Two Artists in Search of Missing History

A new exhibition makes a powerful statement about the oversights of American history and America’s art history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d2/30/d2309d90-ed71-44ba-abe0-e2fadbc70125/exhpn154.jpg)

Sometimes what’s absent from a museum says more about history than what’s included. Two contemporary artists—Titus Kaphar, who is African-American, and Ken Gonzales-Day, who is Mexican-American—have spent their careers addressing this issue.

In the National Portrait Gallery’s newest exhibition, “Unseen: Our Past in a New Light,” the two artists take contrasting approaches—and work in two different mediums—to tell the stories of the missing and overlooked. The museum’s director Kim Sajet says Unseen hopefully will act as a town square. “It seeks to encourage discussion about history, how we remember, and how portraits can be a way to understand ourselves,” she says.

For centuries, portraiture—in America and elsewhere—has been devoted to the exposition of the lives of the rich, the famous, the royal, the historical, the heroic. But what about those Americans who didn’t get to have their portraits painted—because they were not white, or not a landowner, or a member of a wealthy family? What does art—and art history—say about them?

Unseen challenges portraiture’s tradition, says Asma Naeem, the Portrait Gallery’s curator of prints, drawing and media arts and a co-curator of the new exhibition. “Whose picture is shown on our walls? Who has been erased from history? Who hasn’t been shown?” The exclusions “can lead to different interpretations of history,” says Naeem.

Titus Kaphar’s approach is to amend history.

The 17 paintings and one sculpture in Unseen are the largest exhibition of the Yale-trained and New Haven, Connecticut-based artist’s works to date. One painting—Shred of Truth—has not previously been shown. He makes painstaking copies of historical paintings and then alters them—with a whitewash, with tar, by shredding or binding the canvas, by making paintings behind the paintings, to expose hidden truths. These are not one-dimensional, flat works.

Is Kaphar’s work the truth? Or is it his truth?

“All depiction is fiction—it’s only a question of degree,” is his response. “Every time we attempt to reproduce, to re-present, to represent an image, we change it slightly,” he says. The 41-year-old artist could be called an activist—though it is a label that he does not apply to himself.

With previous experience in construction, Kaphar “can rip something down to the studs, and then show us the beams, show us the framework, and make us understand deeper issues,” says Naeem, the curator.

White paint, applied sloppily with a broad brush—as if someone had vandalized the painting—is used to take characters out of a scene. In “The Fight for Remembrance,” a portrait of a black Civil War soldier, the man is still somewhat visible behind the slashing white strokes. Kaphar used the same technique to create a 2014 painting of Ferguson, Missouri protesters—used as Time magazine’s cover honoring the Black Lives Matter movement.

To call the technique a “whitewash” is oversimplifying, Kaphar says. The paint “doesn’t in fact erase everything that’s there,” he says. “It implies that there is erasure at the beginning, that erasure is taking place, but the narrative of the individual hasn’t been fully lost.”

In fact, the artist mixes varying amounts of linseed oil into the white paint, which, over time, makes it more transparent, allowing the character to become fully whole again.

Kaphar clearly finds purpose in questioning the dictums of history. His subjects almost always are chosen in reaction to a personal experience, he says.

The 2014 Columbus Day Painting—which greets "Unseen" visitors in the first gallery—was inspired by his young son’s conflicted and confusing study of the putative discoverer of America. Kaphar recreated the Landing of Columbus, originally painted by American neoclassicist John Vanderlyn. Congress commissioned the painting in 1836 and it was installed in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol in 1847. The painting still hangs there—enshrined as historical truth.

It depicts Columbus’ landing in the New World in 1492, showing the explorer and his crew triumphantly raising their European nations’ banners on the shore of what is now San Salvador island in the Bahamas. In the background, small, barely visible brown people warily watch from behind palm trees.

In Kaphar’s version, the Italian and his shipmates are literally bound up with cloth that’s been shoved into their body forms on the canvas. They’re like mummies—preserved for eternity, rendered inert and silent, or perhaps silenced. Meanwhile, the West Indies natives are still there, asking the viewer to consider their presence.

Kaphar says he was moved to recreate the 1835 portrait of Andrew Jackson by Ralph E.W. Earl after it was recently installed in the Oval Office. “I found it shocking,” says Kaphar. “It made me wonder—are there other people who recognize the other aspects of Andrew Jackson and are as uncomfortable with what feels like an incredibly ominous foreshadowing?”

Kaphar’s Shred of Truth slices the Jackson portrait into shreds, which are fanned out and nailed up to the gallery wall, exposing an emptiness underneath. To Naeem, the painting is an analogy for the Indian Removal Act of 1830, in which Jackson famously unleashed a government-authorized attack on Native Americans who resisted being pushed out of their homelands in the east. It “shows how Native Americans were shoved into different territories, cut into little strips of land that were apportioned to them,” says Naeem.

Ken Gonzales-Day’s approach is to extract lost or forgotten history.

The Los Angeles-based artist believes that for too long, both art and museums have created and reinforced racialized structures and notions. The objects displayed in museums—or in public parks and squares—help make his case, he says. “I’m looking for clues that there’s a history of this thing called race on this land we call America,” he says. The objects—sculptures, photos, other artworks—are traces of that history, says Gonzales-Day.

“Ken uses the camera as the main vehicle to really look at systems of representation,” says the show’s other curator, Taína Caragol, who specializes in Latino art and history at the Portrait Gallery. Gonzales-Day’s photographs give the viewer a “a look at how racial hierarchies are constructed,” she says.

Gonzales-Day, 51, says the conversation about race and history, “is very, very unhinged in our country. We don’t have any way of talking about it.” Art is a lever, a prod, a point of departure. Art is also a training mechanism, he says.

In his Profiled series, Gonzales-Day juxtaposes stark photos of classical sculptures and busts of white men and women with equally stark photos of sculptures of Native Americans, Africans and other persons of color. The sculptures tend to be shot in isolation, often with a black background. He’s showing how these representations have informed our view of race over the centuries. Fourteen of his Profiled photos are exhibited in Unseen.

“The profile, Gonzales-Day says, has long been used “for moral and character valuations.”

Gonzales-Day’s modus operandi is to dig behind the representations, thoroughly researching the provenance of existing art pieces, identifying those who perhaps did not have a name or a story, and giving them substance and context through his interpretations. For Profiled, he burrowed into museum collections around the world, including the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, the Getty Collection in Los Angeles, and the Smithsonian’s National Museum Natural History and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. In Profiled, his camera focuses our gaze on what we’ve perhaps always taken for granted.

“With these objects, we educated white people about who they were,” he says. And, it showed what they weren’t—dark, crude, blunt, heavy, plain, primitive.

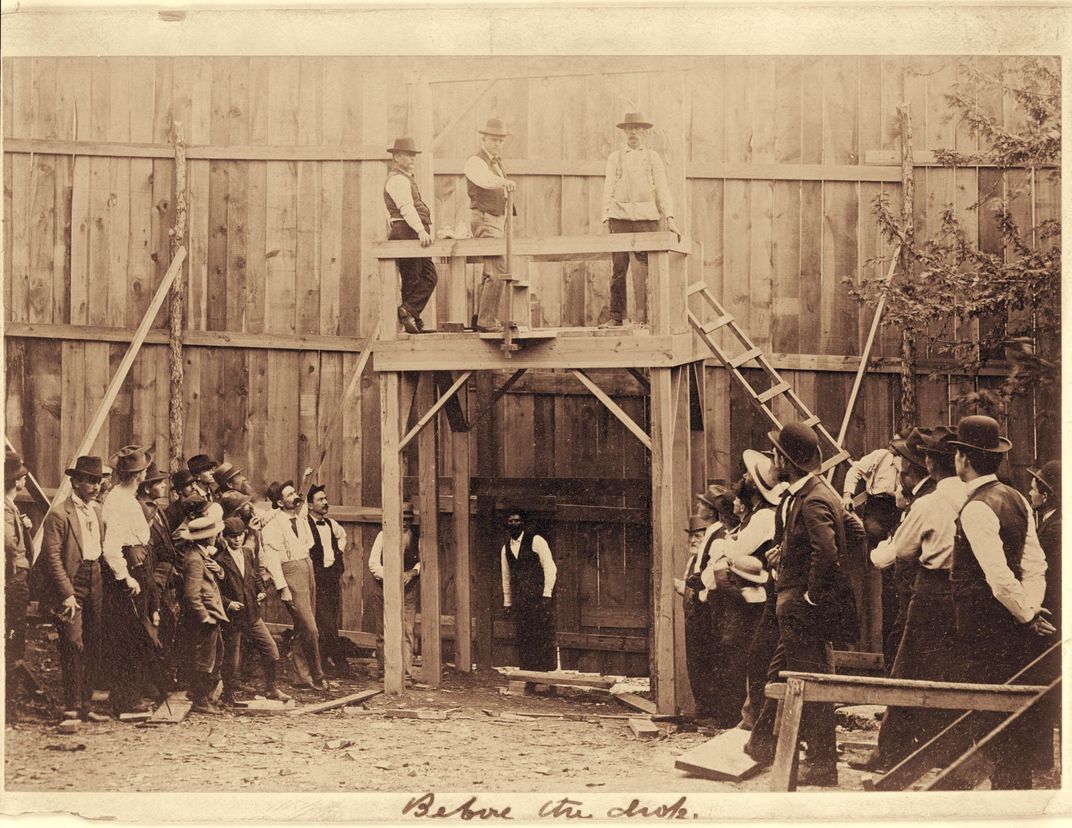

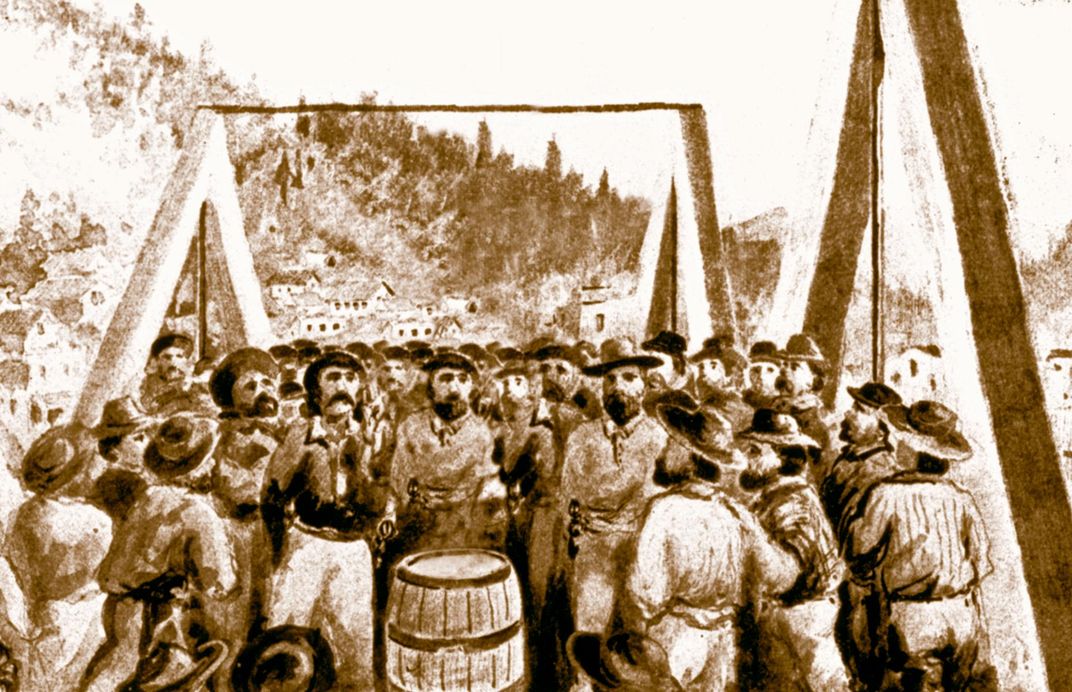

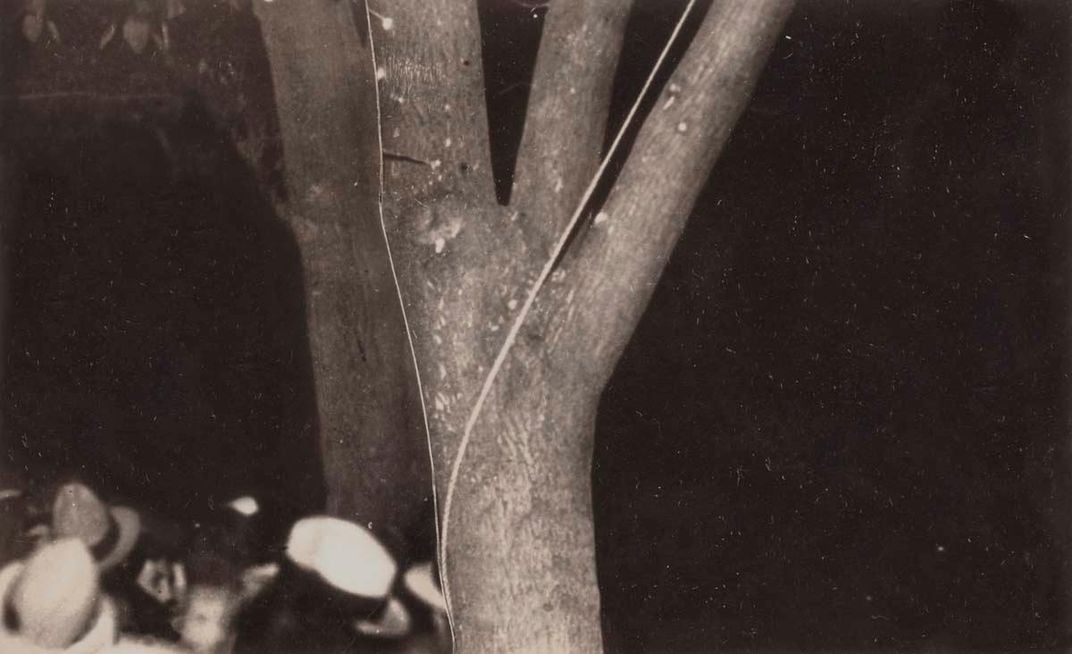

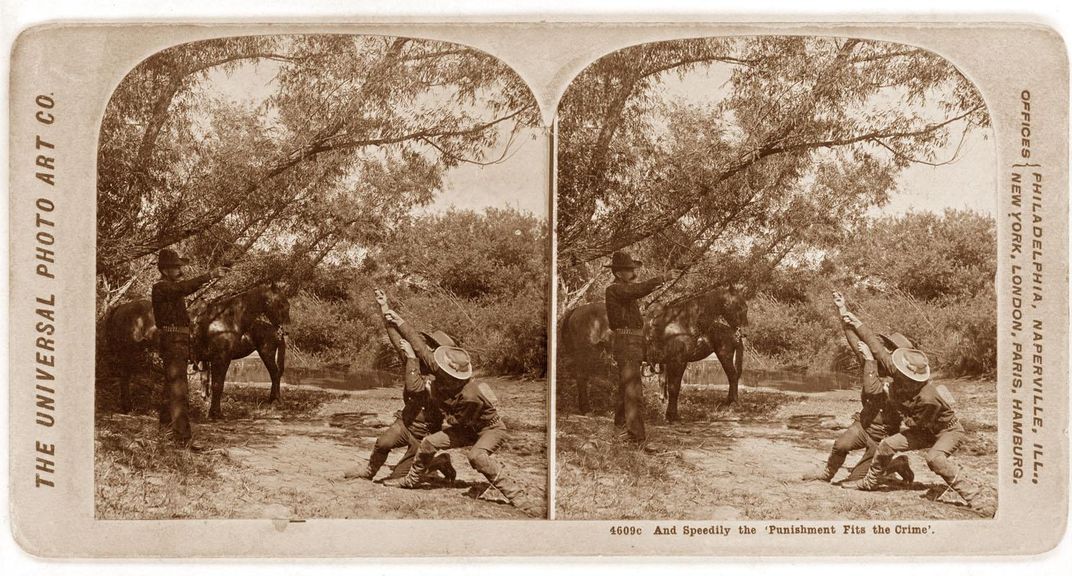

In his Erased Lynchings series, first exhibited in 2006, Gonzales-Day dug even deeper. It began with a dive into the history of racial violence in the West—and lynchings, in particular. He was moved to act in response to vigilante attacks on the Mexican border in the early 2000s. And he drew inspiration from the 2000 book, Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America, which compiled 100 photographs of lynchings of African-Americans in the South. Many were taken by professionals, and they were often circulated as “postcards” from the hangings. Without Sanctuary was a kind of reckoning—tallying the deaths, exposing the horror that a lynching could be a publicly celebrated event.

Gonzales-Day produced his own reality check—the 332-page Lynching in the West: 1850–1935. The book, published in 2006, established, for the first time, some 300 never-before documented hangings of primarily Latinos, but also Native Americans, Chinese and other non-whites—just in the state of California—between 1850 and 1935. Fifty had already been documented, but Gonzales-Day vastly expanded the knowledge of this particular racial violence.

“It creates another narrative that’s been virtually ignored or erased, says Eduardo Díaz, director of the Smithsonian Latino Center, who adds that exhibitions like this are crucial for artists of color. It lets them use their own voices to discuss their place in America, he adds. “It’s very important for us as a Latino community to have our people interpreting and contextualizing our history,” Díaz says.

For instance, when most Americans think about lynching, they “don’t think about ritualized murder that was perpetrated against Mexicans in California and Texas,” he says. It is an unknown, absent from history books. Much of the ugly violence—including lynchings—started after the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican War and stripped thousands of Mexicans of their nation and their land in an instant, says Díaz. Thus, began a long history of dispossession and institutionalized racism, which Gonzales-Day brings to the forefront, inviting the viewer to explore that forgotten history, he says.

Gonzales-Day was not satisfied having just written a book exposing that violence; his research also led to his Erased Lynchings photos. He accessed historical photos—in archives, museum collections, and through online auction sites—and re-photographed them.

He then digitally erased the hanging body. He didn’t want to “re-victimize the victims,” he says.

“I’m making the space visible for racialized violence,” says Gonzales-Day. “It allows people to consider the social conditions that made that possible in the first place,” he says.

In Disguised Bandit, originally taken around 1915, a group of uniformed men—presumably soldiers—stand under a barren tree in what looks to be high desert, staring at the camera seemingly without remorse. One young man holds a rope in his hand, which extends up over an upper branch. The words “Disguised Bandit” are etched into the bottom of the photo plate by the original photographer.

Gonzales-Day says he’s been unable to identify the soldiers. But they are clearly the focus of this photograph—not the absent lynching victim.When repeated in scene after scene, the effect is haunting. Gonzales-Day is painting a portrait of a white America eager to participate in violence against other races.

“How did that become an American past-time?” he asks. And, he wants Americans to ask themselves, “where would you be in the picture?”

"Unseen: Our Past in a New Light" is on view at the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. through January 6, 2019.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)