‘Hot Lincoln’ Stands in Long Line of Attractive Presidential Sculpture

Before hot Lincoln, there was ripped Washington, nude Napoleon and muscular ancient Greek sculptures

:focal(1887x647:1888x648)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/07/79/0779ee6a-baf1-4d4c-8166-54921b6e0ce4/4715184094_a75ba6404c_o.png)

It’s a generally accepted fact that Abraham Lincoln, top-hat-wearing unifier, wasn’t a dream boat. Our tallest president to this day—he towered at 6 feet 4 inches—was gangly, with a craggy face and, in the words of Walt Whitman, a “doughnut complexion.” One journalist described him both as “the homeliest man I ever saw” and “a huge skeleton in clothes.” But did we get it wrong? Was the 16th president, actually, Hollywood-star hot? That’s the version of Lincoln peddled in a 1941 statue at a federal courthouse in Los Angeles. The 8-foot-tall statue recently went viral, and it’s quite… something. The limestone Lincoln appears shirtless and shredded, tugging at the waistband of his zipper-less trousers like a presidential Calvin Klein ad.

“Hot Lincoln” (née The Young Lincoln) was the product of a 1939 public art contest won by James Lee Hansen, an art student in his twenties who hailed from Fresno, California. When asked at the sculpture’s reveal party about the historically anachronistic choice to make the president a shirtless hunk, Hansen replied, “From a sculpturing standpoint, it’s better to show the body without any clothes. That’s why I left ’em off.”

Whether Hansen realized it or not, his Young Lincoln statue stands on a muscular tradition of amping up the sex appeal of leaders that goes back at least to the Greeks, who used buff bodies to communicate their subjects’ physical and moral fortitude. The concept was grounded in the scientifically debunked concept of physiognomy. Mount Holyoke professor Christopher Rivers explains in his book Face Value that physiognomy, which was espoused by ancient Mesopotamians and then more formally set out by the Greeks, is the idea that someone’s outward appearance reflects that person’s inner characteristics. The complementary Greek concept of kalokagathia, which conflated athletic beauty with an equally appealing soul, also supported this concept.

The idea that the outer appearance communicates something about someone’s inner self threads itself throughout art history. Historian Susan Doran points out that Elizabeth I’s government made a concerted effort to rid her kingdom of unauthorized portraits so that her public image evinced a young, virginal ruler long after she grew out of that image. The savvy monarch knew that representing herself as a youthful, virginal beauty positioned her in line with divine figures, like the Virgin Mary or the Roman goddess Diana.

It was during the last Tudor queen’s long reign that physiognomy began to gather more steam, advanced by the 1585 publication of a wildly influential treatise by Italian scholar Giambattista della Porta, which paired images of humans with the animals their features and mental traits purportedly corresponded to.

Physiognomy was very much alive and well in America when the first presidential images were recorded. Painter Gilbert Stuart, for instance, famously altered portraits of George Washington that he worried made the first leader of the United States seem “sensitive looking.”

Lincoln aside, Washington is the other president who frequently receives the stone hottie treatment. Horatio Greenough’s 1841 Zeus-inspired statue of Washington, commissioned by Congress for the first president’s 100th birthday, appears shirtless, wearing a toga and holding out a sword. The sight of presidential pecs so scandalized critics during the unveil that the statue was moved from the Capitol rotunda to the Capitol grounds after only two years; it’s now on display in the National Museum of American History. Another Washington notable comes thanks to Italian sculptor Canova. After Thomas Jefferson’s recommended him to create a Washington sculpture for the North Carolina capitol, Canova famously made a preliminary plaster model of the president in the nude, though his final statue was clothed—an act of restraint, since he did portray Napoleon as the naked war god Mars.

Imagining a political leader as a god was about more than just classical Greek aesthetics. As University of Georgia scholars Eugene Miller and Barry Schwartz write in an essay about American political portraits. presidential images often serve the same function as religious icons do: They inspire viewers to loftier moral heights.

That brings us back to Honest Abe—specifically, three mid-20th-century statues of him. For those looking to imitate Judeo-Christian religious imagery in the presidential form in the early 20th century, they’d have been seeing a lot of sinewy Nazareth types. The turn-of-the-century “muscular Christianity” movement, which started in England and spread to the U.S., focused on depicting the religion in a brawny light, according to research by Timothy August, an assistant professor of comparative literature at Stony Brook University. Muscular Christianity arose out of dark anxieties about societal change, including women’s growing role in public life and the influx of immigrants who inhabited the self-made, working-man mold that had traditionally been the American masculine ideal. (The early Eugenics movement also intersects with the movement.)

That meant to communicate a morally exemplary Lincoln meant capturing a physically fit Lincoln. While the Young Lincoln in Los Angeles might be the most scantily-clad of the trio, another work also titled Young Lincoln (this one bronze) deserves an honorable mention for airbrushing the president’s looks.

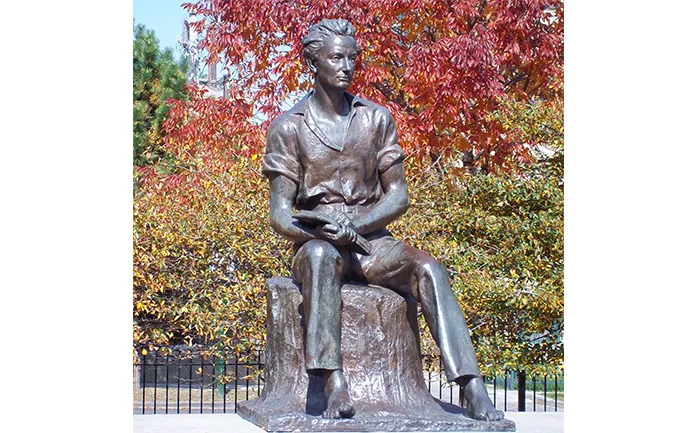

Artist Charles Keck crafted the statue in 1945, just a few years after the Hansen completed his version of The Young Lincoln. Keck’s statue, now on view in Edgewater, Illinois, features the president barefoot and seated on a tree stump, with his sleeves rolled up on his button-up shirt that artfully exposes a sliver of chest. The statue’s hair is also tousled to a degree most commonly associated with boy bands.

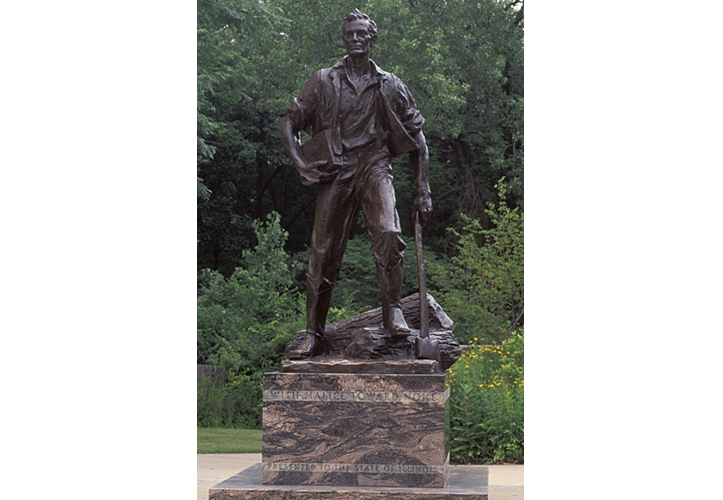

Then there’s the 1954 larger-than-life heroic bronze Abraham Lincoln for New Salem statue made by prolific Lincoln sculptor Avard Fairbanks. In the words of Fairbanks' son Eugene, the work depicts Lincoln “a vigorous young man about to set aside an ax while holding a large law book." In this case, “vigorous” can be translated to mean swashbuckling and 28. In the statue, Lincoln's coat is even blowing open in the wind, supermodel style.

Which is all to say that Baebraham Lincoln, the apple of social media’s eye, shirtless in the Los Angeles courthouse, may very well be following an artistic tradition, born out of a pseudoscience, to make our political leaders’ looks match their moral virtue. (Alarmingly, the electoral benefits of chiseling some cheekbones may be backed up by research; in 2007, a team from Princeton and Columbia Universities found they could predict gubernatorial elections based on candidates’ faces alone.)

Or, you never know, maybe it’s as simple as what Hansen suggested: the president just looked better sans shirt and jacked.