Glitzy Beetles Use Their Sparkle for Camouflage

A new study suggests eye-catching iridescence isn’t just for standing out in a crowd—it can conceal, too

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/29/35/2935cbf1-f456-455b-ba73-6437c97036b1/10270100973_10ae50aaf3_o.jpg)

In nature, sometimes the best way to blend in is to stand out. This oddball strategy seems to work for the jewel beetle (Sternocera aequisignata), a super-sparkly insect famous for the dazzling, emerald-toned wing case that adorns its exterior. Like the florid feathers of a male peacock or the shimmer of a soap bubble, these structures are iridescent, shining with different hues depending on the angle they’re viewed from.

In most other creatures, such kaleidoscopic coloring can’t help but catch the eye, allowing animals to woo their mates or advertise their toxic taste. But according to a study published last week in Current Biology, jewel beetles might just turn this trope on its head, deploying their beguiling gleam for camouflage instead.

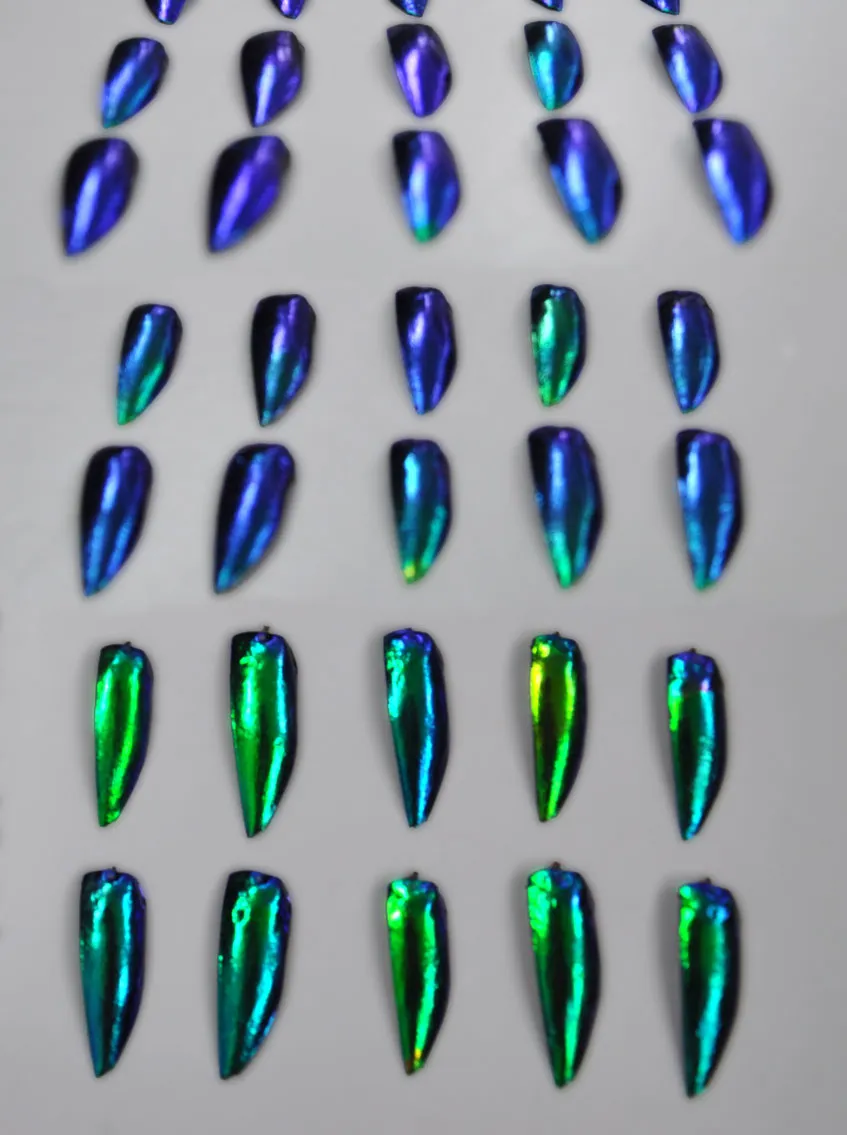

As Rodrigo Pérez Ortega reports for Science magazine, this counterintuitive theory was first proposed a century ago, but only recently tested in the wild. To see if the glitz and glam of jewel beetles might help them blend in against a forested backdrop, a team of researchers led by Karin Kjernsmo, an evolutionary and behavioral ecologist at the University of Bristol, placed 886 jewel beetle wing cases, each filled with larvae, atop leaves in a local nature reserve. Some wing cases were painted over with different colors of nail polish, stripping them of their sheen, while the rest were allowed to let their true colors shine. The team then tabulated which of the cases were most obvious to hungry birds, the beetles’ primary predator.

Over the course of two days, birds ended up attacking the iridescent decoys less than their painted counterparts, suggesting the more drab wing cases were actually worse at staying hidden. While the birds were able to nab 85 percent of the targets that had been painted purple or blue, they picked out less than 60 percent of the ones left au naturel. “It may not sound like much,” Kjernsmo tells Jonathan Lambert at Science News, “but just imagine what a difference this would make over evolutionary time.”

To rule out the possibility that the birds were simply shirking the shimmering beetles, perhaps as a way to avoid an unsavory or poisonous meal, the team repeated their experiment with a group of humans. People had an even tougher time homing in on the glittery bug parts, spotting less than a fifth of the iridescent wing cases they passed—less than a quarter of the proportion of the faux bugs painted purple or blue. Glossier leaves made the shiny wing cases blend in more easily.

Beetle expert Ainsley Seago, who manages insect collections for New South Wales Department of Primary Industries, praised the study in an interview with Mongabay’s Malavika Vyawahare. Seago, who was not involved in the research, says the findings are “a very useful and important step forward in determining the evolutionary origins of these ‘living jewels.’”

As Kjernsmo explains in a statement, the trick to the beetles’ disappearing act might involve dazzling their predators to an extreme. Their wing cases are so striking that they end up befuddling birds, who can’t pick out their prey from the rich background of a heavily textured forest.

Confirming that theory will take more research, and probably some creative thinking. As Seago points out, birds’ color vision differs from ours. But luckily, the researchers will likely have plenty of other animals to test their hypothesis on. From the flashiness of fish scales to the luster of butterfly wings, iridescence is everywhere. “We don’t for a minute imagine that the effect is something unique to jewel beetles,” Kjernsmo says in the statement. “Indeed, we'd be disappointed if it was.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)