How Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera Defined Mexican Art in the Wake of Revolution

A touring exhibition now on view in Denver traces the formation of Mexican modernism

:focal(860x434:861x435)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/18/27/18270e36-f6e6-4da2-9ffb-85c9a9b60e8b/testing23.jpg)

In early 20th-century Mexico, a prolonged series of civil wars and agrarian uprisings ended a dictatorship and established a constitutional republic. The Mexican Revolution, as the struggle came to be known, also occasioned a dramatic shift in the country’s art world: Emboldened and inspired, painters such as married couple Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera began to experiment with new styles and themes of Mexican identity.

Now, exactly 100 years after the fighting subsided, a traveling exhibition currently on view at the Denver Art Museum (DAM) examines how political revolution gave rise to a Renaissance period in Mexican modern art. Titled “Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and Mexican Modernism,” the show unites more than 150 works by luminaries including the eponymous couple, María Izquierdo, Carlos Mérida and Lola Álvarez Bravo.

Per a museum statement, “Mexican Modernism” traces how artists in a postrevolutionary country derived inspiration from Mexico’s Indigenous cultures and colonial past to “[project] a visionary future.”

As exhibition curator Rebecca Hart tells 303 magazine’s Barbara Urzua, “The Mexican modernists gave visual identity to a new nation of Mexico and that identity incorporated aspects of ancient Mexican aesthetics and the most modern art styles.”

Most of the works featured in the show are on loan from the collection of Jacques and Natasha Gelman, European expatriates who moved to Mexico separately prior to the start of World War II. Jacques was an influential producer of Mexican films, and after the couple’s wedding in 1941, the Gelmans became key collectors of the country’s flourishing art scene.

One of the works on view in the exhibition is Izquierdo’s Naturaleza Viva, or Living Nature (1946), which depicts typical Mexican produce and a conch shell in a dream-like landscape. Izquierdo, like many of her peers, demonstrated a strong interest in both symbols of Mexican folklore and the surreal quality associated with magical realism.

Another featured painting—Mérida’s abstract Festival of the Birds (1959)—demonstrates the diversity of thought among artists working in Mexico at the time. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, Mérida, a Guatemalan artist who lived in Mexico, created geometric abstractions influenced by both European modernism and ancient Maya art.

“Mexican Modernism” also includes seven of Kahlo’s self-portraits, which have become famous in recent decades for their rich, thought-provoking explorations of gender, trauma, identity and nationality.

In Diego on My Mind (1943), Kahlo depicts herself wearing a traditional headdress from Tehuantepec, a city in the state of Oaxaca. A small portrait of her on-again off-again husband, Diego, decorates her forehead, and thin tendrils resembling roots extend in all directions from her serious gaze.

“Frida is deeply psychological,” Hart tells the Denver Gazette’s Jennifer Mulson. “Who do you understand best but yourself?”

Though Kahlo was long associated mainly with her husband, feminist scholarship in the 1970s helped to establish her artistic legacy as deeply influential in its own right. In recent years, public interest in the artist’s life and work has skyrocketed.

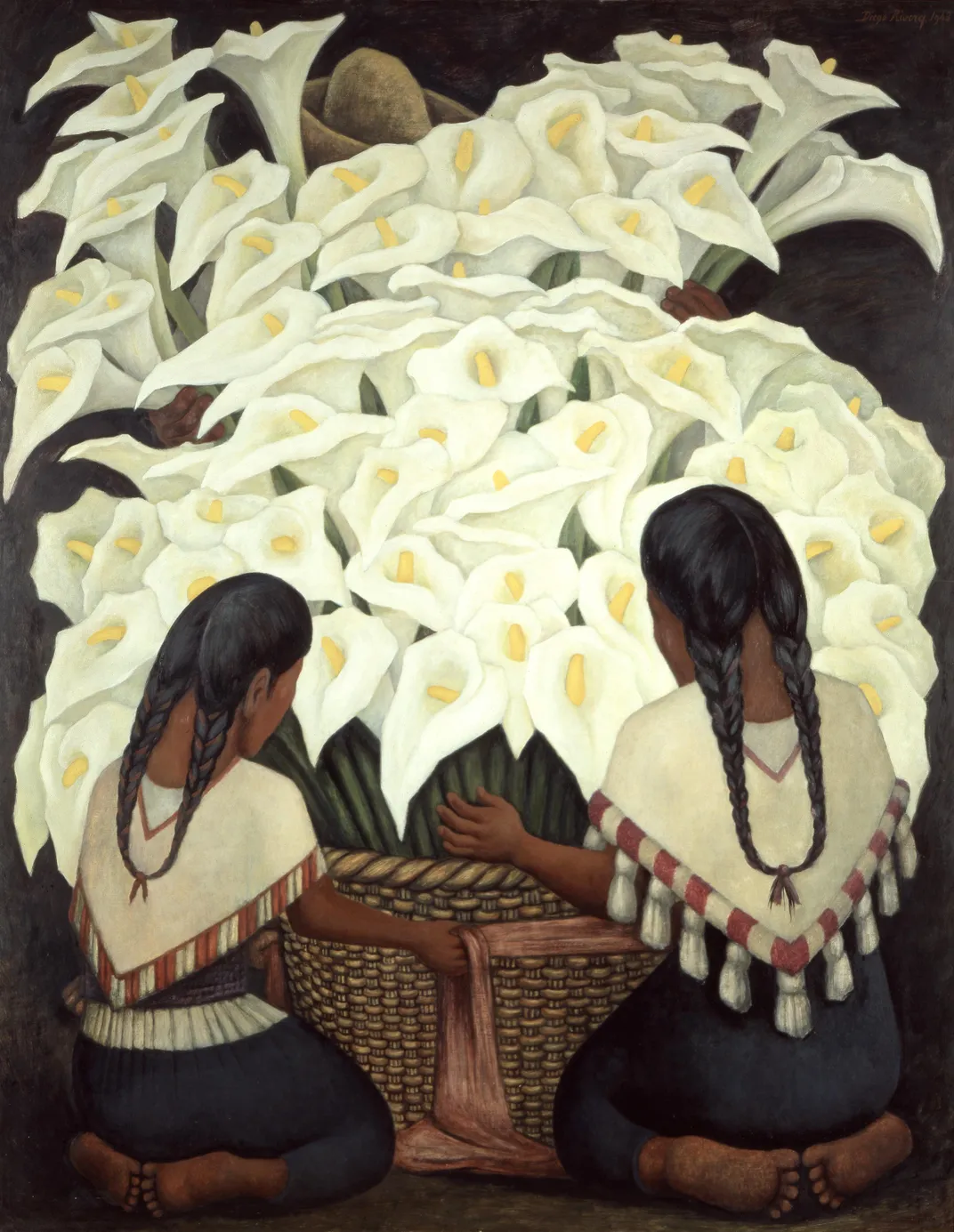

Writing for Denver art magazine Westword, critic Michael Paglia deems the exhibition’s opening image, Rivera’s iconic Calla Lilly Vendor (1943), a “showstopper.” The painting, which depicts Indigenous women kneeling away from the viewer and organizing a glorious set of white lilies, demonstrates Rivera’s progressive social interest in deifying ordinary labor and quotidian Mexican life.

Rivera, alongside contemporaries David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco, also participated in the renowned Mexican muralist movement, a state-led effort that aimed unify the divided country through large-scale, nationalist murals.

Kahlo, Rivera and their contemporaries existed at the center of bohemian, vibrant intellectual circles that thrived in Mexico City in the post-war decades. Both were members of the Mexican Communist Party and deeply invested in the political movements of their time. Kahlo even had a brief affair with Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky, as Alexxa Gotthardt noted for Artsy in 2019.

“They were politically, socially and intellectually engaged,” Hart tells the Gazette. “Their house, La Casa Azul, south of Mexico City, became a center where people exchanged ideas. That was very instrumental in the birth of Mexican modernism.”

“Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and Mexican Modernism” is on view at the Denver Art Museum through January 24, 2021.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)