Giant, Intact Egg of the Extinct Elephant Bird Found in Buffalo Museum

Fewer than 40 such eggs are held in public collections today

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7f/b4/7fb44516-11cb-4e56-a810-9daadb642fa1/bms_elephant_bird_egg_1.jpg)

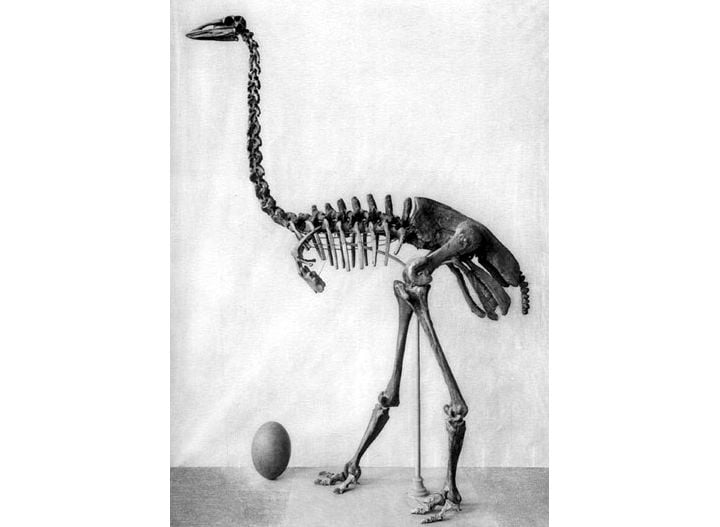

When humans first arrived on the island of Madagascar around 1500 years ago, they encountered an array of remarkable species that have since gone extinct: gorilla-sized lemurs, giant tortoises, tiny hippos and a huge, long-necked, flightless bird that lumbered through Madagascar’s forests and laid the largest eggs of any known vertebrate, including dinosaurs.

The eggs of the Aepyornis, also known as the elephant bird, were a highly valuable food source for Madagascar’s human settlers. With a volume roughly equal to that of 150 chicken eggs, a single elephant bird egg could feed multiple families. Humans pillaged the elephant birds’ nests, which likely played a role in driving the animals towards extinction. Today, few of the bird’s gargantuan eggs survive; fewer than 40 are known to exist in public institutions. So staff at the Buffalo Museum of Science were nothing short of thrilled when they found an intact, foot-long elephant bird egg hiding in the museum’s vast collections.

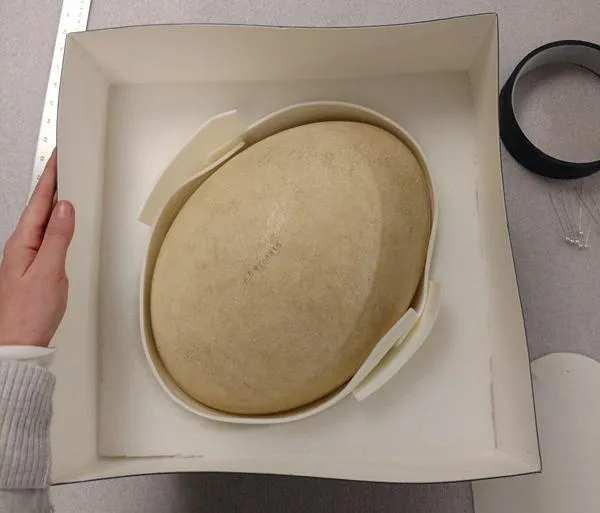

The Buffalo Museum of Science has been accruing its collection for well over a century and is currently in the process of updating its catalog, some of which still exists on cards and ledgers. While inputting catalog data into the museum’s computer system, Paige Langle, the collections manager of zoology, opened a cabinet that hadn’t been looked in for quite some time. Inside was an enormous, cream-colored egg. It measured 12 inches long, 28 inches in circumference and weighed more than three pounds. It was also labeled as a model.

Langle, however, immediately suspected that the egg was “too realistic to be a model,” she tells Smithsonian.com. “I tried to shrug it off, but the more closely I looked at the surface of the eggshell and felt the weight of the egg, the more I kept thinking this has to be real.”

She was right. Searching deeper in the collections, she found a replica of the elephant bird egg that was obviously the model in question. Museum staff then looked through the institution’s archives and found records indicating that the museum had purchased a sub-fossilized elephant bird egg from a London purveyor of taxidermy specimens in 1939. They also found a letter written by a curator at the time, who listed various objects that he wanted to acquire for an exhibit on birds. One of those objects was a an elephant bird egg.

“From what we could tell, he mailed this list to all kinds of dealers all over the world, several of them in London,” says Kathryn Leacock, the museum’s director of collections. “A couple of them wrote back and said, ‘Oh no, you're not going to get one of those. They're kind of expensive.’ Fortunately he didn't let that deter him.”

Museum staff sent the specimen to SUNY Buffalo State to be radiographed and authenticated. Conservation experts there not only confirmed that the egg was real, but were also able to determine that it had been fertilized. They could make out the yolk sac and, Leacock says, “white fragments” that may point to the beginnings of a developing bird.

The 40 or so elephant bird eggs that are owned by public institutions exist in varying states of completeness. The National Geographic Society in Washington, D.C., has an intact sub-fossilized elephant bird egg, and inside is an embryonic skeleton. But other institutions “just have fragments of the shell,” Leacock says. (It is hard to know how many elephant bird eggs are held in private collections; David Attenborough has one, and in 2013, another sold for $100,000 at a Christie’s auction in London.)

Leacock hopes that the newfound specimen at the Buffalo Science Museum will prove valuable to experts who are interested in the elephant bird. There were several species of this massive creature. The largest towered 10 feet high and weighed around 1,000 pounds. These magnificent creatures died out relatively quickly once humans came to Madagascar; the last sighting of an Aepyornis was in the 17th century.

It is not entirely clear why the birds went extinct, but anthropologist Kristina Guild Douglass said in an interview published on Yale’s website that “the answer is somewhere in the combination of climate change, changes in vegetation patterns, and human predation.”

“From my excavations,” she added, “human predation seems to be limited to egg-poaching.”

The elephant bird egg at the Buffalo Museum of Science has not been on display since the 1940s or 50s, Leacock says. The staff plans to feature the relic in an exhibition titled “Rethink Extinct,” which explores major episodes of extinction, from the age of the dinosaur to the present day.

“It's super, super cool to have this [egg] in Buffalo, and hope the community will be proud that we are one of a very, very few museums that have this as our cultural heritage,” Leacock says. “We're just very excited.”