Rosa Bonheur’s Hyper-Realistic Animal Scenes Transfixed 19th-Century Europe

The Musée d’Orsay recently announced plans to dedicate a fall 2022 exhibition to the trailblazing French artist

:focal(400x274:401x275)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d1/ab/d1ab596b-8c27-406b-aa6d-91876a6ee0f8/cows_and_such.jpg)

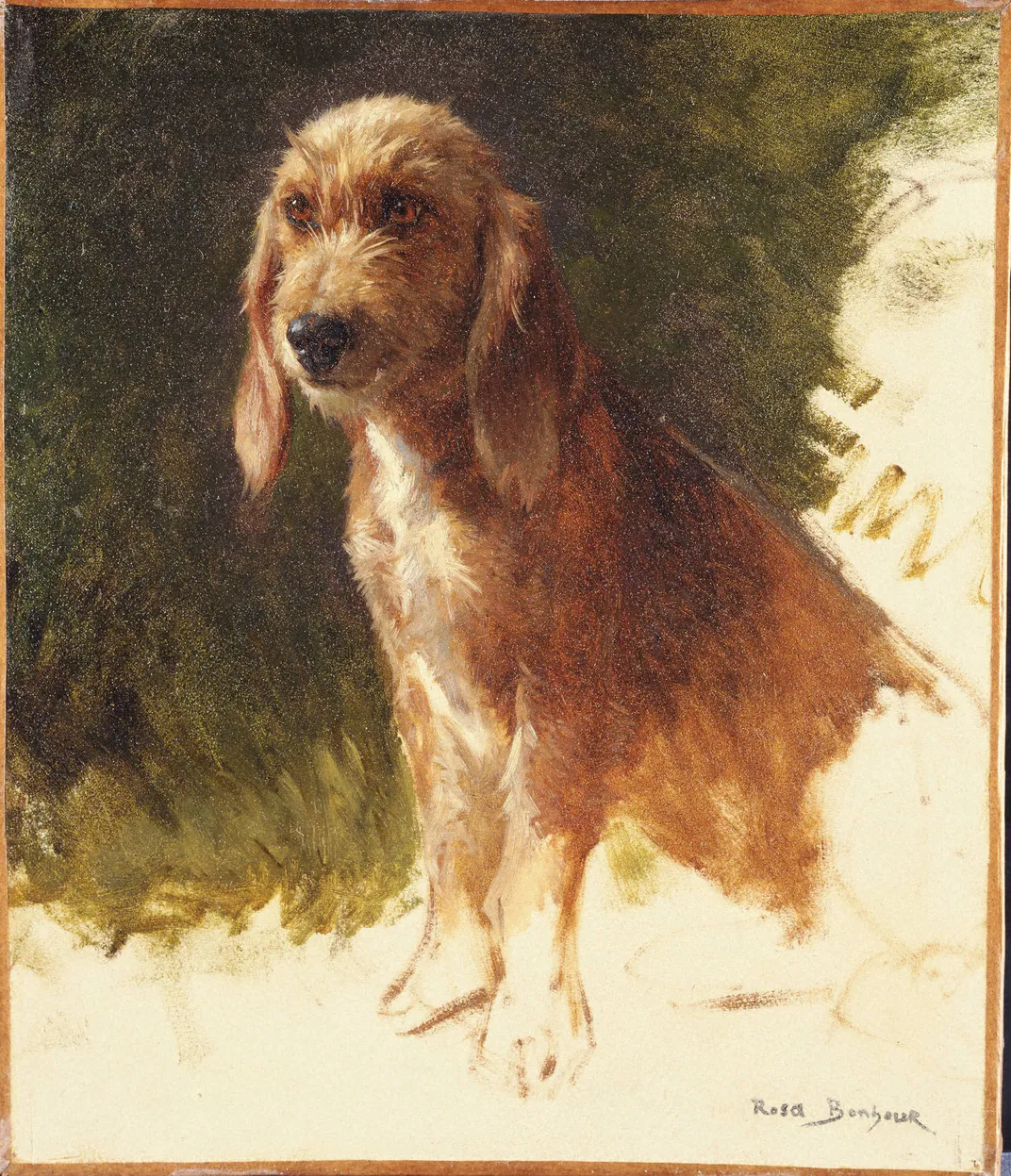

During her lifetime, Rosa Bonheur’s stunningly realistic paintings of horses, oxen, lions and other animals garnered widespread critical acclaim. After her death in 1899, however, the French artist—once celebrated as one of the great female painters of the 19th-century—slipped into obscurity.

Today, most Parisians know Bonheur through the few bars and restaurants that bear her name. But an upcoming exhibition at one of the French capital’s most prominent museums is poised to bring the artist some long-overdue recognition. Come fall 2022, reports Faustine Léo for Le Parisien, the Musée d'Orsay will pay homage to Bonheur with a groundbreaking exhibition featuring a number of previously unseen works.

Katherine Brault, a 58-year-old former communications specialist who has dedicated the past several years to championing Bonheur’s legacy, convinced the Paris gallery to host a comprehensive exhibition of the artist’s work. The museum hosted a display of her caricatures earlier this year and counts Ploughing in Nevers (1849), a lively landscape featuring farm animals, among its collections, but the upcoming show will be its first full-scale exhibition dedicated to Bonheur.

“[The exhibition] won’t be a retrospective,” Brault tells Le Parisien, per Google Translate. “We will show the hidden sides of Rosa Bonheur, such as her passion for opera and her relationships with the composers of the time.”

As Elaine Sciolino wrote in the November issue of Smithsonian magazine, Brault purchased Bonheur’s beloved chateau in 2017 and is now working to convert the venue into a museum. Last year, the French government awarded Brault €500,000 (around $605,000 USD) to help preserve the historic property.

Bonheur was born in Bordeaux in 1822. When she was 7, her family moved to Paris, where her father, Raymond, left his wife and four children to live with a utopian socialist sect. Bonheur’s mother, Sophie, taught piano lessons and took sewing jobs to make ends meet but died when her daughter was just 11. The family was so impoverished that they had to bury Sophie in a pauper’s grave; Raymond, a struggling artist, returned to support his children following his wife’s death.

Despite these hardships, Bonheur soon emerged as a respected artist. She began her art education as a teenager, copying paintings at the Louvre under her father’s tutelage and studying living animals firsthand to gain “an intimate knowledge of animal anatomy,” according to Encyclopedia Britannica. At age 19, she showed paintings of rabbits, goats and sheep at the Paris Salon, and though these works “attracted no attention,” in the words of the International Herald Tribune’s Mary Blume, the young artist had established herself as a formidable figure in the French cultural sphere by 1845.

In 1865, Bonheur became the first woman to receive the Légion d’Honneur for achievement in the arts. Presenting the award, Empress Eugénie, wife of Napoleon III, declared, “Genius has no sex.”

Brault tells Le Parisien that Bonheur “is comparable to Leonardo da Vinci [with] his scientific approach to drawing. She brought a new perspective to the animals, which for her already had a soul.”

The Horse Fair (1852-55), a dynamic, extremely detailed work that currently hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is arguably Bonheur’s best-known painting. Lauded by one American periodical as “the world’s greatest animal picture,” it was reproduced and sold as a print across Britain, continental Europe and the United States. Even Queen Victoria admired the work, attending a private viewing of the equestrian scene during one of the artist’s visits to England.

Bonheur dedicated her life to her career, eschewing traditional constraints by insisting on her independence. As an adult, she lived by her own rules, dressing in men’s clothes, smoking cigars and living with female partners.

“Women’s rights!—women’s nonsense!” Bonheur said in the 1850s, as quoted by Tom Stammers of the London Review of Books. “Women should seek to establish their rights by good and great works, and not by conventions ... I have no patience with women who ask permission to think!”

This forceful personality separated Bonheur from other female artists of her time. As feminist art historian Linda Nochlin wrote in a 1971 issue of ARTnews, she “is a woman artist in whom, partly because of the magnitude of her reputation, all the various conflicts, all the internal and external contradictions and struggles typical of her sex and profession, stand out in sharp relief.”

Writing in the London Review, Stammers says it’s “hard to exaggerate Bonheur’s fame in the mid-19th century, or the adulation she inspired.”

Shortly after the artist’s death in 1899 at age 77, her sketches and preparatory drawings sold for an “unprecedented” 1,180,880 francs. But her work fell out of favor with the rise of Impressionism and more abstract art forms, and she has only enjoyed a resurgence of attention in recent years.

In addition to Brault’s planned museum and the upcoming Musée d'Orsay exhibition, Bonheur’s work makes a brief appearance in Netflix’s hit miniseries “The Queen’s Gambit.” (The main character’s adoptive mother has Bonheur prints hanging in her home.) Per artnet News’ Ben Davis, the central chess prodigy’s character arc “retraces the rough contours of Bonheur’s life,” from her all-consuming passion for a creative pursuit to her desire for independence.

“Rosa Bonheur is being reborn,” Brault’s daughter, Lou, who is helping her mother convert the chateau, told Smithsonian earlier this year. “She is finally coming out of the purgatory into which she was unjustly thrown.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/97/c8/97c84385-1f6b-4ab4-82fb-03ce4e71c1fe/bonheur-haggin-gathering-for-the-hunt-color-corrected.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d7/96/d7965a39-99b4-4c8c-8622-148b51a2e4b1/rosa_bonheur_horse_fair_1835_55.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b7/d9/b7d92bd4-98b4-4f63-91f3-9e3c00da3c6a/rosa_bonheur_with_bull__by_e_l_dubufe.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e9/86/e98646fd-04f5-4b86-bb98-48cd5e76fd2f/anna_klumpke_-_portrait_of_rosa_bonheur_1898.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)