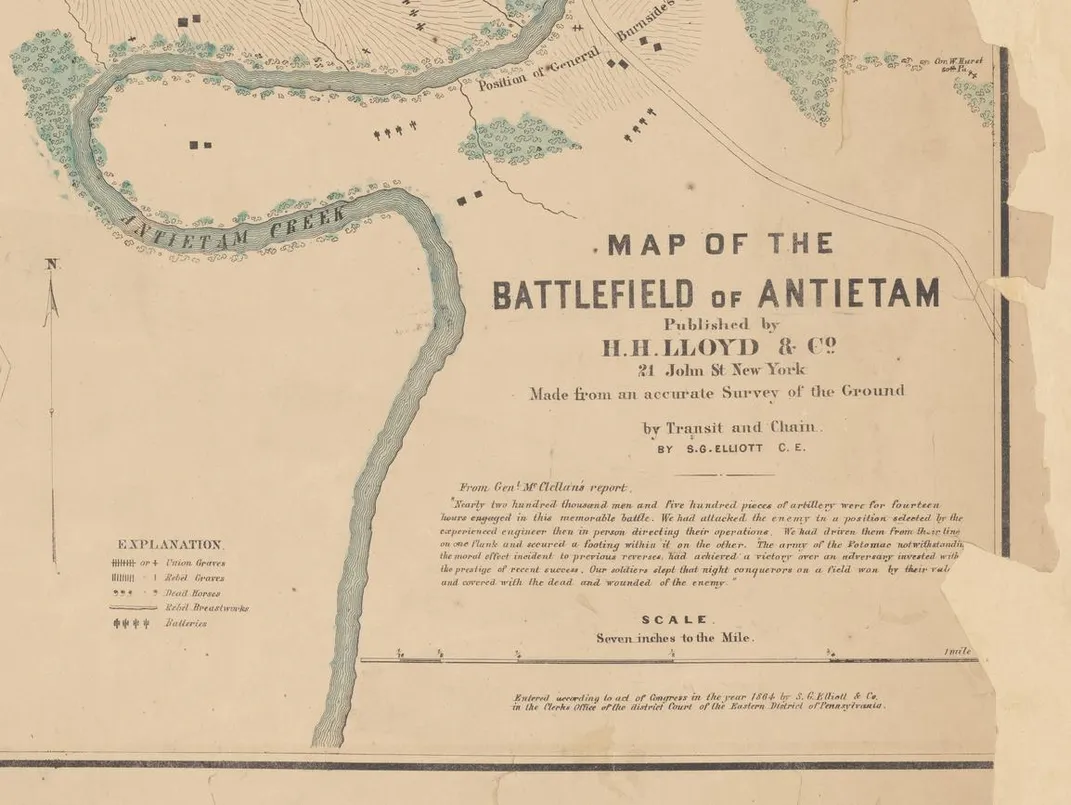

Forgotten Antietam Battlefield Map Shows Locations of Thousands of Graves

The Union and Confederate soldiers buried at the site of the 1862 clash were later moved to nearby cemeteries

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8b/2a/8b2aa639-b917-4f92-bad5-908bb14f44aa/2020_june18_antietammap.jpg)

The Battle of Antietam marked the single bloodiest day of the Civil War. During a 12-hour clash that started at dawn, more than 3,500 soldiers died, and another 17,300 were wounded. One in seven of these men later died of their wounds, according to the National Park Service, which manages the historic site of the September 17, 1862, battle. Nearly 1,800 went missing or were captured.

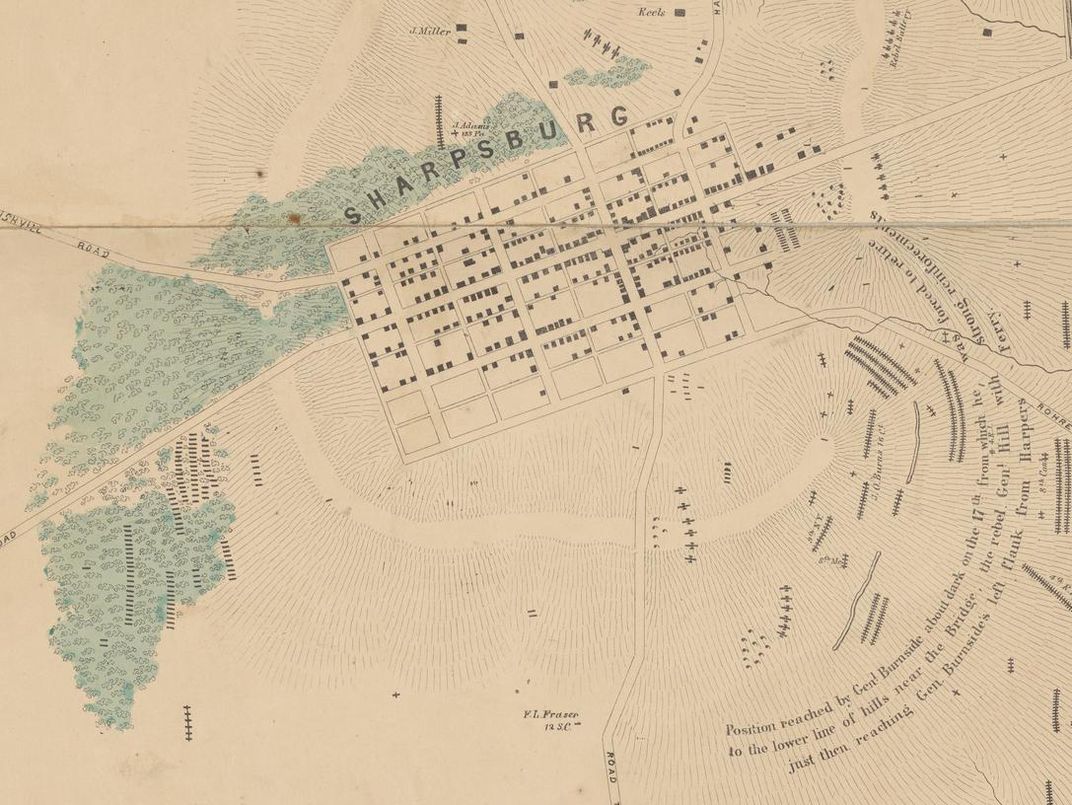

A newly rediscovered map created shortly after the fight offers a stark perspective on Antietam’s aftermath. As Michael E. Ruane writes for the Washington Post, the tattered piece of paper shows the locations of thousands of soldiers’ graves, reframing a patch of land in Maryland not as the site of “scenes of charge and countercharge, but as one vast cemetery.”

Historian Timothy Smith chanced upon the map while searching the New York Public Library’s (NYPL) digital collections for a similar one of the Gettysburg battlefield. Both charts were made by mapmaker Simon G. Elliott.

“I searched for ‘S.G. Elliott’ and ‘Gettysburg,’ then downloaded the results, so I could look at them in detail,” Smith tells Clint Schemmer of the Culpeper Star-Exponent. “When I opened up the file, I was utterly taken aback, and knew I was looking at something extraordinary.”

Speaking with the Post, Smith adds, “It’s a visual representation of the carnage from the battle. It’s startling to look at.”

The map shows the locations of some 5,800 graves scattered across a 12-square-mile area. It uses different notations for Union and Confederate soldiers and, in some cases, even specifies the deceased’s regiment or brigade. Around 45 of the notations include the names of individual soldiers.

“Every one of us who’s looked at this absolutely flips out,” says Garry Adelman, chief historian at the American Battlefield Trust, to the Post. “This will reverberate for decades.”

Elliott created the map about two years after the battle—around the time he traveled east from California to lobby Congress on a railroad bill, per the Culpeper Star-Exponent. Historians are unsure exactly how or why Elliott produced the Gettysburg and Antietam maps, but Smith tells the Post that he may have drawn on surveys conducted by locals.

The Union Army arrived at Antietam in hopes of halting a Confederate invasion of Maryland. Though the day ended in a draw, the Confederate troops retreated to Virginia soon after.

According to the National Park Service, burial details interred the dead in graves ranging from “single burials to long, shallow trenches accommodating hundreds.” Beginning in 1866, Union soldiers were moved from their temporary resting place on the battlefield to the newly established Antietam National Cemetery. Confederate casualties were reburied in other nearby cemeteries.

Some of the graves marked on Elliott’s map of Antietam match photographs taken by Alexander Gardner, whose images of dead soldiers and burials were displayed in New York the month after the battle.

“This discovery reveals truths about the Battle of Antietam lost to time,” Adelman tells the Culpeper Star-Exponent. “It’s like the Rosetta Stone: By demonstrating new ways that primary sources already at our disposal relate to each other, it has the power to confirm some of our long-held beliefs—or maybe turn some of our suppositions on their heads.”

In an email to the Post, NYPL map division curator Ian Fowler said the library likely acquired the map when it was published in New York in 1864. Employees had long been aware of the chart’s rarity and importance, but it was only digitized recently. (The library’s map digitization project ran from 2015 to 2018 and made more than 3,000 antique charts available online.)

The Antietam map has a few errors: The 1st Minnesota infantry is misidentified as the 1st Maryland, according to the Post, and a G.D. Berry is likely actually George O. Berry. Geo. Dow, meanwhile, probably refers to George Dorr. Despite these mistakes, the map may be one of the earliest representations of the entire Antietam battlefield, says Adelman, and “[o]n a scale from one to 10 of Civil War battlefield discoveries … I’d call it a 9.5.”

Speaking with the Culpeper Star-Exponent, Smith explains, “Elliott deserves credit for compiling this valuable information and having it published. It may well be the closest historians come to understanding the physical aftermath of America’s costliest battles.”