Gulf of Mexico “Dead Zone” May Grow to the Size of New Jersey This Year

Shrimp and fish may suffer as excess rain and nutrients produce one of the largest oxygen-poor zones to date

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/32/c3/32c341c0-dad1-4857-a41d-55abb755ba49/shrimp_catch_noaa_photo_library.jpg)

Shrimp lovers may want to start buying and freezing Gulf shrimp now.

New estimates released by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and U.S. Geological Survey predict that the Gulf of Mexico's “Dead Zone”—an area of low oxygen that negatively impacts its aquatic life like shrimp—will be larger than the state of New Jersey this summer. Predicted to span roughly 8,185 square miles, this will be the third largest it has been since measurements began 32 years ago.

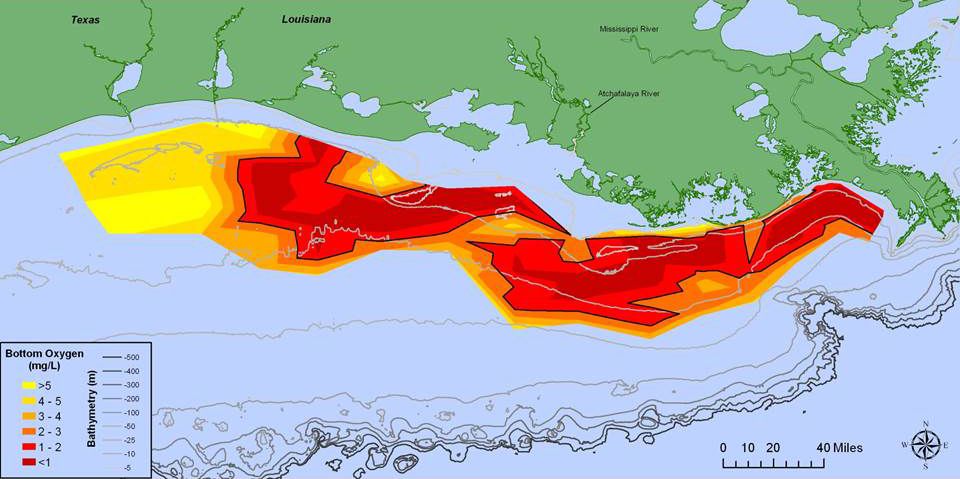

As Chelsea Harvey at The Washington Post reports, in scientific terms the Dead Zone is known as a hypoxic zone and is located off the coasts of Texas and Louisiana. Dead zones happen naturally in coastal waters all over the world, but are worsened by human activity. In the spring and summer, agricultural runoff flows into rivers in the Mississippi River watershed, eventually making its way into the Gulf.

Those nutrients, which include tons of nitrogen and phosphorous, promote massive algae blooms in the Gulf when the water warms up. The algae eventually dies and falls to the bottom, where it decomposes. This decomposition eats up the oxygen in the water, suffocating aquatic life.

According to NOAA, heavy rains in May increased average stream flows by 34 percent, which have carried higher than average nutrient loads into the Gulf. According to a USGS press release: "165,000 metric tons of nitrate—about 2,800 train cars of fertilizer—and 22,600 metric tons of phosphorus flowed down the Mississippi and Atchafalaya rivers into the Gulf of Mexico in May." The area from which these nutrients originate is wide: the watershed drains part or all of 31 states.

Multiple groups have independently analyzed the region, each predicting slightly different impacts of the runoff, reports Mark Schleifstein at The Times-Picayune. But all predictions suggest that the Dead Zone will be massive this year. The average dead zone is 5,309 square miles. The official NOAA estimate is that it will grow to cover an 8,185-square-mile zone. A team from University of Michigan and North Carolina State estimate a Connecticut-sized zone at 7,722 square miles. A team from Louisiana State University believes the zone may swell to 10,089 square miles, which would be a record.

In late July, when the dead zone is expected to reach its peak, a team aboard the state-owned research vessel Pelican will cruise the Gulf, measuring the actual size of the hypoxic area. Harvey reports that high winds or a tropical storm that churn up the waters could reduce the impact of the dead zone, but without those interventions researchers expect their estimates to stand.

Low oxygen levels stunt the growth of fish and shrimp, even resulting in documented spikes in the price of larger shrimp. “This is a real concrete, quantitative effect, which hits economies,” Alan Lewitus, a scientist with NOAA’s Center for Sponsored Coastal Ocean Research tells Harvey. “So it’s something to really recognize.”

States and researchers have tried to reduce the size of the Dead Zone since the 1990s, but they’ve had little success. Schleifstein reports that the Mississippi River/Gulf of Mexico Watershed Nutrient Task Force formed in 2001 had a goal of reducing the Dead Zone to 1,930 square miles by 2015. They missed that target by a longshot and now hope to reach that goal by 2035. But that’s still a stretch.

“There’s a federal-state task force to come up with recommendations state-by-state to reduce nutrients,” Nancy Rabalais, a professor of marine ecosystems at Louisiana State University tells Matt Smith at Seeker. “If you read the details of the forecast and the changes in flows over time, you can see there hasn’t been much of a change. Which means the few really concerted efforts to reduce nutrients have been overwhelmed by the usual way of big agribusiness in the watershed.”

But there is some room for hope. Lewitus tells Harvey that, despite this year’s bump upward, USGS data suggests that average nutrient loads are starting to decline—though that probably won’t make Shrimpfest any jollier this year.