See Leonardo da Vinci’s Genius Yourself in These Newly Digitized Sketches

The Victoria and Albert Museum in London has made ultra high-resolution scans of two codices available online

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/41/97/41970501-f6cb-4211-aab4-e7245fd6c85d/screen_shot_2018-08-31_at_115059_am.png)

Leonardo da Vinci is best known for formal works of art like "The Last Supper" and the "Mona Lisa," but his true masterpiece may be the notebooks he left behind. Written in a mirror image, the notebooks reveal the brilliant, idiosyncratic mind of the original Renaissance man. Inside the volumes are ideas for new inventions including flying machines and weapons of war. Sketches for paintings, scientific experiments and doodles of all sorts of things, from human bodies to interesting hats, fill the pages. Of course, picking up and studying those precious books is impossible, but now da Vinci fans can get the next best thing. Gareth Harris at The Art Newspaper reports that the Victoria and Albert Museum in London has digitized two da Vinci notebooks, allowing readers to get up close to the manuscripts.

The digitized books come from a volume called the Codex Forester I, which is actually two notebooks that were bound together sometime after the artist’s death in 1519. One of the notebooks dates from his time in Milan and covers 1487 to 1490 while the other was created in 1505 in Florence.

The notebooks include notes and diagrams for projects including devices to move and raise water, which may have been used to create fountains or water clocks to entertain party guests. There are also designs for a perpetual motion machine, an idea da Vinci flirted with but eventually gave up.

“The notebooks remind us that Leonardo was as much an engineer as he was an artist. When he wrote in the early 1480s to Ludovico Sforza, then ruler of Milan, to offer him his services, he advertised himself as a military engineer, only briefly mentioning his artistic skills at the end of the list,” Catherine Yvard, special collections curator at the V&A’s National Art Library, tells Harris.

The books have been digitized using the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF). Not only are the scans of the books super-high resolution, allowing scholars to zoom in with incredible detail, the format is designed as an international standard. For instance, if a researcher wants to compare a page from a da Vinci notebook in the Codex Forester I to a page held by another museum, IIIF allows them to use one viewer to compare images, rather than switching between different digital viewers used by different libraries. The format will also allow researchers to create digital collections of documents that might be held by different institutions, for instance putting a manuscript back together whose pages were split up by collectors.

The technique not only allows many more people to see and examine the notebooks, it also preserves the precious documents. “If we want them to survive another five centuries and more, we need to make sure that we do not submit them to too much handling, while making their fascinating content accessible in different ways which will not harm them,” Yvard says.

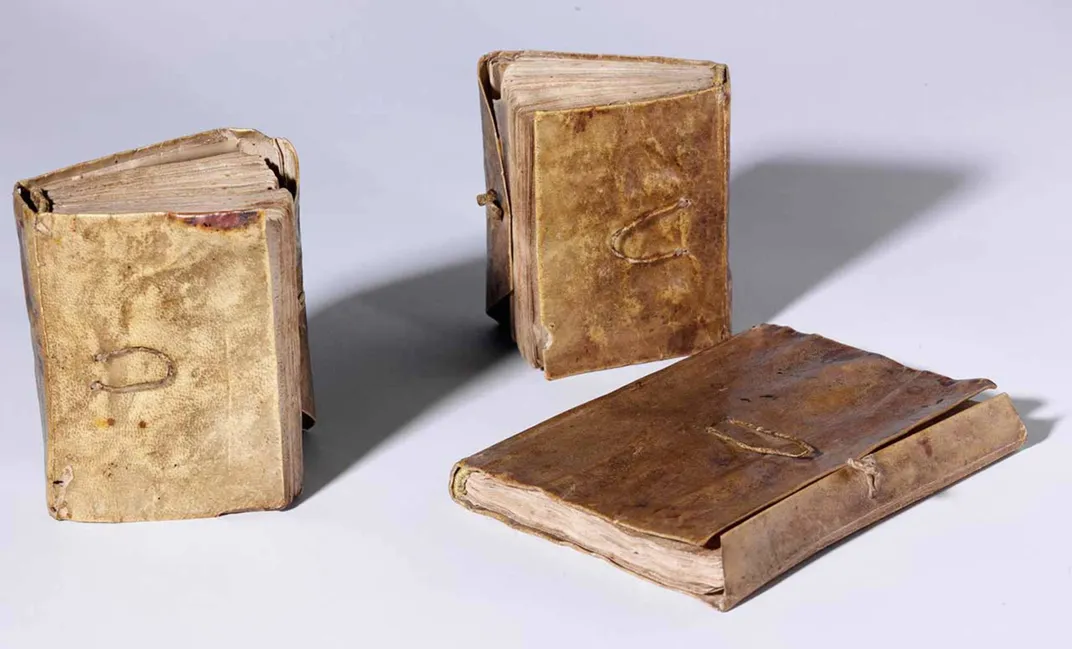

These are not the first da Vinci notebooks to go online. Last year, the British Library and Microsoft released 570 pages of the Codex Arundel, a group of notebooks dating between 1478 and 1518. It’s unlikely that da Vinci walked around Florence and Milan scribbling in a little notebook. Instead, it’s believed that he wrote on loose leaves of paper. After his death, the paper was bound into the notebooks. Later, the notebooks were bound into codices, though not much attention was paid to the chronology and earlier and later books were often bound together. As da Vinci’s fame grew, collectors around Europe began snatching up the notebooks, and now the volumes are spread throughout institutions across the continent, making digitizing efforts necessary to bring them all together.

In 2019, the V&A museum plans to release their other two collections of da Vinci notebooks, the Codex Forster II and III online to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the artist’s death.