A few weeks after her June 17, 1943, wedding, a young Jewish artist named Charlotte Salomon entrusted her friend and doctor, Georges Moridis, with a trove of carefully wrapped papers.

“Keep these safe,” she said. “They are my whole life.”

Salomon’s directive was far from an exaggeration. As Toni Bentley writes for the New Yorker, the bundles contained nearly 1,700 paintings and text-overlaid transparencies created by the 26-year-old German native during a frenzied outpouring of creative energy. The artist’s decision to part ways with her deeply personal oeuvre proved prescient: In late September, she and her husband, Alexander Nagler, were detained in France by the occupying Nazi forces and deported to Auschwitz. Salomon, then five months pregnant, was murdered in the gas chambers upon arrival.

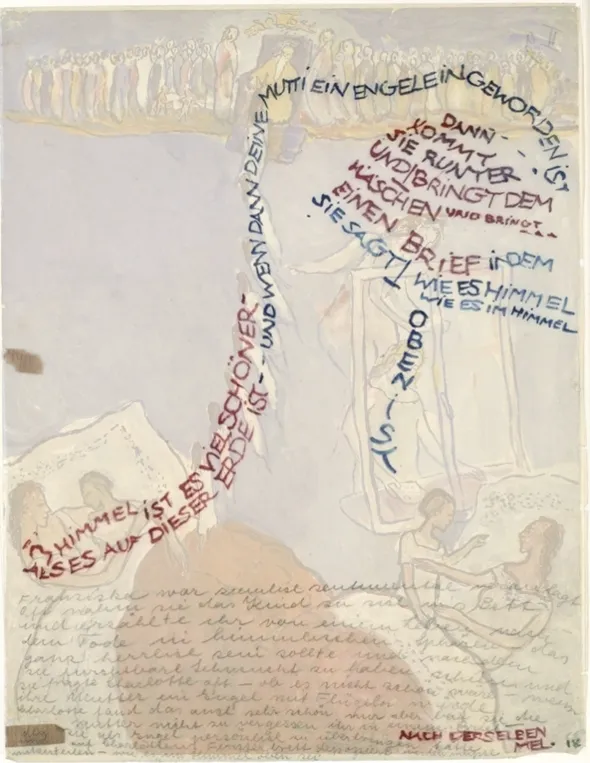

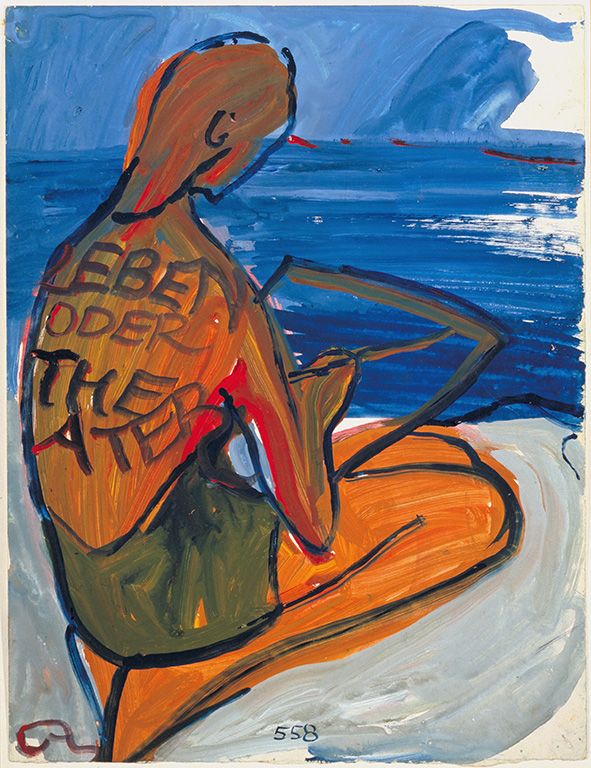

Part autobiography, part musical composition and part dramatic script, the works saved by her doctor—organized into a sweeping collection their creator titled Life? or Theatre?—trace both Salomon’s personal story and the looming threats she faced as a Jewish refugee living in France. A new exhibit at the Jewish Museum London, “Charlotte Salomon: Life? or Theatre?,” unites 236 of these paintings, 50 of which have never before been displayed in the United Kingdom, in a triumphant celebration of endurance against all odds.

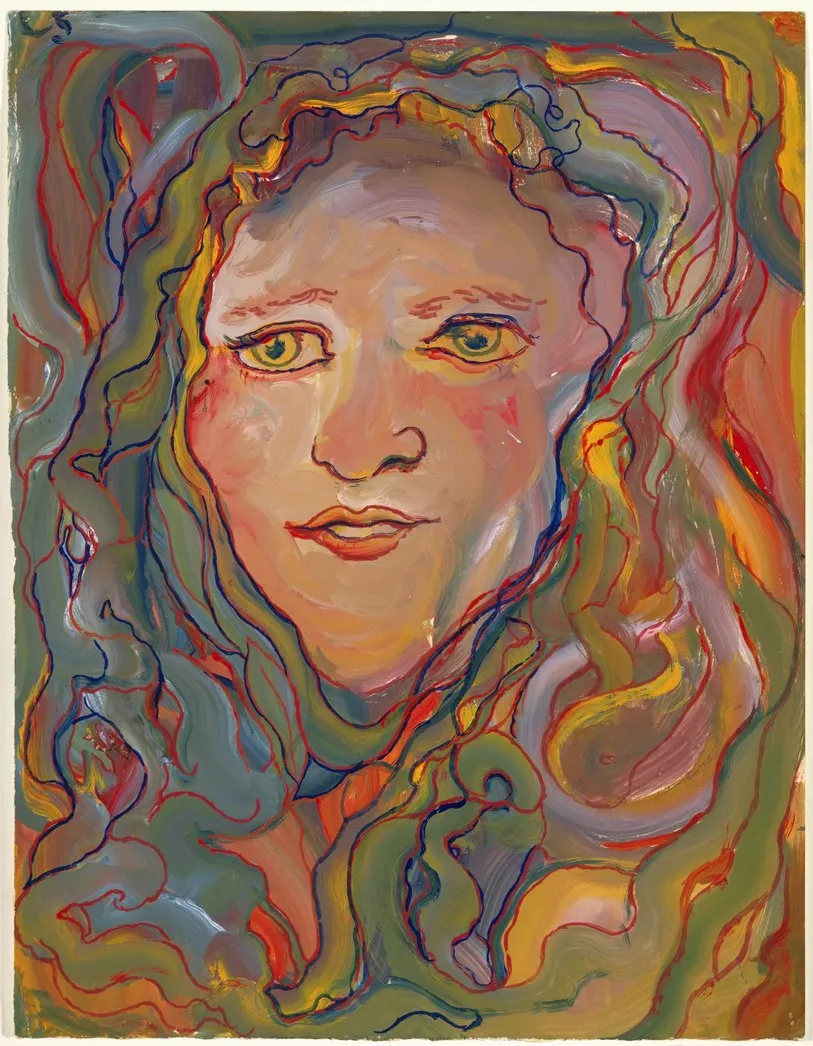

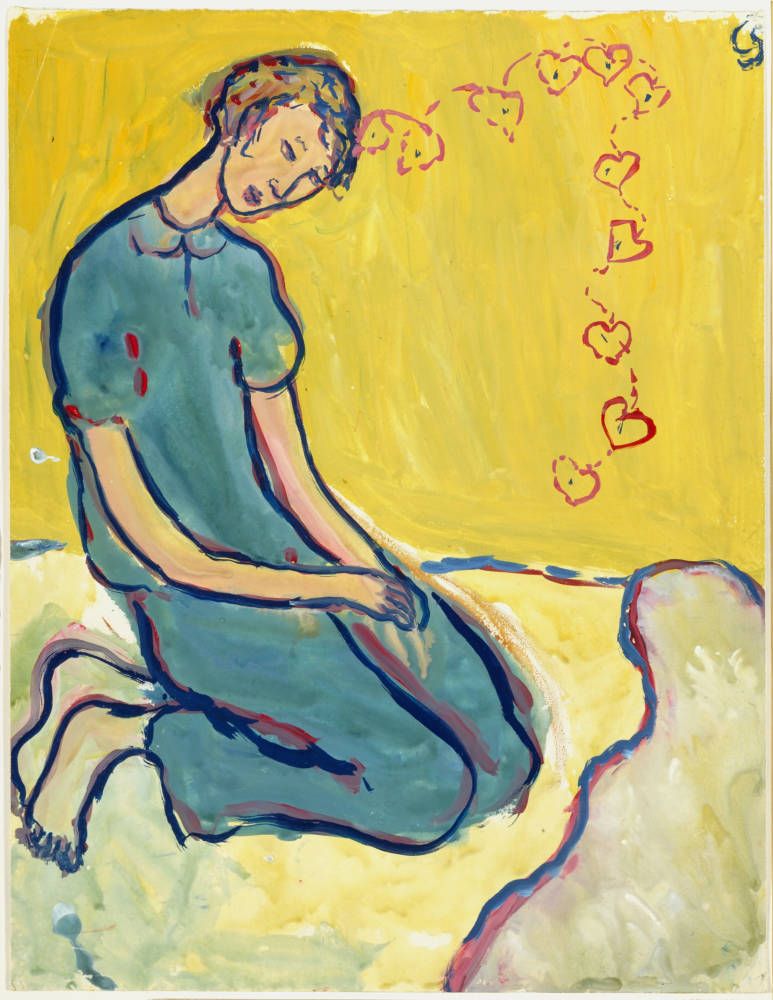

Salomon, born to an upper middle-class German family in 1917, anchors her work in the past. Annotated with text and even musical citations, the paintings chart the story of a thinly veiled stand-in of the artist named Charlotte Kann. They touch upon the real-life family stories of her aunt’s 1913 suicide and her parents’ World War I courtship before addressing her own life, including her mother’s suicide in 1926. Salomon acknowledges the trauma of her mother’s death, painting an 8-year-old version of Kann standing in front of a tombstone, but nevertheless displays what the Guardian’s Jonathan Jones deems “an irrepressible capacity for happiness.”

In 1930, Salomon’s father, Albert, married a singer named Paula Lindberg. The then-adolescent girl and her new stepmother forged a close bond. Through Lindberg, Salomon also grew close to singing instructor Alfred Wolfsohn, with whom she later had a close and potentially sexual relationship. According to Bentley, Life? or Theatre? features Wolfsohn’s face a total of 2,997 times.

Over the following decade, the Salomon family navigated Germany’s increasingly tenuous political situation with mixed success. Albert, briefly detained and tortured following Kristallnacht, urged his daughter to leave the country. She joined her grandparents in southern France shortly thereafter and found her grandmother deeply depressed. When the elderly woman attempted to hang herself in September 1939, Salomon’s grandfather finally told her of the family’s long-concealed history of suicide. (Previously, she’d believed her mother died of influenza.)

A few months later, the artist’s grandmother jumped out of a third-story window, ending her life; soon after that, France’s collaborationist Vichy government detained Salomon and her grandfather in a concentration camp, subjecting the pair to horrific conditions but releasing them after several weeks.

Upon her return home, Salomon—driven to the point of breakdown by her internment and the revelation of her family’s history of mental health struggles—sought guidance from local doctor Georges Moridis. Her life, Moridis said, had reached a crossroads, leading her to debate “whether to take her own life or to undertake something eccentric and mad.” The doctor advised Salomon to channel her energy into a creative act: painting. Emboldened by this newfound purpose, the artist embarked on a spree of productivity.

“I will live for them all,” she wrote. “I became my mother, my grandmother. I learned to travel all their paths and became all of them. … I knew I had a mission, and no power on earth could stop me.”

In late 1942, Salomon rented a hotel room and transformed it into her studio. For several months, the hotel’s owner later recalled, she worked nonstop, “like one possessed.”

The end result, according to a blog post by Stanford University’s Cynthia Haven, was a masterful collection of 1,299 gouaches, 340 transparent text overlays and a total of 32,000 words. One painting finds the artist cuddling in bed with her mother; another shows a seemingly endless parade of Nazis celebrating Adolf Hitler’s appointment as Germany’s chancellor while swastikas swirl above their heads.

After completing her genre-bending creation, Salomon joined her grandfather in his Nice apartment. The pair’s reunion was contentious, to say the least: According to a 35-page confession tucked into the back of Life? or Theatre?, the artist murdered her abusive relative with a deadly “Veronal omelette” before returning to Villefranche, the Riviera commune where she’d lived upon first moving to France. (“Given that Salomon’s work so clearly blends fact with fiction,” Cath Pound writes for the New York Times, “we are unlikely to ever know if she actually did” kill him.) Here, she began a romantic relationship with Nagler, a Jewish Romanian refugee, and in June 1943, the couple married at the local town hall. Weeks later, the pregnant artist packaged up her life’s work and delivered it to Moridis.

In late September, Gestapo agents arrested the couple. Asked to provide her occupation, Salomon identified herself as “Charlotte Nagler, draftswoman.” On October 10, after a stop at the Drancy transit camp, she and her unborn child were killed at Auschwitz. Nagler died of exhaustion some three month after.

Life? or Theatre? spent the remainder of the war in Moridis’ safekeeping. Salomon’s father and stepmother, who had survived the Holocaust by hiding in Amsterdam, learned of the work’s existence after the war and organized the first show of their daughter’s art in 1961. In 1971, they donated the entire trove to the Jewish Historical Museum of Amsterdam.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/91/e1/91e1aa7c-8800-41b0-80d7-7c4ac44918e5/2565.jpg)

In the decades since Salomon’s story first came to light, her art has inspired theater productions, operas, films, exhibitions and novels. Still, Bentley observes for the New Yorker, Salomon has too often been grouped in the “ill-defined, unutterably sad category of ‘Holocaust Art.’” And while the events of World War II underlie the entirety of her oeuvre, Life? or Theatre? is centrally concerned with the artist herself, “her family, love, creativity, death.”

Salomon’s work pushed the boundaries of established artistic tradition, blending abstract and figurative painting with text in a storyboard-like format.

Dominik Czechowski, the London museum’s head of exhibitions, tells the Jewish Chronicle’s Anne Joseph that Life? or Theatre? was “basically … a prototype of a graphic novel.”

He adds, “She shows high originality in her work and she’s doing it on her own, with little formal training, at a time of heightened danger and anxiety, against the backdrop of oppressive, political events.”

As Pound points out for the Times, Life? or Theatre? combines memory and imagination, presenting flashbacks and split screens filled with a “dizzying array” of allusions to other art forms. Although Salomon referred to her creation as a Singspiel, or dialogue-heavy opera, Mirjam Knotter, a curator at the Jewish Historical Museum in Amsterdam, says it was “not meant to be played or performed.” Instead, Knotter tells Pound, the artist strove to “use her artistic mind to imagine how things were in the past.”

The final pages of Life? or Theatre? are decidedly optimistic. A painting of Salomon, presumably starting the first canvas of the project while enjoying a sunny seaside day, appears alongside a wall of text declaring that “With dream-awakened eyes she saw all the beauty around her, saw the sea, felt the sun, and knew: [S]he had to vanish for a while from the human plane and make every sacrifice in order to create her world anew out of depths.”

As Czechowski tells Joseph, “At the end, it’s almost like the beginning, as it shows Charlotte embarking on the process, painting the first image in the cycle.”

A question inscribed on the painted figure’s back further alludes to the work’s cyclical nature. Written in the same all-capitals scrawl seen throughout the narrative, the words have a familiar conceptual bent: “And from that came: Life or theater??? Life or theater?”

“Charlotte Salomon: Life? or Theatre?” is on view at the Jewish Museum London through March 1, 2020.

:focal(1299x1002:1300x1003)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e3/76/e376af81-c7a3-4a04-9f99-7eefe194f3e9/charlotte_salomon_-_jhm_4762_-kristallnacht_1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)