France’s Senate Requires That Notre-Dame’s Iconic Spire Be Rebuilt ‘Exactly as It Was’

The bill contradicts an earlier call for proposals to replace the fallen tower with a more modern aesthetic

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4a/bb/4abbeff5-64c3-49ba-a6f2-2d41e7f64e8f/gettyimages-1145305668.jpg)

Days after an inferno blazed through Notre-Dame this April, destroying the cathedral’s iconic spire and two-thirds of its wooden roof, French Prime Minister Édouard Philippe announced an international competition aimed at replacing the fallen tower with a new “spire suited to the techniques and challenges of our time.” But the inventive redesigns architects proposed aren’t likely to grace the Parisian skyline any time soon: As Le Monde reports, France’s Senate voted Monday to restore the Parisian cathedral to its “last known visual state” prior to the fire, directly contradicting other government officials’ hopes for a more contemporary design.

According to the Local France, the issue of whether to rebuild Notre-Dame’s spire exactly as it was or in an entirely new style has emerged as a “political battleground” for the already polarized country. French President Emmanuel Macron, facing criticism for rushing to complete construction in time for the Paris 2024 Olympics rather than acknowledging the lengthy timeline realistic for rebuilding, is open to the idea of a “contemporary architectural gesture.” Mayor Anne Hidalgo, meanwhile, has spoken out in favor of an identical restoration.

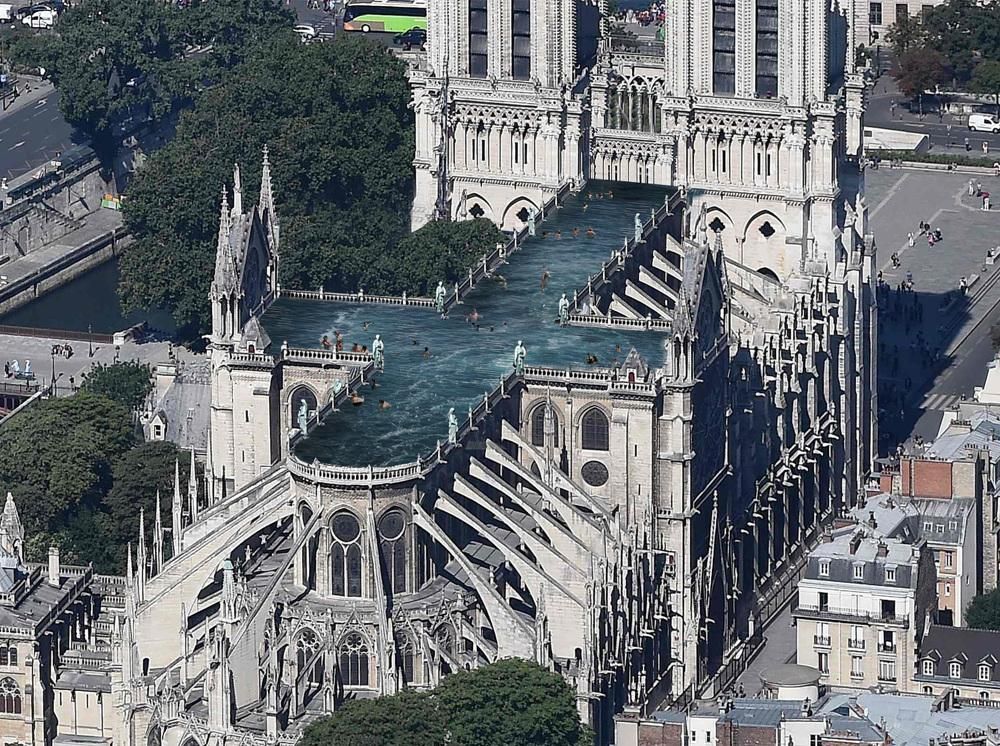

Architects who embraced the idea of a modern design envisioned a roof and spire constructed out of stained glass, recycled ocean plastic, copper and stainless steel, crystal, or even gold leaf-encrusted carbon fiber. At the more audacious end of the spectrum, one proposal suggested transforming the roof into a cross-shaped swimming pool, while another advocated for turning the area underneath the roof into a greenhouse sanctuary for birds and insects.

In the French Senate, advocates for a reconstructed—not reimagined—spire prevailed. As the Local France explains, the Senate bill amends legislation previously passed by the French National Assembly. In addition to requiring a lookalike spire, the legislation removes a clause that would have allowed the government to override heritage, environmental and planning regulations. It calls for the creation of a Ministry of Culture sub-agency to oversee restoration but keeps Macron’s 2024 deadline.

A YouGov survey of French residents conducted in the aftermath of the fire revealed a slim majority (54 percent) in favor of restoring Notre-Dame to its last known state; 25 percent called for a revamped design, while 21 percent had no opinion on the matter.

For all the debate over its reconstruction, the roughly 300-foot, lead-covered wood spire was not, in fact, an original element of Notre-Dame. Designed by French architect Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc in the mid-1800s, the tower replaced an earlier spire removed between 1786 and 1791, as Meagan Flynn writes for the Washington Post. The cathedral’s attic was even older, dating to the 13th century.

According to Gareth Harris of the Art Newspaper, the Senate legislation stipulates that conservation “restores the monument in the same way visually as before.” The bill also states, “If the [conservation team] uses materials different from those in place prior to the disaster, it [should] publish a study giving the reasons for these changes.”

If Notre-Dame’s roof were rebuilt exactly as it existed prior to the blaze, 3,000 sturdy oak trees would be needed to replace it in its entirety, reports CBS News’ Haley Ott. Given the lack of suitable forests remaining in Europe today, this wood requirement poses a stark logistical obstacle, although Emily Guerry, a medieval historian from England’s University of Kent, tells Ott that the Baltic states may hold enough “very tall, very old trees” for the project.

It’s also worth noting, Guerry says, that the original limestone used to build the cathedral was quarried and assembled by hand during the 12th century. If contemporary builders hope to maintain the building’s “homogenous” look, they must follow the same painstaking process.

For now, the rebuilding bill remains in limbo. Both France’s Senate and the National Assembly must agree on the wording of the final version before it can become law.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/db/73/db73dcf2-3fca-4b07-b11b-2b59e1f54f8f/i-5c-see-6-concepts-for-the-future-of-notre-dame.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)