Here’s Where Species Loss From Climate Change Will Probably Be Most Extreme

Impacts to species around the world due to climate change are uncertain, but here’s a data-backed idea of how things will play out

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1a/e2/1ae2e89a-d76b-4ca6-993f-ca1a1e0cb3a5/french_woodmouse.jpg)

Species are already beginning to respond to climate change, with cherry blossoms blooming earlier in Japan, for example, and butterflies in the U.K. spreading north as the planet warms up. But not all plants and animals can simply move or adjust to changing conditions, and many, for whom climate change will likely be too drastic and arrive too quickly, will go extinct.

But how different the planet's biodiversity will be depends on a number of factors, including the degree of warming, the species in question and the landscape. A new paper in Nature attempts to estimate the degree of widespread change in store for the Earth's creatures.

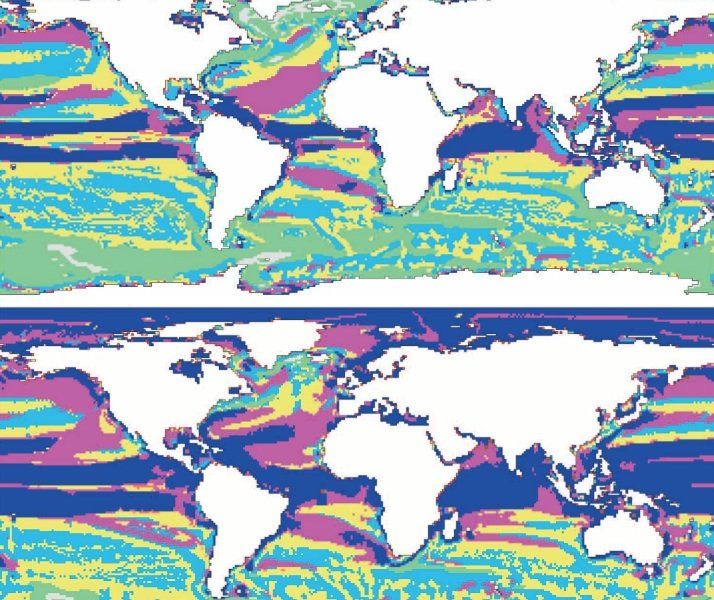

The study's authors used 50 years of climate data from the land and sea surface, then projected temperatures onto future global maps. They adusted the models to fit two scenarios, one that assumes we taper off our greenhouse gas emissions, stabilizing them by 2100, and another that assumes we continue to emit greenhouse gases under a business-as-usual scenario.

These calculations found "climate sinks"—areas where a coastline or body of water blocks species' movement. A species of mouse moving north from France, for example, might run into the English Channel, halting their escape and ultimately dooming those animals. “There are a number of those sinks around the world where movement is blocked by a coastline, like in the northern Adriatic Sea or the northern Gulf of Mexico, and there’s no way out because it’s warmer everywhere behind,” co-author Carrie Kappel explains in The Current.

Sometimes these sinks can form on land, too, when a sudden change in temperature pops up. An animal running south from Australia's northern coastline will not find the country's already extremely harsh interior any more inviting, for example.

Here's how this looks in this oceans: At top, greenhouse gas emissions stabilize by 2100; in the bottom, emissions continue to increase. The darker areas are places where species loss will be most pronounced; the light green areas will remain relatively stable.

The authors hope the maps can help anticipate scenarios in which conservationists might be able to help species in trouble, such as with assisted migrations.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)