The comic strip “Thimble Theater” had been running for a decade when cartoonist Elzie Segar introduced a new minor character on January 17, 1929. Two of the strip’s protagonists, Ham Gravy and Castor Oyl, find him at a seaport when they are looking for men to crew a ship. “Hey there! Are you a sailor?” Castor asks. The lanky man, who has a pipe in his mouth and an anchor tattooed on his oversized forearm, replies, “’Ja think I’m a cowboy?”

The snarky sailor man was none other than Popeye, and these were his first words. Nearly a century after his debut, he’ll soon be able to say (almost) anything you’d like him to. On January 1, 2025, Popeye—along with thousands of other copyrighted creations—will enter the public domain in the United States.

Every year, Jennifer Jenkins, director of Duke University School of Law’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain, publishes an exhaustive analysis of some of the most important works entering the public domain. This year, the list includes copyrighted titles from 1929 and sound recordings from 1924.

Works enter the public domain when their copyrights expire, typically 95 years after publication. At that point, they become free for anyone to adapt or build upon without permission—with a few caveats. Copyrights to audio recordings, meanwhile, expire 100 years after they were first put to wax.

Take Mickey and Minnie Mouse, who first appeared in animated shorts like “Steamboat Willie” in 1928. When those titles entered the public domain this past January, so did those early versions of the cartoon mice. Newer versions will follow with every passing year: The Mickey who wears his now-signature white gloves, which didn’t appear until 1929, is entering the public domain in 2025.

Similarly, the copyright is expiring only on the version of Popeye introduced in 1929. He looks much like the character today’s audiences recognize, with his bulging forearms, protruding chin and famous catchphrase (“I yam what I yam,” which he first uttered in November of that year). On the other hand, his memorable throaty grumble didn’t exist until 1933, when “Popeye the Sailor” became an animated short, and he didn’t start eating spinach to get him and his beloved Olive Oyl out of a jam until at least 1931.

Before he found spinach, Popeye got his superhuman strength from an even weirder source: a “whiffle hen” named Bernice, who grants luck to anyone who rubs her feathers. In a June 1929 strip, Popeye survives 16 bullet wounds by petting Bernice, who saves his life and sculpts his magic muscles. So even though the hen-petting Popeye is in the public domain, the spinach-eating hero won’t be fair game for a few years. (The same goes for his iconic theme song, which debuted in 1933.)

Trademark law further complicates matters. Unlike copyrights, trademarks don’t expire, and they’re designed to protect words or images linked to a specific brand. Hearst Holdings owns the trademark for the Popeye name and has filed applications to trademark certain graphical depictions of the sailor. “Trademark law is all about preventing consumer confusion, and not about getting in the way of creativity,” writes Jenkins on Duke’s website. “You can still legally put the 1929 Popeye character in a new creative work in a way that does not mislead purchasers into thinking they are getting a Hearst-branded product.”

What should 21st-century storytellers do with characters like Popeye? In recent years, filmmakers have developed a penchant for creating poorly reviewed live-action horror movies featuring beloved children’s cartoons, like Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey (2023) and The Mouse Trap (2024). Popeye the Slayer Man will be released in 2025. So it goes.

As Jenkins points out, many of the celebrated classics entering the public domain this year were themselves built atop other public domain works. Disney featured more than a dozen copyright-free songs in its 1929 Mickey cartoons. William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, which enters public domain on January 1, gets its name from Shakespeare’s Macbeth: “[Life] is a tale / Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, / Signifying nothing.” Faulkner, Jenkins writes, is an “author of a timeless work that took from the public domain and now gives back to it.”

Here are just a few of the renowned books, movies, musical compositions, sound recordings and artworks entering the public domain in 2025.

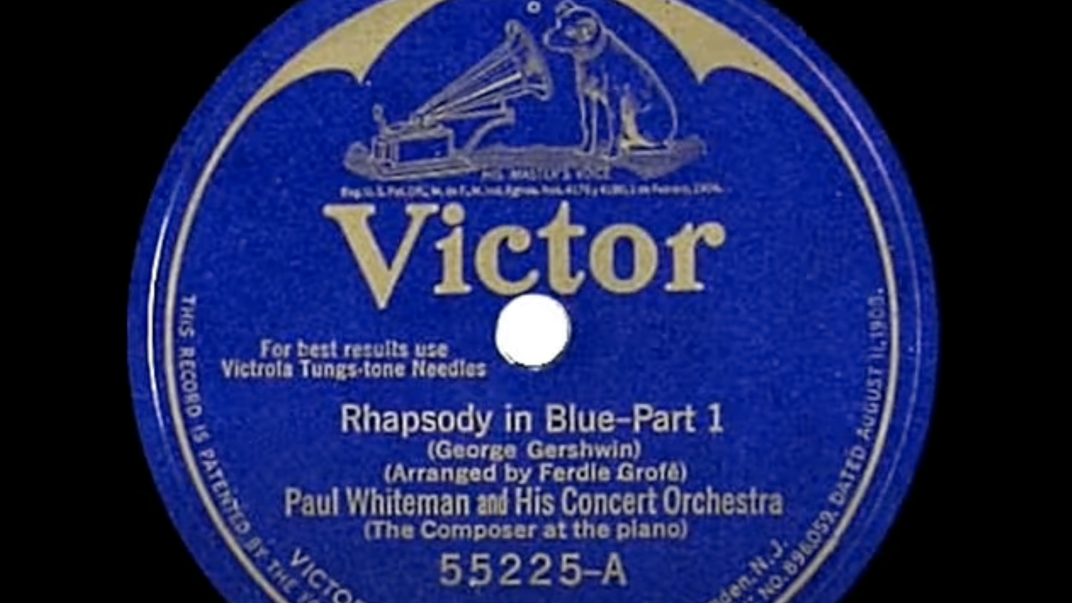

First recordings of Rhapsody in Blue by George Gershwin

Gershwin revolutionized American music and ushered in the Jazz Age, but the 25-year-old composer wrote his groundbreaking rhapsody rather hastily. He had been asked to compose a piece for a concert called “An Experiment in Modern Music” at New York’s Aeolian Concert Hall in early 1924. Accounts differ regarding what happened next: Some say he agreed and then forgot, while others insist he was forced to agree after a premature report that he was “at work on a jazz concerto” appeared in the New York Tribune.

In any case, Gershwin created a composition that masterfully melded elements of jazz and classical music in a matter of weeks, and it’s since been featured in everything from comedies to Disney’s Fantasia 2000 to commercials. Today, many listeners can instantly recognize Rhapsody in Blue from its opening clarinet solo.

The work itself entered the public domain five years ago, but the nearly nine-minute-long recording released later in 1924, featuring Gershwin himself as the piano soloist, is now available for public re-use. “First-time listeners are struck by a bolt of optimism,” wrote the New York Times upon its 100th anniversary earlier this year. “A new day is here!”

Boléro by Maurice Ravel

Ravel, a French composer whose career blossomed at the turn of the 20th century yet spanned decades, is undoubtedly best known for a strange, hypnotic piece he wrote in his 50s. Boléro features a minimalist rhythm played on a snare drum—and repeated throughout the 15-minute-long piece a total of 169 times. On top of the rhythm, different sections of the orchestra take turns playing two themes over and over again. Some find the repetition boring, but as a critic wrote in the Spectator in 2022, “Only boring people are bored by Ravel’s Boléro.”

The perseverative composition was published in 1929, around the time that Ravel started experiencing symptoms of a neurological disorder. As it happens, perseveration is a term used to describe a tendency to repeat words and actions often observed in conditions like Alzheimer’s. In recent decades, scientists have started to wonder whether Ravel composed Boléro not in spite of his disease, but because of it.

“Singin’ in the Rain”

More than two decades before the eponymous musical, the song “Singin’ in the Rain” was first heard in the 1929 film The Hollywood Revue. One of the earliest sound pictures released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, it featured the studio’s biggest stars in a variety of short acts. One of those acts was “Singin’ in the Rain,” which opens with Cliff Edwards (who would later voice Jiminy Cricket in 1940’s Pinocchio) strumming a ukulele as water pours down on stage. After about a minute, Edwards retires the instrument, and the production becomes a big dance number—not too dissimilar from the rendition most viewers are familiar with today. The song returns in the finale, when the entire cast sings a jaunty reprise. The movie itself, naturally, also enters the public domain in 2025, which is why the song does as well.

It’s a peculiarity of copyright law, as explained by the Duke center, that the rule for sound recordings, with their 100-year copyright term, specifically excludes “sounds accompanying motion pictures.”

A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8b/00/8b006ecc-f67f-4ad2-a1a1-2955b77e1d73/gettyimages-1380505455.jpg)

Woolf’s seminal 1929 essay is based on lectures she gave at Girton College and Newnham College, the first two women’s colleges established at the University of Cambridge. When she was asked to speak, she realized she would be unable to fulfill “the first duty of a lecturer, to hand you after an hour’s discourse a nugget of pure truth to wrap up between the pages of your notebooks and keep on the mantelpiece forever.” Instead, all she could offer were her thoughts on one small matter: “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.”

As Woolf points out, women had long been barred from pursuing an education or engaging in intellectual life. If William Shakespeare had had a sister who was just “as adventurous, as imaginative, as agog to see the world” as the Bard, Woolf argues, said sister would have had “no chance” of attending school and learning basic grammar, “let alone of reading Horace and Virgil,” writes Woolf. Perhaps such a woman would have been pressured into an early marriage—and would have ultimately killed herself, as Woolf herself would do in 1941.

But on a longer time scale, Woolf was hopeful: In “another century or so,” if women have “500 [British pounds] a year each of us and rooms of our own” and “the habit of freedom and the courage to write exactly what we think,” then perhaps “the opportunity will come and the dead poet who was Shakespeare’s sister will put on the body which she has so often laid down,” writes Woolf in her conclusion. “Drawing her life from the lives of the unknown who were her forerunners, as her brother did before her, she will be born.”

A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0c/50/0c5087c0-ae59-4b59-9023-7bee6a3af0ca/gettyimages-640468549.jpg)

Sometimes lauded as the best American novel produced about World War I, Hemingway’s first best seller follows an American ambulance driver in Italy who is wounded by a mortar shell. While recovering in a Milan hospital, he falls in love with a nurse.

Much of the novel is taken from Hemingway’s experience in the war. Like his protagonist, he drove an ambulance in Italy, and he was badly injured in the summer of 1918. During his hospital stay, a 19-year-old Hemingway fell in love with Agnes von Kurowsky, a 26-year-old nurse. About a decade later, he drew from the love affair to write his novel, using his famously sparse style to convey a sense of muted disillusionment.

The Broadway Melody

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/42/21/422104c5-34ad-4f46-8ab4-20467a19dbe5/gettyimages-3311087.jpg)

Two years ago, Wings, the first film to win an Academy Award for best picture, entered the public domain. This year, history’s second-ever Oscar winner will follow: The Broadway Melody, which is also the first sound film (and the first musical film) to win the honor. The picture follows two sisters who take their vaudeville act to Broadway—and become entangled in a love triangle along the way. MGM billed the film as an “all talking, all singing, all dancing” production, though it also released a silent version for theaters that lacked the equipment to show sound films. The New York Times called it a “talking picture teeming with the vernacular of the bright lights and backstage argot” but gave it a mixed review: “Although the audible devices worked exceedingly well in most instances, it is questionable whether it would not have been wiser to leave some of the voices to the imagination, or, at least to have refrained from having a pretty girl volleying slang at her colleagues.”

The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/03/e8/03e8eb8d-ba8f-4672-a519-62addb2c3f07/gettyimages-515388328.jpg)

Famous for its difficulty, Faulkner’s fourth novel chronicles the demise of the Compsons, an aristocratic family in Mississippi, from four perspectives. The Sound and the Fury is known for its stream-of-consciousness narration and nonlinear structure, and it’s celebrated as a pivotal Modernist text. In an interview several decades after its publication, Faulkner said that he initially tried to tell the story from the perspective of Benjy Compson, a man with an unnamed intellectual disability that muddles his sense of time, “since I felt that it would be more effective as told by someone capable only of knowing what happened, but not why. I saw that I had not told the story that time. I tried to tell it again, the same story through the eyes of another brother.” The published novel includes sections told by all three Compson sons and a third-person omniscient narrator.

Tintin

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b1/da/b1dad24c-a19b-417f-849d-31a8a8be219f/gettyimages-1442470306.jpg)

The Belgian newspaper Le Petit Vingtième began running a cartoon about a plucky young journalist named Tintin and his dog, Snowy (Milou, in the original French), in 1929. In the ensuing decades, Hergé (the pen name of the celebrated Belgian cartoonist Georges Rémi) sent the boy reporter looking for adventure—and exposing scandals—around the globe. The cartoons have been translated into dozens of languages and adapted many times, including in the 2011 film The Adventures of Tintin, directed by Steven Spielberg, who acquired rights to the story after Hergé’s death in 1983. In the European Union, where copyright law protects works until 70 years after the creator’s death, Tintin won’t enter the public domain until the 2050s. But in the U.S., anyone can send Tintin on his next adventure for free.

New Mickey Mouse animations

Mickey and Minnie Mouse debuted in a series of 1928 Disney shorts, including “Steamboat Willie,” one of the first cartoons with synchronized sound. When the characters first entered the public domain in January 2024—a big day for avid copyright watchers—the public only gained access to the versions of the characters featured in the 1928 productions. Come 2025, 12 animations released in 1929 will follow. These include “The Karnival Kid,” in which Mickey speaks his first words (“hot dogs!”), and “The Opry House,” which shows Mickey wearing white gloves for the first time. (Whether Mickey’s red shorts are protected by copyright is debatable, but even if they are, they’ll enter the public domain in a few years, along with the first colorized Mickey cartoons from 1935.)

Popeye

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/88/ab/88ab0d9d-4be2-4c77-96ba-42db49c2ee01/gettyimages-1883363.jpg)

When the sailor man appeared in “Thimble Theater” in 1929, Segar thought he would be a minor character who exited the strip after a few months. But audiences couldn’t get enough of Popeye, whose syndicated comic strip is still running to this day. “Popeye is much more than a goofy comic character to me,” said Segar in the book Wild Minds: The Artists and Rivalries That Inspired the Golden Age of Animation. “He represents all of my emotions, and he is an outlet for them. … To me, Popeye is really a serious person, and when a serious person does something funny—it’s really funny.”

:focal(800x602:801x603)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/89/ed/89ed5f45-c9be-422a-8388-b2b158b32245/publicdomain2025.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ellen_wexler.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ellen_wexler.png)