How a 1604 Supernova Presented a Challenge to Astronomers

The supernova provided proof to Galileo, Kepler and others that the heavens were not fixed–although they were wrong about what caused the bright star

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c7/e9/c7e98451-0bb9-4560-9398-6b5da4808e22/keplers_supernova.jpg)

More than 400 years ago, a bright new star appeared in the sky. Its appearance helped a groundbreaking generation of astronomers puzzle out new things about how the universe worked.

Supernova 1604 has long been referred to as “Kepler’s Supernova,” after astronomer Johannes Kepler, who was one of the first to observe it. “Brighter than all other stars and planets at its peak, it was observed by German astronomer Johannes Kepler, who thought he was looking at a new star,” writes Megan Gannon for Space.com. “Centuries later, scientists determined that what Kepler saw was actually an exploding star.” This supernova posed a challenge to seventeenth-century astronomers, who found themselves observing something that contradicted all conventional wisdom about the cosmos.

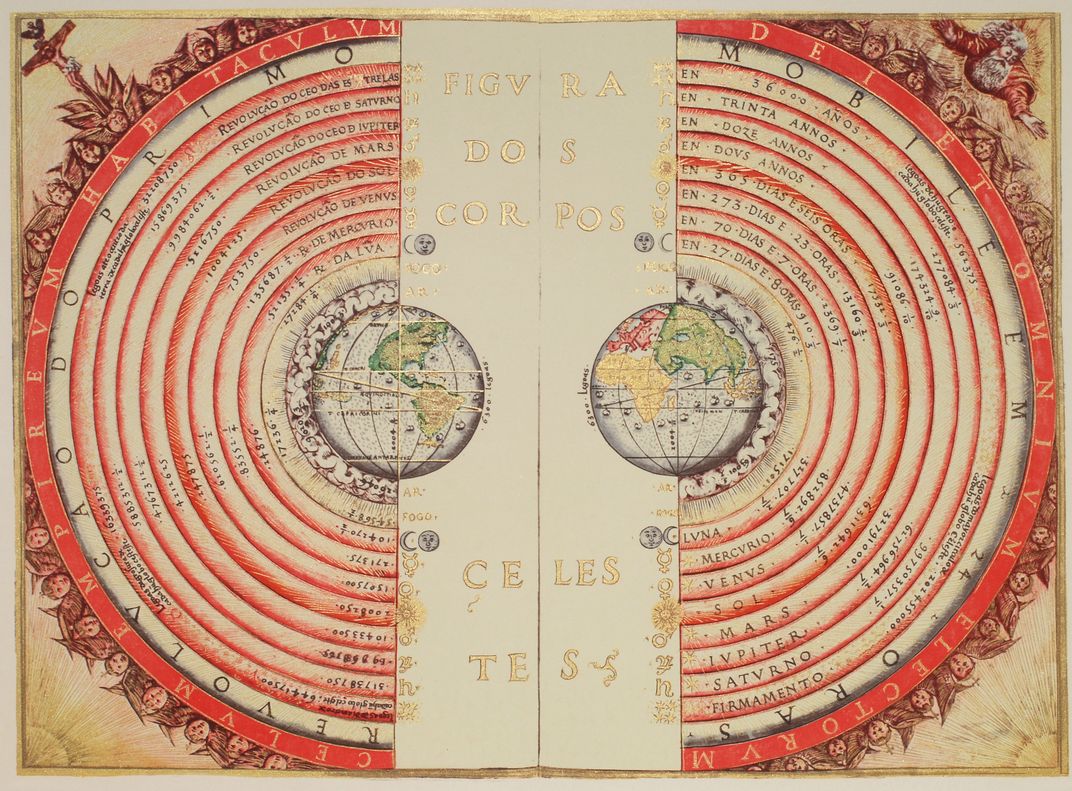

The conventional view of the cosmos placed the Earth at the center of our solar system, and in fact the whole universe. This Earth-centric worldview came originally from Aristotle and Ptolemy, two ancient philosophers. Aristotle’s On the Heavens said that the Earth was the realm of imperfect things and was changeable, while things far away from the Earth were perfect and didn’t change. From these principles, he developed a complicated model that could (sort of) accurately predict the movement of planets in the Solar System and other observable phenomena.

Early in the 1500s, Nicolas Copernicus had postulated an alternative to Aristotle’s version of the cosmos that placed the sun at the center of the solar system. This theory had made the rounds in Europe, but there was no proof that Aristotle was wrong until a series of celestial events culminating in the 1604 supernova provided it.

The 1604 supernova was the last one recorded in the Milky Way to date, but in the preceding century, astronomers had observed another of these rare events as well as a smaller nova. Aristotle’s perspective didn’t account for these events.

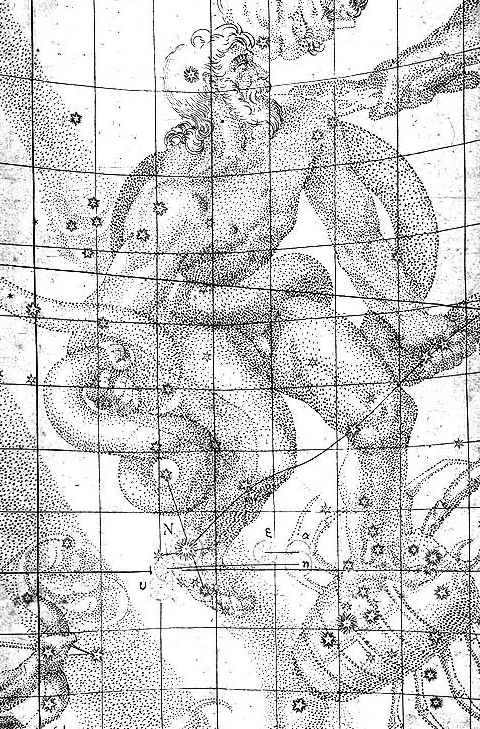

Astronomer Tycho Brahe had observed a 1572 supernova that was visible until 1574. “Other European observers claimed to have noticed it as early as the preceding August, but Tycho’s precise measurements showed that it was not some relatively nearby phenomenon, such as a comet, but at the distance of the stars, and that therefore real changes could occur among them,” writes Encyclopedia Britannica.

Kepler’s supernova was visible to the naked eye in daytime. It wasn’t a totally unheard-of phenomena in astronomical circles. And it worried people. “The immutable heavens stood in contrast to the ever-changing realm of Earth. So, what did it mean, did it portend some great event?” writes Nick Kollerstrom for Astronomy Now. Astronomers like Kepler and Galileo Galilei hastened to understand it. “Was it God’s angry eye, an omen of disaster?”

At this point, Galileo was a lecturer in mathematics and Kepler was the Imperial Mathematician in Germany, a position that Brahe previously held. Their positions required that both of them make attempts to figure out what the supernova was and answer the question of what it represented.

Although Galileo lectured on the star, in 1604 he was unwilling to commit publicly to it being farther away from the Earth than comets were believed to be. However, this supernova and the others pop up in his correspondence with other astronomers, writes Kollerstrom. Because the so-called new star didn’t show any detectable movement in the sky, the way the moon does, there was mathematically calculable evidence that it had to be farther away than the moon—that is, in the part of the sky that was believed to be fixed.

Kepler also wrote on the new star, and he was more confident in concluding it was ”located within the Milky Way and a few degrees due North of the ecliptic,” outside the range of close-to-earth space where it was believed that things could change.

These observations, which came at a turning point in the history of understanding of the cosmos, provided the groundwork for further theorizing that eventually led to the understanding that the Earth was not the center of the universe. However, the astronomers who believed they were seeing the birth of a new star were wrong: they were seeing brilliant celestial deaths happening close to home, the kind that modern astronomers can only wish to observe.