Smithsonian Curator Weighs in on Legacy of Frank Robinson, Barrier-Breaking Baseball Great

Robinson was one of the great all-time home run hitters and made history when he became the manager of the Cleveland Indians

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/56/dc/56dcfb7f-ae57-4bb1-bb7b-14d80a6329c4/gettyimages-78600700.jpg)

During his 21 seasons as an outfielder, first with the Cincinnati Reds and later with the Baltimore Orioles among other teams, Major League Baseball hall of famer Frank Robinson accumulated some of the best stats in baseball history. He hit 586 career home runs, was named an All-Star 14 times and remains the only player to earn the Most Valuable Player award in both leagues, receiving the title in 1961 for his work with the Reds and in 1966 while playing for the Orioles, respectively.

But it’s his work in the dugout that will especially go down in history. Robinson, who died at his home outside Los Angeles at the age of 83 on Thursday, February 7, was the first African-American manager of a major league team, taking the helm of the Cleveland Indians in the spring of 1975.

Damion Thomas, curator of sports at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, says Robinson’s transition to the manager's seat helped fulfill one of Jackie Robinson’s dreams. Before his death in 1972, Jackie was adamant that for segregation in baseball to truly be over, African Americans needed to be allowed into management and ownership. Robinson’s move in 1975 was a fulfillment of that dream, part of the first wave of African Americans moving into management positions in the corporate world, academia and elsewhere.

As a player, Robinson also broke boundaries. During his 1966 MVP season for the Orioles, Robinson earned the American League triple crown, hitting with a .316 average, bashing 49 home runs, batting in 122 runs and scoring 122 times himself, all of which helped the Orioles achieve their first World Series win, Richard Justice at MLB.com reports. He was voted into the Hall of Fame in 1982.

Thomas points out that Robinson was one of the first players in the post-segregation era to show African Americans could play “long ball,” or be a home-run sluggers. African American players coming out of the Negro Leagues were said to play “small ball," specializing in getting on base and stealing, not knocking the ball over the fence. Robinson was part of a group of players, including Willie Mays and Hank Aaron, who changed that perception forever.

“When Frank Robinson retired, only Babe Ruth, Willie Mays and Hank Aaron had hit more home runs,” Thomas says. “I think he’s deserving of being held in that higher esteem. He held records that others didn’t surpass until the steroid era.”

Beginning as early as 1968, Robinson turned his eye toward management. That year, according to Richard Goldstein at The New York Times, he began coaching a team in a winter league in Santurce, Puerto Rico, learning the ropes in the hopes of eventually managing an MLB team. In 1974, he got his chance when he was traded to the Indians, wher he was promoted to player/manager for the 1975/76 season, coaching the team and continuing his work on the field as a designated hitter.

When he first took the field as manager, Robinson knew he was making history. “It was the biggest ovation I ever received, and it almost brought tears to my eyes. After all the years of waiting to become a big league manager — ignored because so many team owners felt that fans would not accept a black manager — I was on the job and people were loudly pleased,” he reflected in his memoirs.

Robinson coached through 2006, with a mixed record, serving stints with the San Francisco Giants, Baltimore Orioles, Montreal Expos and Washington Nationals. Though none of his teams went on to play in the World Series, he was voted American League manager of the year in 1989. He went on to finish his career working in a variety of positions in the front office of Major League Baseball.

It’s hard to imagine Robinson was happy with the progress made in the sport in the last 45 years. According to Thomas, in that span of time only around 10 African Americans have served as Major League Baseball managers, and few have served at executive levels in the sport, something Robinson fought hard to redress during his career on and off the field.

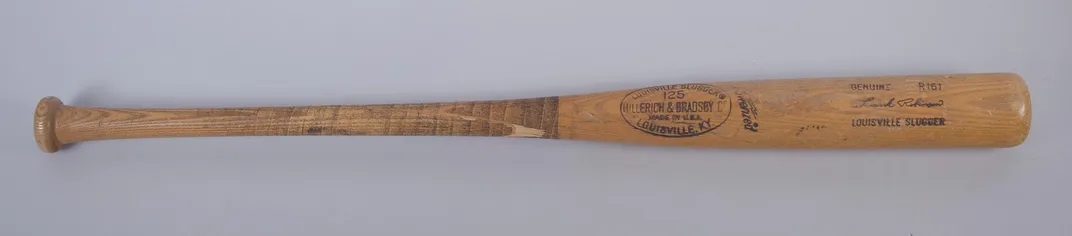

One of Robinson’s game bats is now on display at the NMAAHC next to a bat used by Mays and a silver bat awarded to 1997 batting champion Tony Gwynn. Thomas says he likes to show the bat, which is larger and heavier than modern bats, to other major league players because it gives him a chance to talk about one of baseball’s most significant hitters.

Though Robinson wasn’t necessarily on the front lines of the Civil Rights struggle, Thomas, who gave him a tour of the National African American History and Culture just last summer, says he was very aware of his legacy.

“He said something interesting,” Thomas remembers. “He told me he thought of Jackie Robinson every day he put on his uniform. He not only saw himself as a benefactor of Jackie Robinson and other players, but saw himself as a guardian of that legacy. And as someone who had to work to expand those opportunities, and he certainly did that as a player and a manager and even in the front office.”