Good News, Everybody! Someone Once Patented Plans For Keeping A Severed Head Alive

It was what’s called a “prophetic patent”—one that isn’t real yet

:focal(411x211:412x212)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d2/93/d2937dd7-5024-419a-9a2f-094091c9705d/head.jpg)

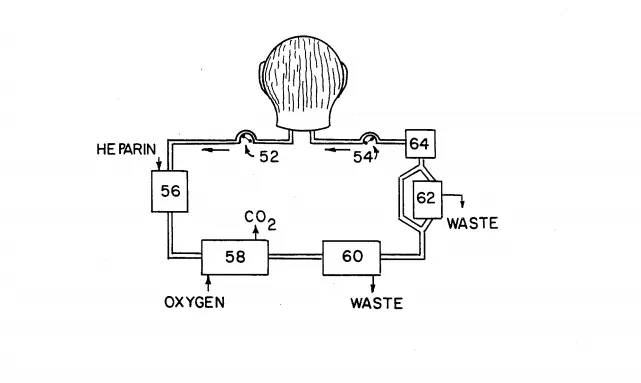

Thirty years ago today, Chet Fleming was issued a patent for “a device for perfusing an animal head.”

That device, described as a “cabinet,” used a series of tubes to accomplish what a body does for most heads that are not “discorped”—that is, removed from their bodies. In the patent application, Fleming describes a series of tubes that would circulate blood and nutrients through the head and take deoxygenated blood away, essentially performing the duties of a living thing's circulatory system. Fleming also suggested that the device might also be used for grimmer purposes.

“If desired, waste products and other metabolites may be removed from the blood, and nutrients, therapeutic or experimental drugs, anti-coagulants and other substances may be added to the blood,” the patent reads.

Although obviously designed for research purposes, the patent does acknowledge that “it is possible that after this invention has been thoroughly tested on research animals, it might also be used on humans suffering from various terminal illnesses.”

Fleming, a trained lawyer who had the reputation of being an eccentric, wasn’t exactly joking, but he was worried that somebody would start doing this research. The patent was a “prophetic patent”—that is, a patent for something which has never been built and may never be built. It was likely intended to prevent others from trying to keep severed heads alive using that technology.

In the realms of science fiction, severed heads are nothing new: from the 1942 classic Donovan’s Brain, to mid-century B-movie They Saved Hitler’s Brain and of course the television show Futurama—in which the severed head of Richard Nixon frequently teams up with the headless body of Spiro Agnew—living severed heads are an established science fiction trope.

But even now, keeping a head alive is a tough prospect, with or without Fleming's patent.

Sergio Canavero, an Italian surgeon who has been making news about his intent to do a head transplant for years, successfully transplanted a rat head onto another rat's body for the second time. Canavero keeps saying he intends to do a human head transplant by the end of 2017, writes Abigail Beall for Wired, but “the scientific community is deeply concerned,” she writes.

“Without a radical breakthrough in neurobiology, [head transplants] are not possible,” biologist Paul Zachary Myers told Wired. The big issue is nerve regeneration, she wrote, but there are a host of others, ranging from the ethical to the difficulty of finding a healthy donor body for the head to be placed on. As it stands, Beall writes, a head without a body wouldn’t survive for long.

Fleming did write a book about his patent. Reviewing it for the British Medical Journal, immunohematologist Terence Hamblin clearly believed Fleming—whose name, he notes, is a pseudonym—wasn't serious. “Mr. Fleming has taken out a prophetic patent on severed heads. Such a patent does not commit you to making the device, but it does prevent anyone else doing so, unless you license them," he wrote. "Mr. Fleming has done us a service in drawing our attention to this issue, and his ingenious method of stalling further development at present is rather fun.”

In his response, Fleming wrote, he was not actually trying to prevent anyone from keeping a head alive. The decision of whether to make such a device rests on “whether or not the advantages outweigh the disadvantages and dangers.”

“I have been contacted by half a dozen people who want to know how soon the operation will be available and how much it will cost,” he wrote. “Some are dying: others are paralyzed. Most said that if the mind remains clear and the head can still think, remember, see, hear and talk and if the operation leads to numbness rather than pain below the neck they would want it.”

For now, though, keeping a human head alive and sentient without a body remains the province of Futurama.