How an American Missionary Helped Capture the First Panda Given to the U.S.

“Missionaries sometimes have to tackle strange and unusual jobs,” David Graham wrote.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d5/64/d564b22f-9078-44ee-997d-1304787ef882/08_17_2014_panda_photo.jpg)

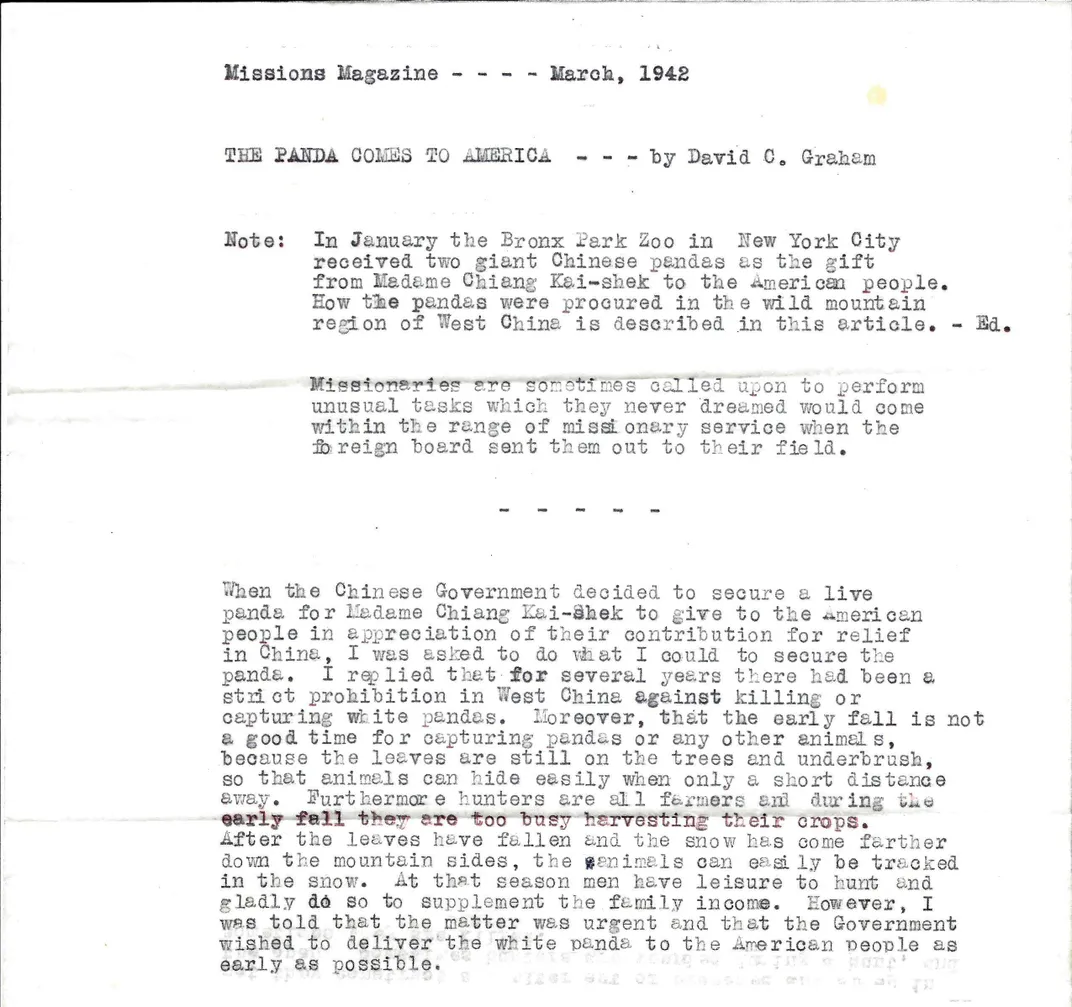

On November 9, 1941, in the midst of the Sino-Japanese conflict that would soon become a front in World War II, two pandas were handed over to John Tee-Van, a representative of the Bronx Zoo, in Chengtu, China. Four years before, Japan had launched a full-scale invasion of China, and America had given China some—rather limited—support. But as the Japanese offense had faltered, that support had mattered, and Soong May-ling, wife of nationalist Chinese President Chiang Kai-shek, saw “this chubby pair of comical black and white furry pandas" as a way to express the country's gratitude to America.

These two pandas, though, are little enough known that last month SmartNews erroneously identified Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing—the famous pair of pandas China sent to the U.S. following President Nixon's 1972 visit— as the first panda pair sent to the U.S. as a political gift. Fortunately, one reader let us know we'd missed this earlier bit of fascinating history.

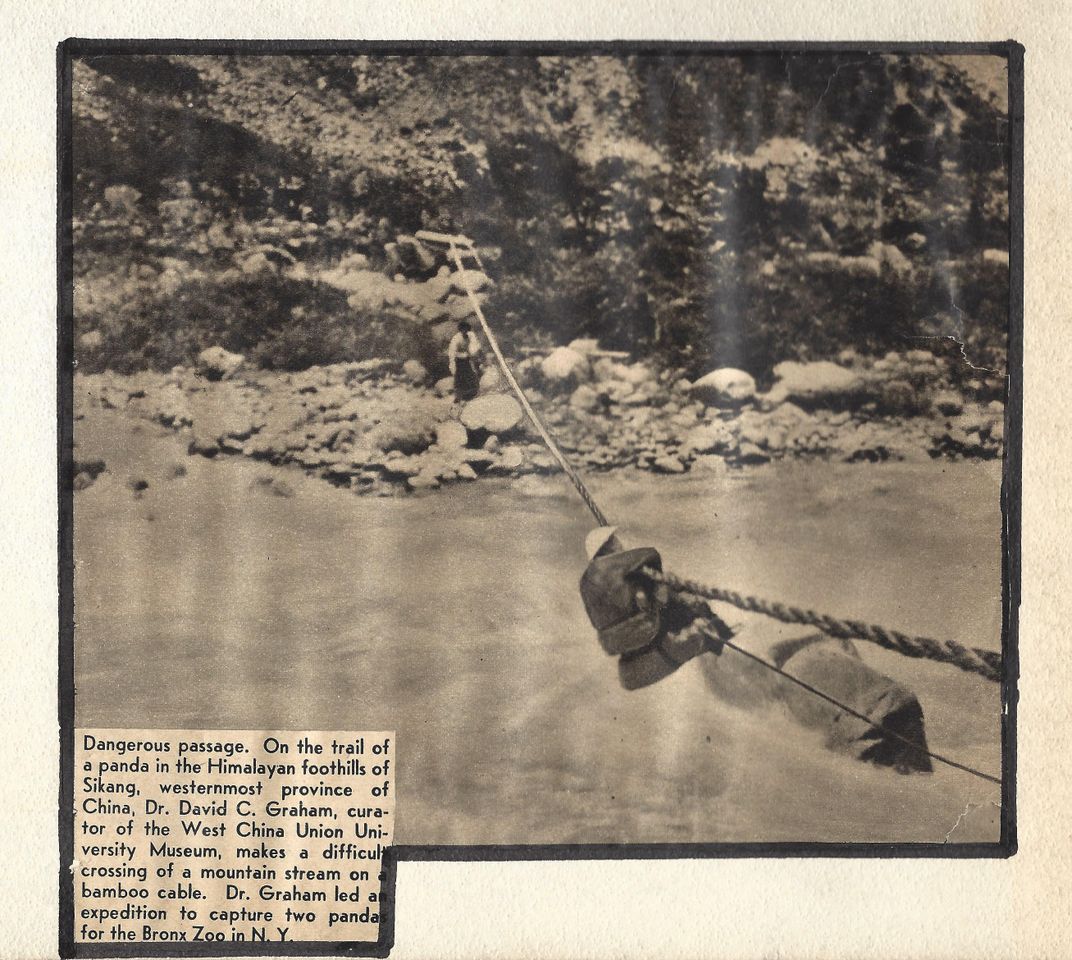

Michael Hoogendyk has good reason to know that, prior to Nixon's pair, another set of pandas had been given to the U.S. by Chinese officials. His grandfather, Dr. David Crockett Graham, was part of the team sent out into the Chinese wilderness to capture those first pandas. In the March, 1942, edition of Missions Magazine, Graham recounted his tale, which is reproduced in full below.

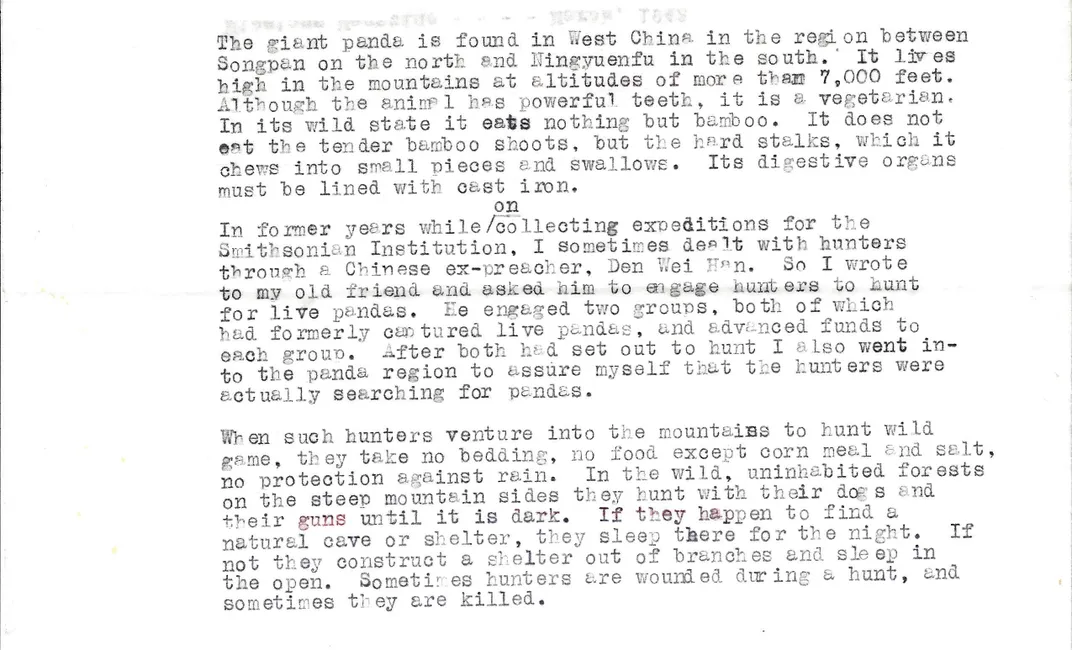

Born in 1884 in Green Forest, Arkansas, Dr. Graham was an ordained Baptist minister with a doctorate in Chinese religion. For nearly 40 years Graham worked in China's central Sichuan province, first as a missionary and later as the curator of the West China Union Museum. He was also an avid naturalist and over the years collected scores of specimens for the United States National Museum. In 1941, Graham was asked to assist in the task of capturing two live pandas—an endeavor that would eventually involved 70 hunters and 40 dogs, working in seven regions—"probably the biggest panda hunt ever organised at one time," Graham wrote.

Catching a panda was no easy feat. They live high in the mountains, where conditions can be tough, Graham wrote:

When [local] hunters venture into the mountains to hunt wild game, they take no bedding, no food except corn meal and salt, no protection against rain. In the wild, uninhabited forests on the steep mountain sides they hunt with their dogs and their guns until it is dark. If they happen to find a natural cave or shelter, they sleep there for the night. If not they construct a shelter out of branches and sleep in the open. Sometimes hunters are wounded during a hunt, and sometimes they are killed.

Even before reaching Ts'ao P'o, a center of the panda region, Graham and his friend Den Wei Han had to cross bridges made of bamboo cables—or, in one case, just a single cable:

Actually procuring a panda, though, was relatively easy: a local official had recently purchased one, and with a letter from a higher-up in hand, Den Wei Han was able to buy it from him. And while one panda would have been more than enough, returning to Chengtu, the capital of Sichuan province, Graham found that one of the other groups of hunters had already caught a second young panda.

The pandas' 35,000 mile journey to America was not uneventful. They were on a ship in the Pacific, headed to Hawaii, when the Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor. The ship, says the China Times, "began camouflage procedures to minimize the chance of an attack by Japanese aircraft, with the ship's chief officer reportedly threatening to camouflage the distinctively black and white Pan-dee and Pan-dah."

The pandas, though, made it to the Bronx Zoo—a symbol of a temporary international friendship and evidence that, as Graham wrote, "missionaries sometimes have to tackle strange and unusual jobs."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/smartnews-colin-schultz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/smartnews-colin-schultz-240.jpg)