How the Automobile Changed the World, for Better or Worse

New MoMA exhibition explores artists’ responses to the beauty, brutality and environmental devastation of cars and car culture

:focal(1019x809:1020x810)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/53/45/534505b2-e189-49f0-856e-63db9dd5e6df/rg-598a8311-2000x1333.jpg)

In the early 20th century, cars roared into society and revolutionized modern life. Automobiles and their attendant culture molded labor practices, the fight for civil rights, cities, the arts, social life and the environment in radical—and dangerous—ways.

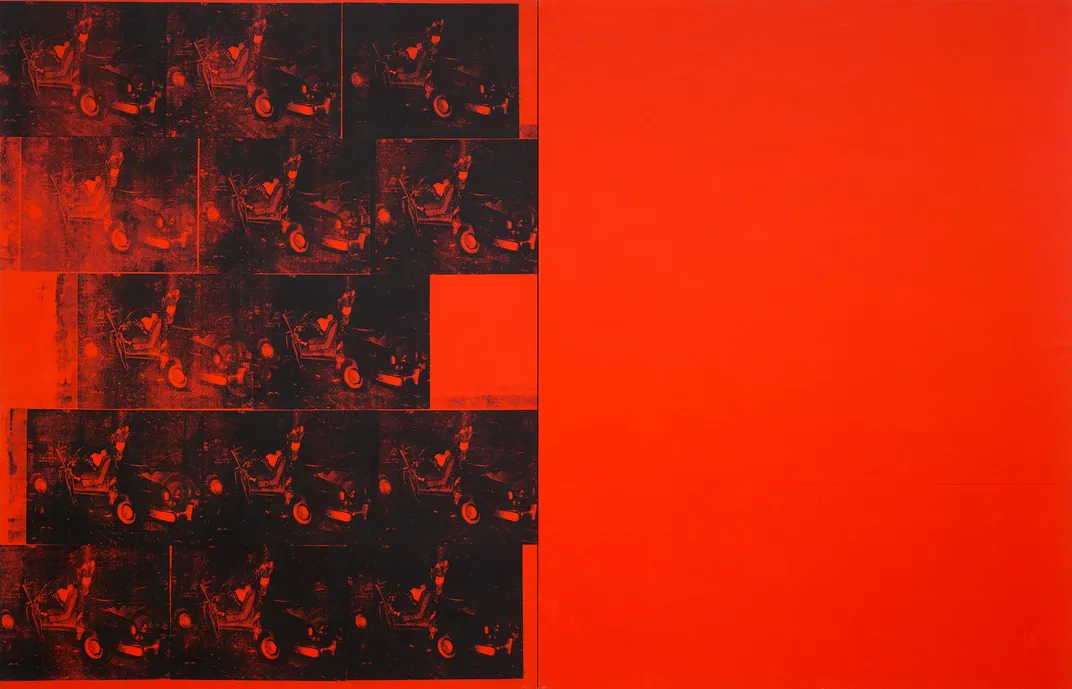

Artists who observed these changes responded with a range of emotions, from fervent admiration to horror. Now, “Automania”—a new exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City—takes readers on a ride through some of these responses, from an Andy Warhol silkscreen to Robert Frank photographs and a car hood painted by Judy Chicago.

As Lawrence Ulrich reports for the New York Times, the show takes its title from “Automania 2000,” an Oscar-nominated 1963 short animated by married British artists Joy Batchelor and John Halas. In the film, which art enthusiasts can watch online, a consumer craze for automobiles leads scientists to develop “40-foot supercars” that house families consigned to eating petroleum-based foods and ceaselessly watching television. Eventually, the crush of vehicles clogs roads, and the cars themselves spin out of control.

The bulk of the exhibition takes place on MoMA’s third floor. But viewers can also wander downstairs to the outdoor sculpture garden and peer into the windows of several exceptional car designs. Per a statement, nine cars from the museum’s permanent collection are stationed throughout the show, including a famed mint-green “Beetle” and a rare Cisitalia 202, a cherry-red 1946 racing car that owes it curved, seamless appearance to Italian workers who hammered its metal frame by hand.

Brett Berk of Vanity Fair notes that MoMA was among the first museums to treat cars as design objects, hosting the exhibition “8 Automobiles” in 1951. In the show’s catalog, then-curator Arthur Drexler made the (intentionally) provocative claim that automobiles were a kind of “hollow, rolling sculpture,” according to the Times.

Some artists found themselves enamored with the form and power of these new machines. In Italian futurist Giacomo Balla’s Speeding Automobile (1912), shards of white, black, red and green seem to explode out of the canvas in an abstract composition evocative of the energy of a race car.

Other artists reckoned with cars’ deadly potential. Today, crash injuries are estimated to be the eighth leading cause of death for people of all ages around the world. Pop artist Andy Warhol probed the routine horror of fatal crashes and their coverage in the media in Orange Car Crash Fourteen Times (1963), which reproduced the same newspaper image of a deadly collision on an enormous 9- by 14-foot canvas, as Peter Saenger reports for the Wall Street Journal.

Beyond the immediate bodily harm posed by vehicles, artists have also reckoned with their vast environmental cost. In a series of photocollages from the late 1960s, Venezuelan architect Jorge Rigamonti captured the dystopian industrial landscape of his home country, which is one of the biggest exporters of oil in the world. Pollutants also appear in an 1898 lithograph by French post-Impressionist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, which shows a male motorist speeding ahead, spewing a cloud of thick smoke over a nearby woman and dog.

Visitors unable to explore the exhibition in person can listen to online audio tours adapted for both adults and children. In one recording, Chicago—the groundbreaking artist who created The Dinner Party (1979) and ushered in a new wave of American feminist art—explains that her work in the exhibition, Flight Hood, was inspired by her time as the only woman in a 250-person auto body school. In 2011, she painted this car hood with a “nascent butterfly” form that references her first husband, who died in an automobile crash.

Cars and car culture have long been tied to Western notions of manliness and rugged individuality. By using a piece of metal so often associated with masculinity as her canvas, Chicago subverted expectations.

“This work is based on a series of paintings that my painting instructors hated,” she recalls in the clip. “… I understood, intuitively, that this imagery that my male painting teachers had rejected because it was so female centered, that there was something subversive about mounting it on the most masculine of forms—a car hood.”

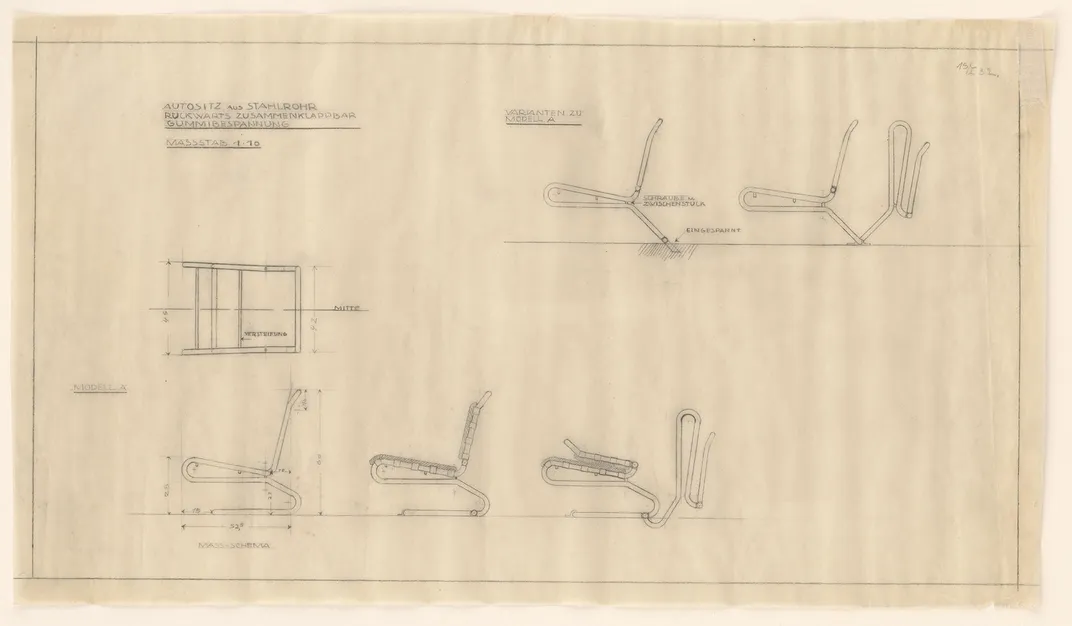

Lead curator Juliet Kinchin, who organized the exhibition with Paul Galloway and Andrew Gardner, also sought to emphasize women’s contributions to the male-dominated auto design industry. Relevant artifacts include textile artist Anni Albers’ upholstery materials and designer Lilly Reich’s 1930 sketches for a folding car seat.

“Women have actually been featured in these stories from the beginning,” Kinchin tells Vanity Fair. “That was something we wanted to tease out.”

All told, Galloway says that he hopes the exhibition pushes museumgoers to reconsider their relationships with their vehicles.

“This is absolutely a moment when we’re rethinking our history with things that we used to love and cherish,” he tells Vanity Fair, “and acknowledging that some of those things maybe were poisonous, or bad ideas, or death traps.”

“Automania” is on view at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City through January 2, 2022.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3e/1e/3e1e13ac-64e5-4db1-ba4b-9fe1ba1feaa1/1898_toulouse-lautrec_automoviledriver.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/89/67/8967bb16-a9ce-4c19-8a9f-9c69e47a35d0/dd_dsf4090-2000x1500.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9a/73/9a7322c3-bb3c-469a-bb68-bc118b85cda2/1947_havinden_takenochances.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)