Grand Central Terminal Turns 100

The iconic New York building, which celebrates its 100th birthday this weekend, has a storied past

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130201023016south-side-statues-2.jpg)

Grand Central Terminal, the country’s most recognizable transportation hub, celebrates its 100th birthday today.

A legacy of the Vanderbilt family (whose adopted symbol, the acorn, sits atop the terminal’s trademark clock), Grand Central is more than just ticket booths, tracks and platforms, of which there are 44, making it the largest train station in the world based on platform number.

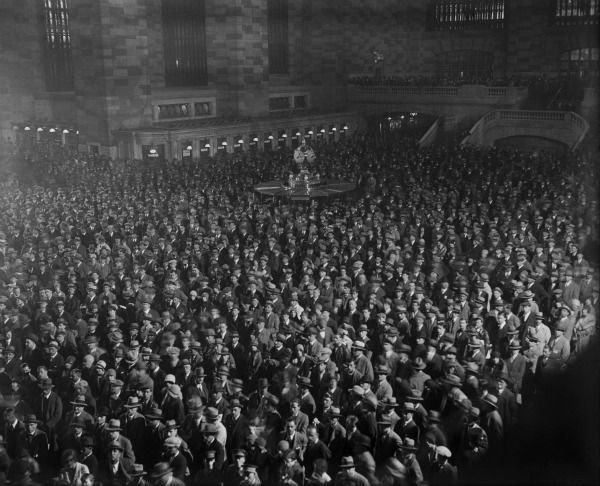

It’s a city within a city, housing 50 shops, 20 eateries, five restaurants, newsstands, a fresh food market and multiple passageways to maneuver around it all. Its train and subway systems serve nearly 200,000 commuters daily. In total, every day more than 700,000 people pass through the terminal, a Beaux-Arts style transportation hub that took ten years and $80 million to complete.

A quintessential New York spot, the 48-acre centenarian brings in approximately 21.6 million visitors each year. They come to see the cavernous main concourse and gaze up at the arched painted ceiling, to which as many as 50 painters contributed. The mural depicts constellations of the Mediterranean sky, but in reverse—an error that transportation officials explained away as an astronomical representation from God’s perspective.

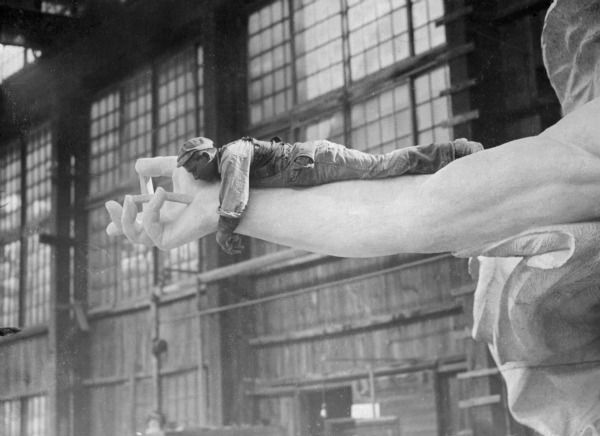

Visitors also come to survey the 50-foot statues on Grand Central’s south face depicting Mercury, Hercules and Minerva, the gods of, respectively, travelers, strength and commerce. And they come to see for themselves the famous four-faced, 13-foot-wide Tiffany glass and opal clocks.

Grand Central Terminal has a storied past, with several well-kept secrets that have since been exposed. A “whispering gallery” in the dining concourse near the Oyster Bar, a restaurant as old as the terminal itself, allows a quiet voice to travel from one end to the other, thanks to acoustics created by low ceramic arches. Past a door inside the information booth is a hidden spiral staircase, leading down to another information kiosk.

During World War II, German military intelligence learned of a once-secret basement known as M42, which contains converters used to supply electric currents to trains. Spies were sent to sabotage it, but the FBI arrested them before they could strike.

A train platform with a concealed entrance, number 61, was once used to transport President Franklin D. Roosevelt directly into the nearby Waldorf-Astoria hotel.

In 1957, a NASA rocket was displayed inside the terminal, a move meant to encourage support for the country’s space program as it raced against the Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik. A six-inch hole was carved into the ceiling to help support the missile, and it remains amidst the mural’s 2,500 stars.

In 1976, a group of Croatian nationalists planted a bomb in one of the terminal’s lockers, and the subsequent attempt to disarm the device killed a bomb squad specialist and injured 30 others.

The terminal’s interior has also been the backdrop to several Hollywood classics. In 1933, Bing Crosby received a star-studded sendoff at Track 27 in “Going Hollywood.” Twenty years later, Fred Astaire hopped off a train and danced up track 34 in a Technicolor musical number in “The Band Wagon.” The following year, Ingrid Bergman and Gregory Peck kissed inside the terminal before making their getaway in “Spellbound.” The 1959 action classic “North by Northwest” opens with a montage of New Yorkers bustling through the terminal, and Cary Grant later makes a nighttime escape through the main concourse.

Once dedicated to long-distance travel, Grand Central Terminal is now home to the Metro-North Railroad, the largest commuter railroad service in the United States. Three train hubs have stood at 42nd and Park Avenue since the 19th century. In 1871, Grand Central Depot consolidated several New York railroads into one station until it was partially demolished three decades later. What remained, dubbed Grand Central Station, doubled in height and received a new façade. Several years later, in 1913, a decade-long project transformed the hub into the iconic terminal anchoring midtown Manhattan today.

But the terminal’s fate hasn’t always been so secure. In the 1950s, multiple real estate developers proposed replacing it with towers, some 500 feet taller than the Empire State Building. By the late 1960s, the growing popularity of government-subsidized interstate highways and air travel had sapped the customer pool of railroads across the country. Grand Central wasn’t immune. Over time, the ceiling became obscured by tar and tobacco smoke residue, and commercial billboards blocked out natural light from streaming in.

By 1968, New York Central Railroad, which operated the terminal, was facing bankruptcy, and it merged with Pennsylvania Railroad to form Penn Central. The new company unveiled another tower proposal that year, but the plans drew significant opposition, most notably from former first lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. The terminal became a historic landmark in 1978, following a Supreme Court decision to protect the transportation hub, the first time the court had ruled on a matter of historic preservation.

In the 1990s, the terminal saw a massive, two-year, $196 million renewal project under Metro-North. The ceiling of the Main Concourse was restored, revealing the painted skyscape, the billboard were removed to let light in and the original baggage room was replaced with a mirror image of the west staircase, a feature that had been included in original blueprints but hadn’t come to fruition.

But Grand Central Terminal won’t remain unchanged for long. A two-level, eight-track tunnel is being excavated under Park Avenue to bring in Long Island Rail Road trains, and by 2019, thousands more will be coming and going, arriving and departing, through this historic landmark.

Many thanks to Sam Roberts’ indispensable, comprehensive history “Grand Central: How a Train Station Transformed America.”

More from Smithsonian.com:

What to Look for on the Train Ride From New York to Washington

Where the Buffalo No Longer Roamed

Trains of Tomorrow, After the War

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/marina-koren-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/marina-koren-240.jpg)