Fredericksburg’s Slave Auction Block Will Be Moved to a Museum

Curators plan on preserving graffiti added by Black Lives Matter protesters

:focal(1399x903:1400x904)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/66/6566ee05-33c0-4d3a-a600-9afcc6ba9404/document.jpeg)

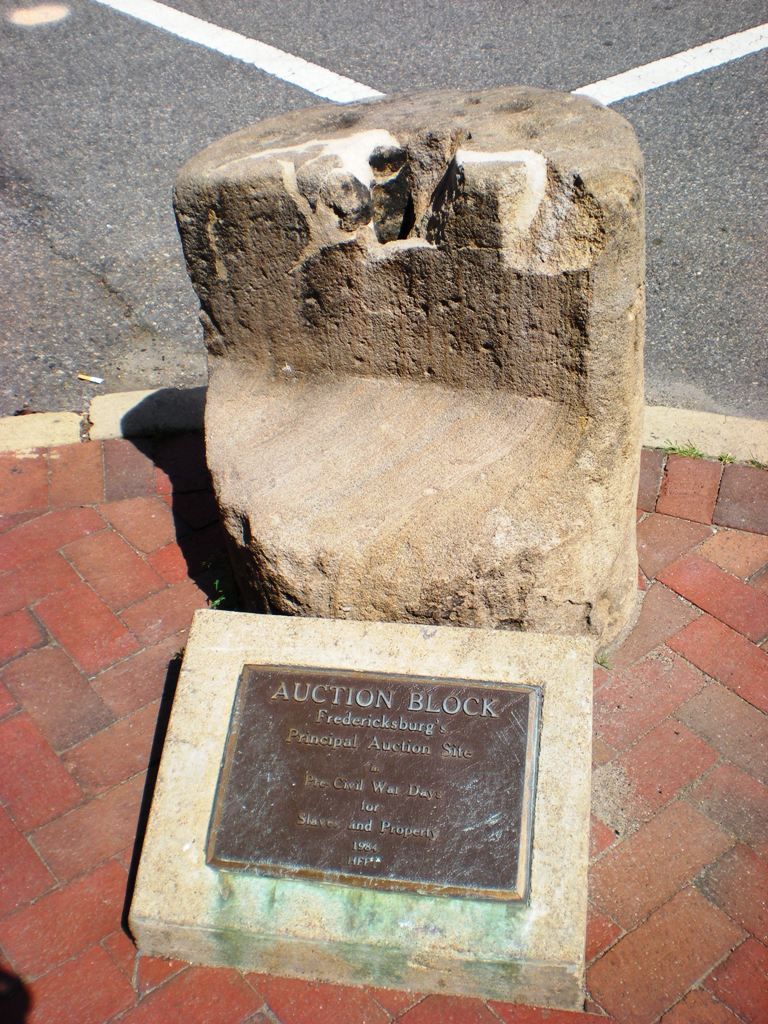

In early June, officials in Fredericksburg, Virginia, removed a stone block that commemorates the auctioning of enslaved people from a public sidewalk. Now, reports Cathy Jett for the Free Lance-Star, the controversial artifact is set to go on view in a local museum with added contextualization.

The 800-pound block of sandstone once stood at the corner of William and Charles Streets in the city’s historic center. Beginning in the 1830s, enslavers routinely auctioned off groups of enslaved African Americans near the site.

As Michael S. Rosenwald wrote for the Washington Post in June, the block and its painful history have been the subject of debate for decades. This year, the stone came under renewed scrutiny as protests against racial injustice and police brutality swept the country. During marches in Fredericksburg, protesters reportedly spray-painted it and chanted, “Move the block!”

City officials voted to remove the stone last year. But lawsuits and the Covid-19 pandemic delayed the actual event until this summer, notes Jett in a separate Free Lance-Star article. In the coming months, a temporary panel called “A Witness to History” is slated to be installed where the block once stood.

Per the Free Lance-Star, the stone will go on display at the Fredericksburg Area Museum (FAM) by mid-November at the earliest. Eventually, the museum plans to feature the block in a permanent exhibition about Fredericksburg’s African American history.

Sara Poore, president and CEO of FAM, tells the Free Lance-Star that the stone will be cleaned of years of accumulated grime. Protesters’ graffiti, however, will remain intact.

“We will also discuss the recent events and the impact the stone has had on the conversation” about racism and slavery in local history, Poore adds. “It is our goal to use the stone as a springboard for community conversations.”

Fredericksburg City Councilor Charlie Frye began advocating for the block’s removal in 2017, after a “Unite the Right” rally in neighboring Charlottesville turned deadly. That same year, a local NAACP chapter also called for the stone’s removal, calling it a relic of “a time of hatred and degradation,” per the Associated Press.

When Frye—the only African American member of the council—first raised the question of the block’s fate, all of his peers voted to keep it in place with added historical context.

After the vote, the city hired an outside nonprofit, the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, to investigate the historical site. When the council held a second vote on the issue in June 2019, members voted 6-1 in favor of the block’s removal. Councilors officially approved the move in November.

To lift the massive stone block, workers used “a custom-designed pallet,” stabilizing straps, weights and mechanical equipment, according to a statement.

An archaeological survey conducted by the city in 2019 found no direct evidence that the stone itself was used as an auction block. But it concluded that the block “may have been used as a sign post associated with the presentation of data on upcoming auctions and events.”

The block was likely put in place in the 1830s or 1840s, when the nearby United States Hotel was under construction. Later known as the Planter’s Hotel, the inn was a well-established hub for the auction of enslaved individuals throughout the 19th century.

Per the report, the earliest record of a sale taking place near the hotel appears in a November 20, 1846, edition of the Richmond Enquirer, which advertised the auction of 40 enslaved people. The largest recorded sale took place on January 3, 1854, when enslavers sold 46 individuals on the site.

“The institution of slavery was central to the [Fredericksburg] community prior to the Civil War,” John Hennessy, the city’s chief historian, told CNN’s Ellen Kobe in June. “… The block became an embodiment of the present and past pain in this community.”

Speaking with CNN, Frye observed, “I think racist folks loved it, historians understood it, and black people were intimidated.”

Today, the stone bears red, white and green spray paint left over from this summer’s protests.

Poole told CNN that she strongly recommended curators preserve the spray paint.

“[T]he graffiti itself tells a story,” she added. “By cleaning it, you erase history.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)